Sept. 29, 2016

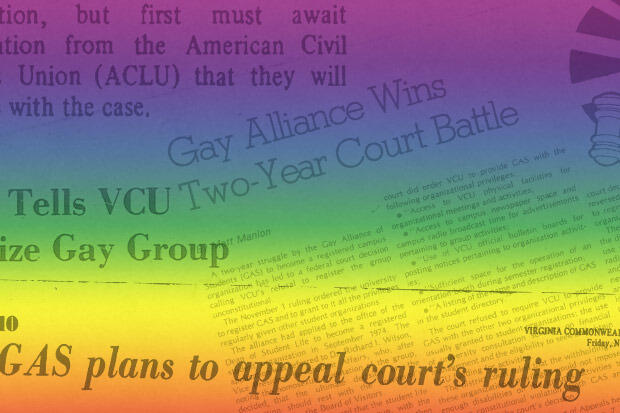

Inside the fight to win VCU’s official recognition of the university’s first LGBTQIA student organization

Share this story

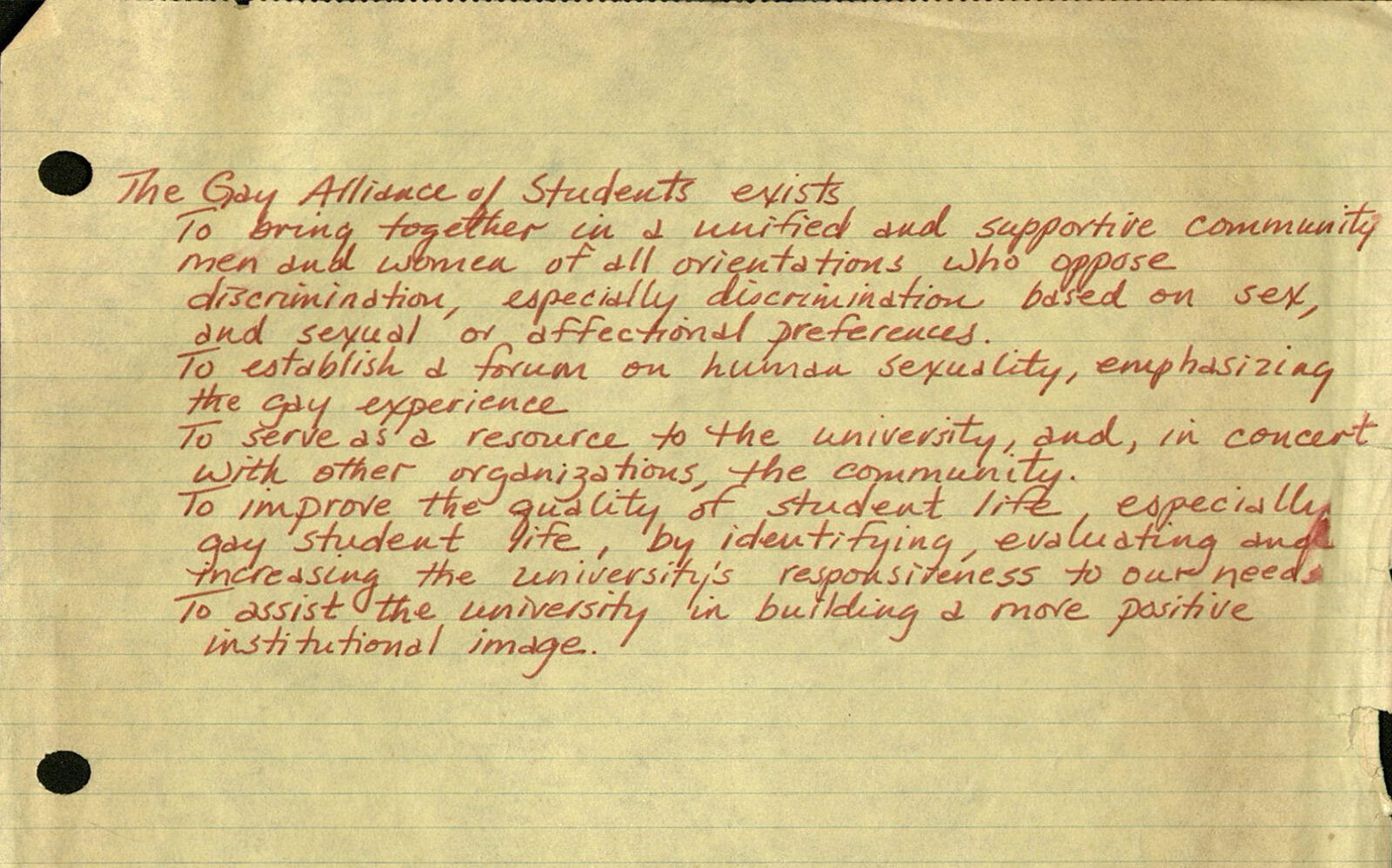

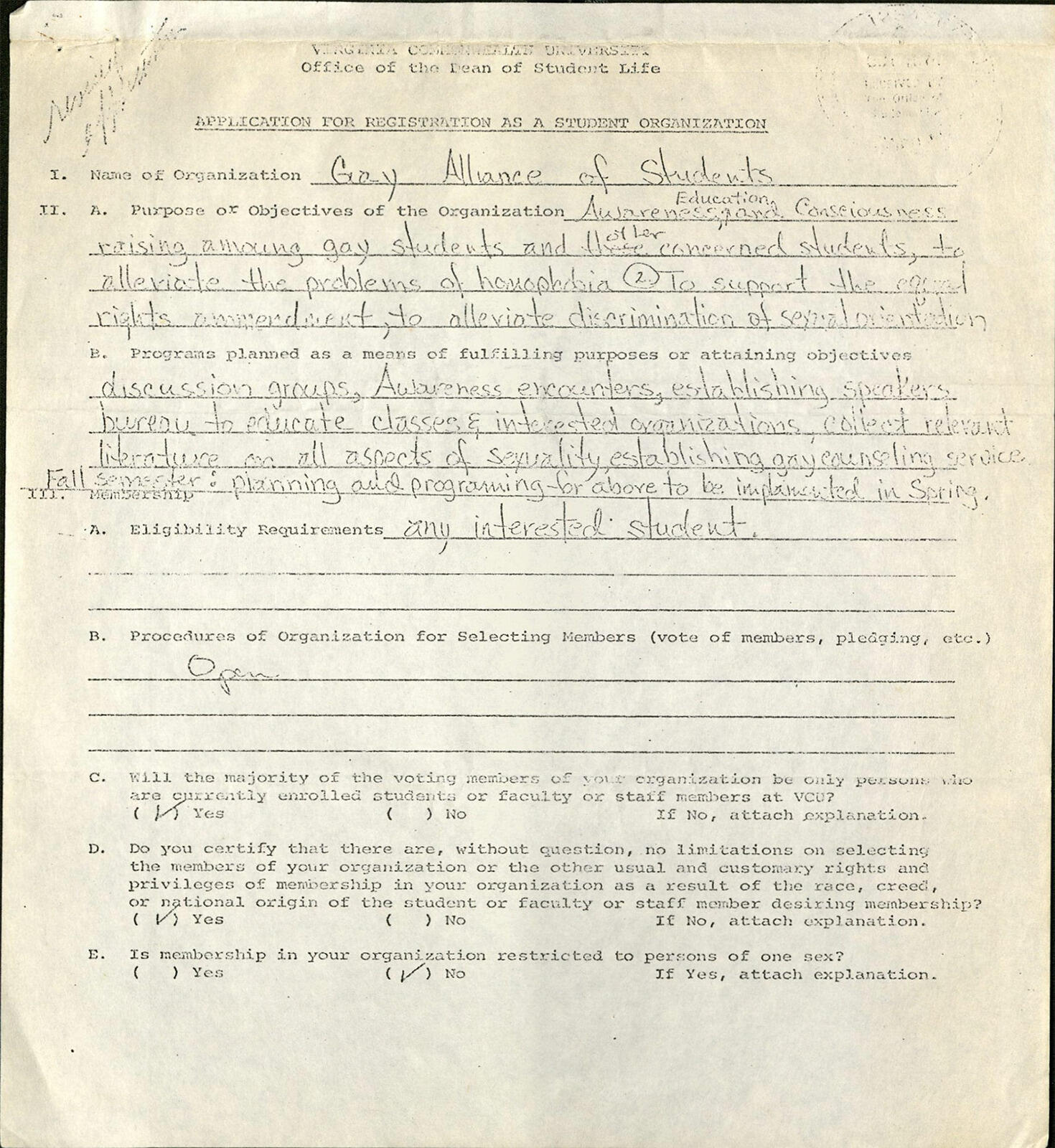

In the fall of 1974, a group of gay, lesbian, bisexual, questioning and straight Virginia Commonwealth University students founded the school’s first LGBTQIA student organization, the Gay Alliance of Students, with the goals of “awareness, education and consciousness-raising among gay students and other concerned students, to alleviate the problems of