Feb. 26, 2016

From the archives: A window into the African-American experience at VCU and its predecessors

Share this story

While Black History Month has its roots in 1926, when historian Carter G. Woodson started Negro History Week, it first expanded to a month-long celebration on a college campus. Black United Students, a student organization at Kent State University, proposed the expansion and in 1970 was the first to celebrate Black History Month. In 1976, it was officially recognized by President Gerald R. Ford.

As colleges across the U.S. continue the tradition of paying tribute to the achievements and contributions of African-Americans this month, there is much to be learned from taking an introspective look at the African-American experience at Virginia Commonwealth University and its predecessor schools.

VCU Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives offer a wealth of information and resources on a wide range of topics, including an impressive amount of archival material chronicling the university’s history. Student newspapers, yearbooks, oral histories, books on the university’s history and other primary sources can be accessed anytime as part of VCU Libraries’ Digital Collections. The excerpts below relating to the African-American experience are just a small portion of the resources available in the collection, and the VCU community is encouraged to explore them to learn more at dig.library.vcu.edu.

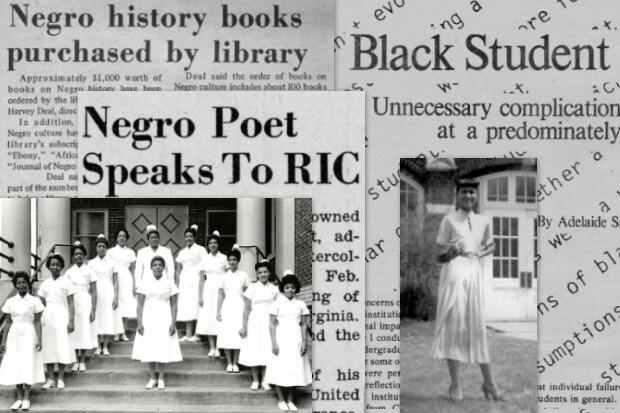

In 1938, The Atlas was the student newspaper of the Richmond Division of the College of William and Mary, which would later become the Richmond Professional Institute and eventually VCU. Black students were not accepted at the school at the time, although it appears there was an interest among students to learn about black culture.

“A.S.U. plans seminar on Negro history” from the Jan. 26, 1938, issue of The Atlas

A seminar on Negro history and culture will be presented by the American Student Union during the month of February. This program was suggested by the proposed “National History Week,” which was planned by the National Convention at Vassar College during the Christmas holidays.

For the first meeting of the month there will be a guest speaker; the second meeting will be devoted to special reports from the members, and group discussion. The actual and the economic history of the race, the art, music, and other phases of its culture will be discussed.

At the end of February, the Speech Choir of the State Teachers’ College at Petersburg will present a program under the direction of Dr. Cannon who started this group at the college.

RPI’s student newspaper in the 1940s was called Proscript. The following article details Langston Hughes’ 1947 visit to the Medical College of Virginia. Although MCV was not affiliated with RPI in the 1940s, students from both institutions, along with Virginia Union University, formed the Richmond Intercollegiate Council to bring black and white students together. Hughes was an established author and poet at the time and was known for being a leader of the Harlem Renaissance and writing about the black experience in America.

“Negro poet speaks to RIC” in Feb. 19, 1947, issue of Proscript

Langston Hughes, renowned Negro poet and playwright, addressed the Richmond Intercollegiate Council Wednesday, Feb. 12, at the Egyptian Building of the Medical College of Virginia. His topic was “Color Around the World.”

Hughes related many of his travel experiences in the United States, Africa, Russia, France, Italy, Germany and Sicily, and read several of his poems which were inspired by these ventures.

The speaker, after attending Columbia University for a year, rented a room in Harlem and attempted to secure a clerical job. He was unable to find one, however, and was forced to accept more menial “blind alley jobs.” His poem “Elevator Boy” was written during this time. Mr. Hughes disclosed that much of his poetry was produced during such periods of despair.

