Aug. 28, 2013

A tail of survival

Share this story

Since evolution first encouraged a fish to crawl from its aquatic home about 400 million years ago, land animals have faced the challenge of how to survive, adapt and thrive in dangerous terrestrial environments.

Similar to this early evolutionary step and familiar to science students and backyard biologists around the world, the tadpole-to-frog metamorphosis bridges the water-land divide every generation. When most froglets finally emerge from the water they’re no longer tadpoles, but they aren’t quite ready to be frogs either. This transition stage is particularly hazardous for the frogs because they have no perfect place to be. They are not a natural inhabitant of either water or land.

Back in the water, developing lungs require them to surface periodically to breathe, which draws dangerous attention. On land, their developing legs and remaining tail don’t allow for easy evasion of those higher links on the food chain.

So then, what is a young organism to do when it arrives on land as a half-developed frog with a tail and inability to jump, but finds itself in a foreign environment full of predators?

The answer, we know thanks to research published in the journal Oecologia in July, is absolutely nothing.

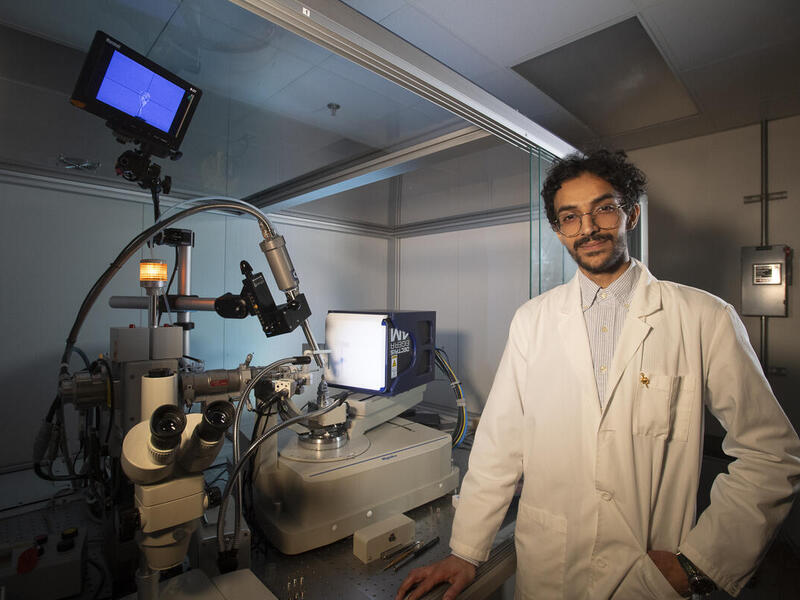

James Vonesh, Ph.D., associate professor in the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Biology, College of Humanities and Sciences, was co-primary investigator on the 2011 research team that found underdeveloped red-eyed tree frogs to be most resistant to predators when they simply stopped trying to get away.

“What this study shows is that when tadpoles develop arms and become more vulnerable in the water they reduce activity, but because they have to come to the surface to breathe or feed, that small reduction in activity doesn’t really help them out too much,” Vonesh said. “It’s better for them to clamber out (of the water), even though they have a long tail, because on land hunkering down works really well.”

On the team for this research were Karen Warkentin, Ph.D., Boston University, co-primary investigator with Vonesh on the grant for a larger project under which this investigation fell; Shane Abinette, an undergraduate VCU biology student; Randall Jiménez, an undergraduate student from Costa Rica; and Justin Touchon, Ph.D., Warkentin and Vonesh’s post-doctoral fellow.

Places like Panama are where new field biologists are made. ... You take an undergraduate who has an inkling of an interest in ecology and you bring them down to the Smithsonian Research Center in Panama and it’s like a candy shop, it’s a great place to see if this is really for them.

The National Science Foundation provided the grant, and the undergraduate students came on board thanks to a supplemental Research Experience for Undergraduate Programs (REU) award from the NSF.

Vonesh is particularly excited that undergraduate students had the opportunity to participate.

“Places like Panama are where new field biologists are made,” he said. “You take an undergraduate who has an inkling of an interest in ecology and you bring them down to the Smithsonian Research Center in Panama and it’s like a candy shop, it’s a great place to see if this is really for them.”

Considerable research explores how mortality risk based on size and habitat affects metamorphosis and how predators during metamorphosis are critical in natural selection, but Vonesh says something was still missing until his team’s research.

“In terms of how we think about metamorphosis in general – at least in the ecological literature – we typically think about it as something that is either focused on a switch point where it happens at some size or a key developmental stage, but behavior has been left out of the equation,” he said.

So, in Panama, the team examined behavior.

They looked at interactions between red-eyed treefrogs and aquatic predators (giant water bugs) and land predators (fishing spiders) across metamorphosis.

Tadpoles reduce activity as they develop forelimbs in the water, then reduce activity further when they emerge onto land. As they continue to develop on land, their tails become smaller and they begin to move more.

In the team’s aquatic trials, frog mortality increased when their arms emerged as hypothesized.

In their land trials, contrary to predictions, predation by the spiders increased as the tail was reabsorbed and the frogs began to move more.

“We expected – because previous literature focused on this being the tradeoff – the frogs that would clamber out would be more vulnerable to spiders because they have really long tails and they can’t jump very well,” Vonesh said. “But again, what this previous literature did not take into account is that the behavior of reducing activity – hunkering down – is very effective in the terrestrial environment.”

The findings, Vonesh says, open up a whole new line of questioning related to the extent behavior mediates metamorphic processes.

“We’ve shown here in this one frog that behavior is an important part of metamorphosis that has largely been ignored or overlooked,” he said. “So now it becomes a question of ‘how general is this that behavior as an important mediator of metamorphosis?’”

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.