homophobia, to support the Equal Rights Amendment [and] to alleviate discrimination of sexual orientation.”

Source: The VCU Gay Alliance of Students Collection, 1974-1976, a collection in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library

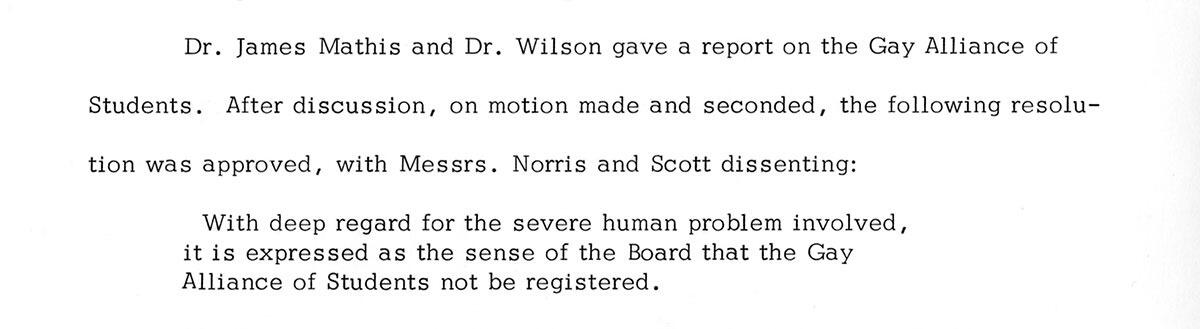

But when the group filed an application to be recognized as an official VCU student organization — thereby allowing it to use campus meeting spaces, advertise on university bulletin boards and in student media, and be included in a student organization directory — things didn’t go as planned. The application was not processed in the usual manner. Instead, the vice president for student affairs sent it to VCU’s Board of Visitors, which promptly voted to reject it.

“With deep regard for the severe human problem involved,” the BOV moved on Oct. 17, 1974, “it is expressed as the sense of the Board that the Gay Alliance of Students not be registered.”

Surprised, but by no means ready to give up, the students enlisted the help of the American Civil Liberties Union and filed a federal lawsuit against VCU officials and the BOV, alleging violations of their constitutional rights of freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