After this, Hughes secured employment on a ship bound for Africa. It was there that he was “surprised to discover the beauty and dignity of my own racial background.” Also in Africa and in European countries, the poet realized that racial prejudice exists outside the U.S. He is of the opinion that this discrimination was largely economic. Racial relations in Soviet Asia were compared before and after the last Russian revolution. The speaker hoped for a similar ending of racial intolerance in this country.

It was in Washington, D.C., during an unsuccessful attempt to enter Howard University, and in Paris that Hughes wrote many of his poems in syncopated rhythms. Illustrating this type of poetry, the writer read his “Negro Dancer” and “Out of Work.” The poet and playwright has more recently written the lyrics for the revival of “Street Scene,” a Broadway play.

Concluding Mr. Hughes paid tribute to the YWCA of America. It was under the auspices of the City Wide Industrial council of the Richmond YWCA that Hughes appeared before the local audience. He was introduced by Miss Adelle Pollard of the Council.

By 1969, RPI and MCV had merged to become VCU, and the Cabell Library had been designed but not constructed. The library was located in Ginter House’s former stable. While the first African-Americans were admitted to both of VCU’s predecessor schools in 1951, it wasn’t until 1969, the same year that the library made a significant purchase of books on black history, detailed below, that VCU began offering Afro-Americans Studies courses, thanks to the efforts of the African American Studies Committee.

“Negro history books purchased by library” in April 18, 1969, issue of Proscript

Approximately $1,000 worth of books on Negro history have been ordered by the library, according to N. Harvey Deal, director of libraries.

In addition, three periodicals on Negro culture have been added to the library’s subscription list. They are “Ebony,” “African Affairs,” and the “Journal of Negro History.”

Deal said the purchases are part of the number of volumes necessary to bring a library up to university status.

Deal said the order of books on Negro culture includes about 100 books which are reprints of 19th and 20th century volumes that are no longer available but are being reprinted by the New York Times.

These include things such as the “Diary of a Black Man,” Deal said. “Even getting these, we’re making a real beginning.”

Deal said the reason for making these purchases now is “because they haven’t been available before. March, 1969, is the release date of most of them.”

He said the Times is reissuing the books because of the same “popular demand” which is calling for the availability of them at university libraries across the country.

Although no representatives from Students for Afro-American Philosophy (SAAP) have visited Deal, the director of libraries said the order for volumes on Negro history was made after a SAAP delegation presented a petition to Dr. Francis J. Brooke, acting provost, last March 25, asking that Negro-oriented courses be incorporated into the curriculum.

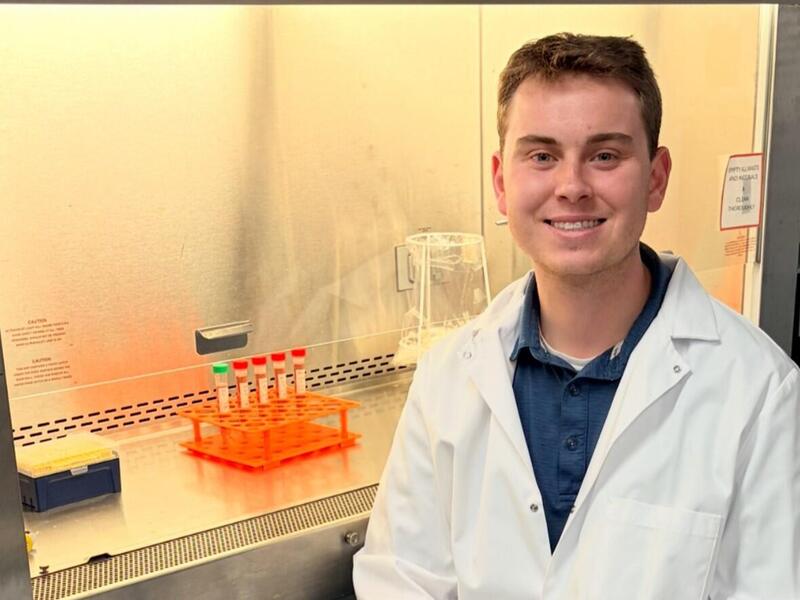

In 1920, MCV founded the St. Philip School of Nursing to train African-American women as nurses. The school closed in 1962, by which point the MCV School of Nursing had opened its doors to students of all races. The excerpt below is from a speech given by the dean of the MCV School of Nursing at a St. Philip School of Nursing reunion event in 1970.

