July 23, 2020

A reimagined Monument Avenue could ‘reflect on our past and point our way to a more equitable future’

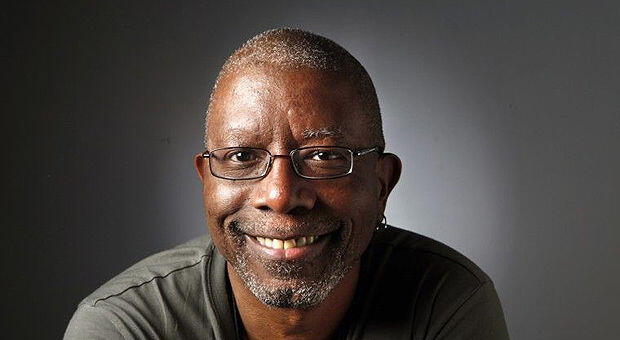

For Richmond Times-Dispatch columnist Michael Paul Williams, the idea that the monuments would one day be toppled once seemed implausible.

Share this story

The Confederate monuments along Monument Avenue were not merely symbols of white supremacy, they were designed to be part of a system to uphold white supremacy in Richmond, said Richmond Times-Dispatch columnist Michael Paul Williams on Wednesday in an online event hosted by the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“These monuments are not history. They cannot even accurately be called symbolic statements,” Williams said. “They were designed to be part of the actual infrastructure of white supremacy in Richmond.”

Williams’s talk, “Beyond the Monument: Crafting a Model for a Post-Racist Richmond,” was the second event in the Wilder School’s Alumni Lunch and Learn series, following an inaugural presentation in June that featured Secretary for Public Safety and Homeland Security Brian Moran discussing Virginia’s response to COVID-19.

Richmond’s monuments memorializing Confederate figures began in 1890, with the unveiling of the massive statue of Robert E. Lee and followed soon thereafter by the installation of others along Monument Avenue.

“Richmond has always been a place where Black lives and white lives were bisected by an interstate highway or by this tremendous gulf in wealth and power. This is all by design,” Williams said. “The Lee monument was erected in 1890 to assert white Southern dominance as part of what for decades would be part of an exclusively white real estate development.”

Real estate companies, he said, enticed white homebuyers with restrictive covenants that stated “no lots can ever be sold or rented in Monument Avenue Park to any person of African descent.” Williams quoted historian Kevin Levin, in his June article in The Atlantic, “Richmond’s Confederate Monuments Were Used to Sell a Segregated Neighborhood,” to provide context:

“The Confederate monuments dedicated throughout the South from 1880 to 1930 were never intended to be passive commemorations of a dead past; rather, they helped do the work of justifying segregation and relegating African Americans to second-class status. Monument Avenue was unique in this regard. While most monuments were added to public spaces such as courthouse squares, parks, and intersections, Monument Avenue was conceived as part of the initial plans for the development of the city’s West End neighborhood — a neighborhood that explicitly barred black Richmonders.”

Richmond went on to become a national leader in establishing racial zoning. After the U.S. Supreme Court found such policies to be unconstitutional in 1917, private and commercial discrimination continued in Richmond with covenants forbidding Black and Jewish people. When those deeds were outlawed in 1948, the city continued to embrace redlining policies that upheld segregation.

The city’s Confederate monuments, Williams said, can only be understood in this context: that they were part of a system upholding white dominance.

“The swollen overblown rhetoric that greeted the unveiling of the Lee monument and subsequent ones on Monument Avenue smacked of the desperation people employ when they’re trying to convince themselves and others of what they know to be a lie,” he said.

These monuments are not history. They cannot even accurately be called symbolic statements. They were designed to be part of the actual infrastructure of white supremacy in Richmond.

‘Those monuments fit this city’s prevailing racism like a hand in glove’

For Williams, who grew up in Richmond, the idea that the monuments would one day be toppled seemed implausible.