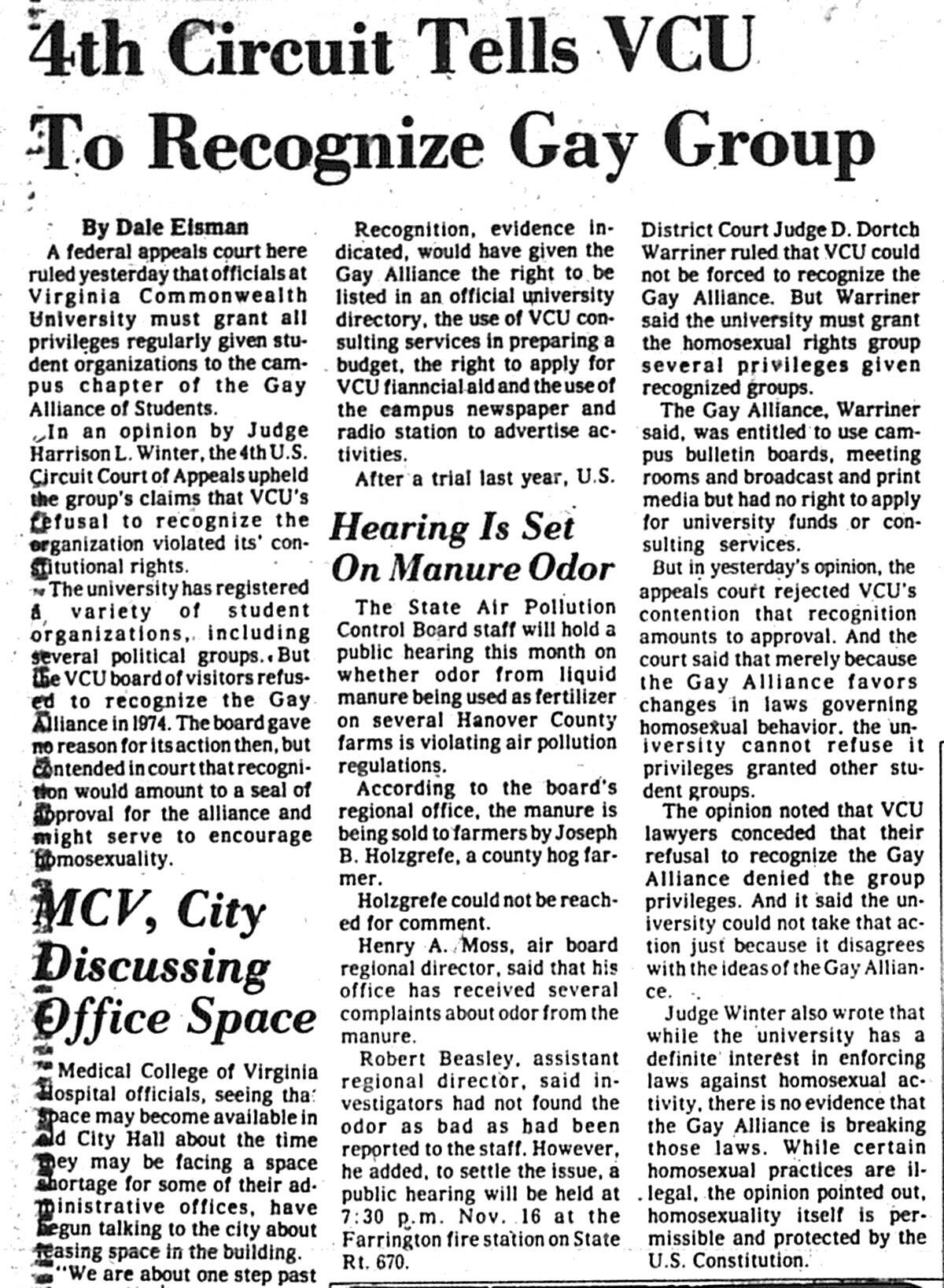

A two-year legal battle ensued, and the Gay Alliance of Students ultimately prevailed. In October 1976, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit in Richmond handed down an opinion that forced VCU to officially recognize the group, and to allow it to apply for funding and space allocations just like any other VCU student organization.

What’s more, the decision applied not only to VCU, but also colleges and universities across Virginia, as well as every other state in the appellate court’s jurisdiction, including Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia.

At noon on Tuesday, Oct. 4, several VCU alumni involved in the fight to win VCU’s official recognition of the Gay Alliance of Students will take part in a panel discussion, “Trials and Triumphs, 1974-76: The Struggle for Recognition of VCU’s first Gay Student Group.” The event is free and open to the public. It is part of a fall speaker series titled “Celebrating Forty Years of LGBTQIA Activism at VCU,” which is organized by the Humanities Research Center in the College of Humanities and Sciences.

As a preview of their talk, several members and allies of the Gay Alliance of Students shared their memories.

How did the Gay Alliance of Students come about?

Dottie Cirelli: In the early ’70s, VCU was having a week of seminars on human sexuality. I was in graduate school at VCU in [psychology], and completing my practicum at the counseling center. I learned there were no sessions being offered on homosexuality. As part of my coming out, I wrote a research paper and passed it out to the staff at the counseling center.

It was a background on all of the theories on homosexuality. There was a noted psychiatrist at the time, a Freudian, [Charles] Socarides, who claimed that homosexuality was aberrant behavior, a sign of arrested development or mental illness. But there was also research by Evelyn Hooker, a psychologist who had just completed a research project where she administered psychological tests to two groups — gay and straight — and found no difference between the two groups.