Excerpt from speech by Dr. Doris B. Yingling, given at Fifth St. Philip School of Nursing Homecoming, July 3, 1970 (speech reprinted in its entirety in “A Historical Bulletin of the Saint Philip School of Nursing and Alumnae” in 1978):

Many of you may be wondering what the Saint Philip School of Nursing had, if anything, to do with the present programs of the School of Nursing at MCV and/or the new University. I feel that a great deal was contributed by this very important school. First, there has been provided an opportunity for Negro students to enroll in the Medical College of Virginia baccalaureate program. Some of you will recall that as far back as 1954 there were Negro students enrolled in the baccalaureate program. Since that time we have had a number of Negro students enrolled. While the number has been small, and we wish to improve this, the quality of student has been high; and we have been pleased with contributions these nurses are making. This fall, Mrs. Vashti Richardson, Saint Philip Alumna, will join our faculty in the Department of Community Health Nursing. She will be the first Negro member of our faculty, and we are most pleased about these prospects and the help she can give us in so many ways.

The graduates of the Saint Philip School of Nursing who have remained at the Medical College of Virginia in nursing positions deserve special commendation for their loyalty and support to the institution. During recent years, like most large medical centers, we have experienced problems in adequate staffing for patient care. Contributions of the graduates of the Saint Philip School of Nursing have been many and significant, and we recognize this and commend each of them for it. It would be impossible to mention all by name, and I wouldn’t dare begin because I am certain I would miss someone quite valuable. Most of you know who these persons are, and I can assure you that they have maintained the reputation of the Saint Philip School of Nursing and its ability to produce good nurses to the “nth” degree.

What can you do to be of more assistance to the MCV School of Nursing, the MCV Hospitals, and Virginia Commonwealth University? Perhaps one of the most important things would be to help us recruit more qualified Negro students. While we have worked at this, we have not succeeded to the extent I believe we could and should. We are very anxious to have well qualified students of all races, and I believe we can offer young persons of your race a fine opportunity. Perhaps a liaison committee to work with us would be of value in ascertaining ways we might further activate this recruitment.

Originally produced by VCU’s Black Student Alliance and the student branch of the League of Black Journalists, Reflections in Ink was a student newspaper that gave African-American students a voice at the university. Published from 1978 to 1994, its logo was “To be unaware is to be nowhere.”

Excerpt from “Black Student Experiences: Unnecessary Complications Black Students Endure at a Predominately White Institution” by Adelaide Simpson in the spring 1979 issue of Reflections in Ink

What are some of the concerns of black students at a predominately white institution? What is the psychological and emotional impact of their experience? Early this semester I conducted a number of interviews with black undergraduate and graduate students at VCU to explore some of their experiences here…

In the taped conversations I had with black males and females, a number of themes emerged. Each individual was quite different with respect to personality style and background. However, most felt added pressures and frustrations that relate to being black. Frequently there were expressions relating to proving oneself, to convincing classmates and professors of one’s competency. Perhaps part of being black in a white institution is overcoming stereotypes of inferiority and proving that one is just as capable as one’s white counterparts. It may be true that most students feel a pressure to compete and prove competency, but there is an added burden for black students to combat stereotypes. The pressure is also intensified by ethnic identity and feelings that individual failure harms the status of minority students in general.

Feelings of alienation and lack of acceptance were also expressed. A few students stated feeling less comfortable in classes or departments where there were no other or very few blacks. As one female medical student explained, it takes an extra effort to assert oneself and to be accepted by white peers and faculty. She also mentioned instances of being ignored. For example, when an instructor never looks at you and looks at or responds only to the persons on either side of you, then you know you’re being ignored. Her approach to dealing with being ignored was to assert herself verbally and to make herself known through presenting correct information. Some of the men felt that they were so frequently put down that they sometimes withheld from participating in class. The men particularly felt that their responses were challenged more and accepted less than those of other students. One man even mentioned that some students were reluctant to accept blacks in a leadership role in small group sessions.