“Even after a monument to Arthur Ashe was added to Monument Avenue during the mid-1990s, a Black man was arrested on the avenue while walking home from work at St. Mary’s Hospital in the wee hours. He was hauled into court, where the judge asked, ‘Why didn’t you walk down Broad Street?’” Williams said. “I’m ashamed to say I accepted those monuments [for] too long, just as we have lived too long with our city’s glaring disparities. Those monuments fit this city’s prevailing racism like a hand in glove.”

Calls to remove the monuments grew after the 2015 murder of nine Black people in a Charleston, South Carolina, church by Dylann Roof, who had embraced Confederate symbols. Those calls intensified following the 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in support of Confederate monuments that resulted in the murder of Heather Heyer by a neo-Nazi.

Richmond formed a commission in June 2017 to consider what to do with Monument Avenue’s Confederate statues.

“In typical commission fashion, nothing happened, even with its recommendation to remove the Jefferson Davis statue. The focus in Richmond became addition rather than subtraction, with the arrival of a monument to Maggie Walker, the coronation of Arthur Ashe Boulevard, the dynamic addition of Kehinde Wiley’s ‘Rumors of War’ statue at [the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts], and talk of a monument on Monument Avenue dedicated to U.S. Colored Troops,” Williams said.

“In hindsight, they never would have been enough. The Confederates would always have had the other monuments outflanked, outsized, outnumbered.”

Renewed hope for Richmond

This summer, following the killing by police of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Black Lives Matter protesters in Richmond pulled down several monuments, including statues of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate Gen. Williams Carter Wickham, as well as the Howitzer monument on VCU’s Monroe Park Campus.

In early July, Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney ordered the removal of city-owned Confederate monuments immediately, starting with Stonewall Jackson and followed by those depicting Matthew Fontaine Maury, J.E.B. Stuart and others.

“Following the torture of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, Monument Avenue became a logical epicenter for the Black Lives Matter movement in Richmond,” Williams said. “I suspect the demonstrators realized that those monuments are the most obvious metaphor for the disparity between Black and white Richmond. Between Richmond and RVA. It’s a chasm that’s easy for anyone to see if they simply pay attention.”

The divide can be seen in how Richmond receives laudatory articles in The New York Times about its dining and culture, and articles in that same paper about how the city’s eviction rate is among the highest in the country, Williams said.

“Public policy has historically been weaponized against generations of Black Richmonders,” he said. “The schools have become a conduit to the criminal justice system. Our neighborhoods are gentrifying, changing the face of Richmond while leaving the city unaffordable to longtime residents. This makeover coincides with Richmond’s growth and growing wealth. There is no money in the pipeline to give public housing the makeover it needs.”

For generations, Richmond has failed to live up to its potential as a city, Williams said, focusing on preserving white supremacy rather than striving for a community that works for everyone.

“Just as monuments embody the Lost Cause, their toppling and removal has given us a renewed hope that Richmond can realize its long untapped potential, stunted by its embrace of a racist past,” he said. “Their removal represents a public disavowal of what they stand for and how they have come to define us. Getting there will not be easy. Amid this upheaval, coupled with the pandemic, I have never felt such a strange combination of stress, despair, hope and exhilaration. We are in the midst of what feels like, in Richmond, a second Reconstruction. Perhaps this one will be allowed to take, and not be cut off at the knees.”

For too long, he said, the city has “sought to define itself by a brazen boulevard dotted with monuments to white supremacy while rendering invisible thousands of people.”

“What would Richmond look like if every household had access to healthy food, a living wage, a decent affordable home in a safe neighborhood? Access to decent health care? Access to a laptop, the internet? And an education that will firmly place them on a ladder to success? A life unfettered by needless encounters with the police and criminal justice system? A city no longer defined by a white supremacist infrastructure, designed to keep its Black citizens in their place when they’re considered at all?” he said.

Williams said he has an “amorphous and unrealized vision for Monument Avenue,” one that “embodies justice, equality, unity and dreams nurtured and realized.”

“Just as its old statues were an homage to a lie and a guidepost for white supremacists and inequality, new ones can honestly reflect on our past and point our way to a more equitable future,” he said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.