Sept. 5, 2014

Engineering students mend medical equipment at hospitals in Nicaragua and Tanzania

Share this story

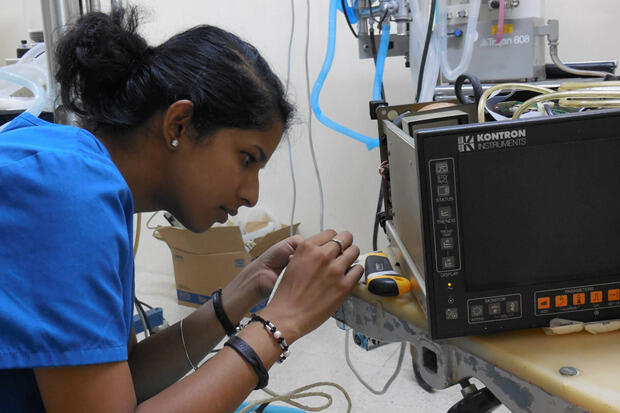

This summer, at a small, rural hospital outside of Estelí, Nicaragua, Virginia Commonwealth University student Shruthi Muralidharan encountered an aging electrocardiogram machine that was badly in need of repairs.

"A nurse let us watch as she used it while examining a patient," Muralidharan said. "She explained that it would work sometimes but that it was a little faulty — sometimes the electrodes had a weaker signal."

Muralidharan and a fellow volunteer, a student from Iowa University, opened up the machine and examined all of the connections. They discovered that one of the machine's leads had a severed point, which they quickly fixed by salvaging a replacement part off an old, unused ECG they found lying around.

The team also noticed that a lead that connects to a patient's chest was not staying attached. Muralidharan suggested that they might be able to fashion a makeshift connector by using an old blood-pressure cuff.

"We asked the [hospital's] maintenance guy, 'Do you have extra BP cuffs?' And he was, like, 'Oh yeah, I've got one.' He gave it to us, we cut it, superglued it, taped and put it on the electrode," Muralidharan said. "It was a little bit heavy, but it worked. We gave the ECG back to the nurse to use that day, and she told us it worked just fine and that it wasn't faulty anymore."

Muralidharan was one of three VCU students — all biomedical engineering majors in the School of Engineering — who spent two months this summer studying in developing countries and working in hospitals to help fix broken medical equipment.

The trip was part of VCU's chapter of Engineering World Health, a nonprofit organization that aims to improve health care in developing countries — Nicaragua, Tanzania and Rwanda — and to provide students with the opportunity to gain experience with industrial design, social entrepreneurship, business planning and global ethics.

VCU's Engineering World Health chapter, founded in 2013, was awarded the organization's "chapter of the year" award in May 2014. This summer's trips were financed by fundraisers held by the student chapter, contributions by VCU, and by the students themselves.

For the first month of the trip, the VCU students — along with a number of students from other universities — took classes and trained. Muralidharan and Brittany Allen, a junior biomedical engineering major, spent the first month in Granada, Nicaragua, taking Spanish and engineering courses, as well as working once a week in Granada Hospital.

"On Fridays, we'd always go to Granada Hospital," Muralidharan said. "A bunch of us would split off into different teams. I know some people worked on nebulizers, aspirators, air conditioning units — and just doing preventative maintenance. Working on motors, painting things, a lot of that kind of stuff."

For the second month, the students were sent to different cities and different countries.

Paul Howell, a senior biomedical engineering major, went to Tanzania, where he worked in the Meru District Hospital, fixing everything from oxygen concentrators to blood pressure machines.

"One notable accomplishment I was able to achieve was installing a brand new, yet unused — it had been sitting there collecting dust since February of this year — anesthesia machine," he said. "I was able to get it working, order the necessary additional parts and show them how to use it. After this, they were able to perform surgeries previously they had to refer to other hospitals."

Russell Jamison, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Department of Chemical and Life Sciences Engineering, is co-adviser of Engineering World Health at VCU with Christopher Lemmon, Ph.D., an assistant professor of biomedical engineering. Jamison visited the VCU students in Nicaragua and Tanzania over the summer.

"Two things stood out," Jamison said. "First, how utterly real this experience was for everyone involved, and, second, how devoted they were to the work they were doing."

Jamison called the trips a potentially transformative experience for engineering students.

"It is only when students understand the 'customer context' for the products they design that they can begin to make a difference in the developing world," he said. "The context must be experienced in order to be internalized. This is what I see happening with these students now that they have returned and begun to process what they saw."

Allen spent the second half of her trip in Jinotega, a small town in Northern Nicaragua. She and an Engineering World Health partner worked to repair damaged medical equipment and conduct preventative maintenance.

For one project, she was asked to fix a broken ventilator, a relatively expensive device that is essential in surgeries and in situations when patients are in critical condition. The hospital needed it fixed, and quickly, she said.

"Along with minor problems such as leaky valves and tubing, we found that the piston for the motor of the air compressor was not functioning properly and was preventing the machine from generating sufficient air power to inflate a patient's lung," she said. "We had to scavenge a working air compressor from an out-of-commission ventilator, fit it into our machine and replace all of the leaky tubing and valves."

"After all that," she added, "we were proud to return a fully functioning, newly calibrated ventilator to the doctors who had previously been using a very dangerous and unreliable device."

Allen said her time in Nicaragua was one of the best experiences of her life and broadened her understanding of health care and the world.

"I really enjoyed learning how to repair medical equipment and working in a hospital environment, but what made the trip so wonderful for me was the immersion in a whole new culture that I had known nothing about beforehand," she said. "The connections I made with my host families and with the technicians at the hospital are ones that I will always appreciate."

The trip also gave the students a chance to put their engineering skills to use in the real world, Muralidharan said.

"From everything you learn in class, you understand the concepts and you know you'll have to apply it sometime in your life. But I think that this was the first time where I was in a situation where you had to be resourceful and innovate and troubleshoot problems," she said. "You couldn't be scared to open up a machine and not know what's going on. I feel like this experience gave me more courage to take on problems head on."

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.