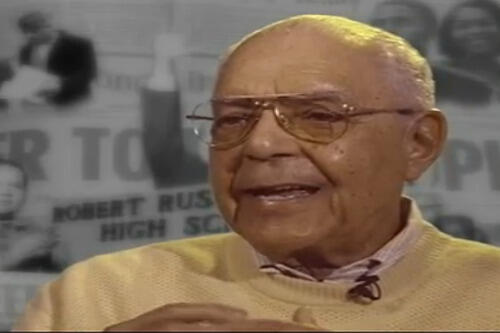

W. Ferguson Reid, M.D., was a Howard University-trained surgeon and the first African-American elected to the Virginia General Assembly since Reconstruction. In 2003 he was interviewed for the Voices of Freedom project, a collection of videotaped oral histories produced by the Virginia Civil Rights Movement Video Initiative. In the excerpt below, he discusses how segregation affected his educational experiences.

Excerpt from W. Ferguson Reid transcript, 2003; part of the Voices of Freedom oral history project

CARRINGTON: What were some of your first experiences with segregation?

[E]ven though the Medical College was within walking distance of my house, I had to go up to Washington.

REID: Well, we always knew that there are certain things you could do and certain things you could not do. We always knew that you couldn’t drink out of a white fountain, you couldn’t go into a bathroom that was marked white. You couldn’t eat out at a lunch counter. You couldn’t try on clothes in department stores. You couldn’t eat lunch in a department store even though lunch was available to everybody else. If you ate it, you had to carry it out. You couldn’t sit down at the counter. You couldn’t go to Miller & Rhodes Tea Room, or the Thalhimer’s room that they had for people to relax in. Also, as far as education was concerned, there were obstacles there. We had to go to segregated schools. There were no black principals at that time. All of the principals were white. There was a glass ceiling for the teachers and principals. There were different pay scales. Men, white, got more money than the female white teachers, and the black male teachers got less money than the white female teachers and the black female teachers got less money, so there was a standard of segregation all up the line. These were some of the obstacles. After I finished Virginia Union, I knew that I couldn’t apply to the Medical College of Virginia because that had not been broken down, and even though the Medical College was within walking distance of my house, I had to go up to Washington. I said I was bussed to Washington to keep from going to medical school here close to my home, which was an extra expense that my family had to pay for room and board in addition to, you know, the tuition so that was a handicap along that line.

Grace Harris, Ph.D., retired earlier this year from VCU, where she served as dean of the School of Social Work, provost and acting president during her 48-year tenure. She received her master’s in social work from RPI in 1960, although she was originally denied admission because of her race when she first applied to the school in 1954. In 1999, the VCU Grace E. Harris Leadership Institute was established in her name. Harris participated in the VCU Oral History project produced by VCU Libraries in the mid-2000s to capture the stories of prominent individuals with strong connections to the university.

Excerpt from Grace Harris interview transcript, 2007; part of the VCU Oral History project

BETSY BRINSON (interviewer): Well I’m coming to the end of my questions here but I just wondered if there’s anything that we haven’t talked about that you think is important to add to this interview?

GRACE HARRIS: Well one thing that I had talked about and I had mentioned to Kathy that an important part of the years I was in the School of Social Work were my efforts around the whole question (pause) of where black people, where African American people, fit in our society and some of the very blatant segregation and discrimination we faced. More discrimination than segregation, I guess, but some of it was segregation in the early years. Some of the efforts during that period focused on these issues and how to bring about change. I think back to the years when I first came to the university in the School of Social Work and the extent of discrimination in statewide meetings for example. If we were going to a conference in Roanoke, Virginia, we’d have to live in a home of black people in the community, not able to go to the Hotel Roanoke. And how I organized some groups to say, “If we cannot meet together as social workers, in the state of Virginia, then we should not go to the Hotel Roanoke.” So over time we had an impact on making that happen. So, my point is that I took a leadership role in an effort to bring about change in regard to race relations. It was something that I was very involved in and it felt good that we were able to bring about some changes.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.