That research was one of the first forays into the understanding that homosexuality is normal – it’s not an aberration, it’s not a personality disorder, and that gay people are just as well adjusted as anybody else.

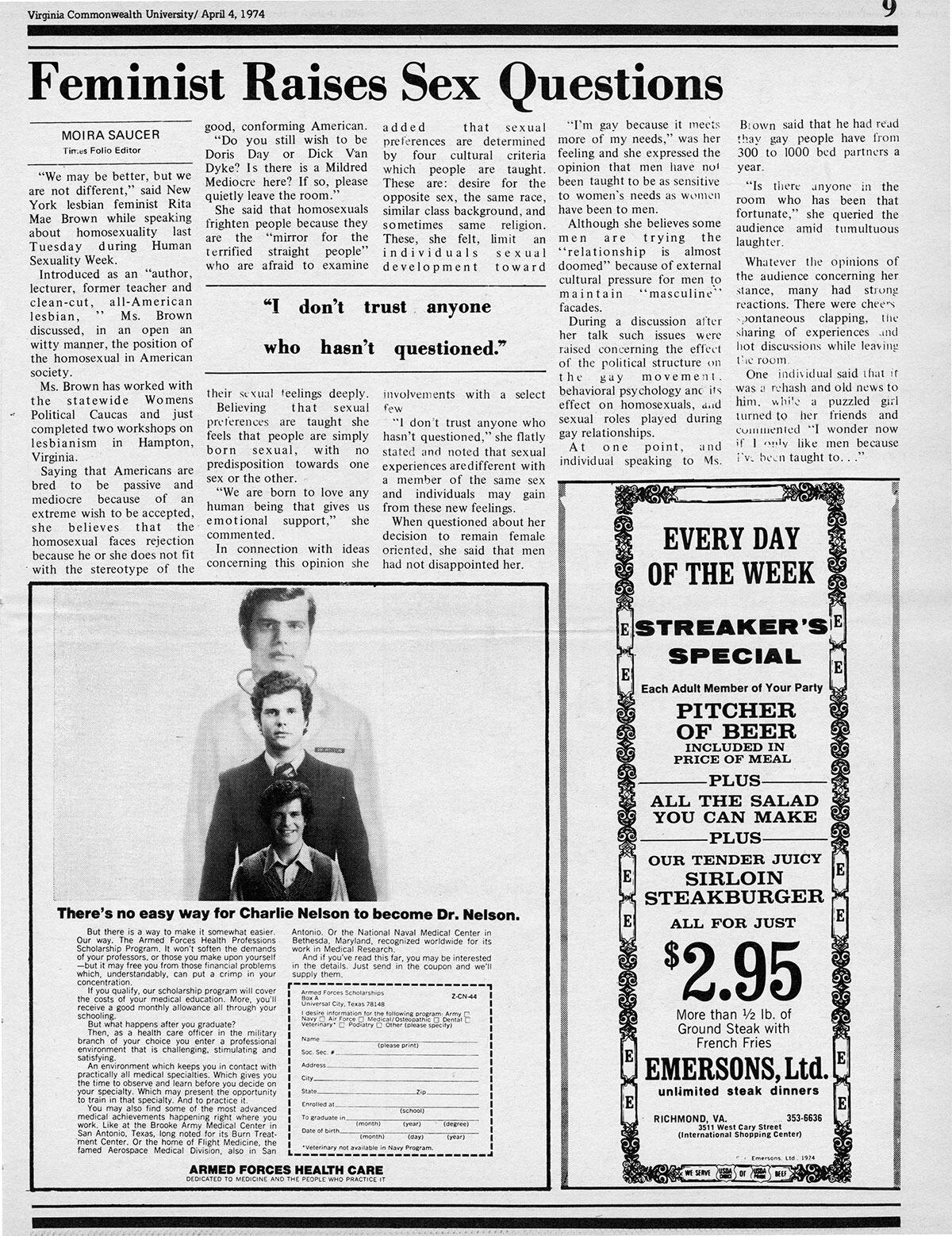

The Commonwealth Times, April 4, 1974

Source: VCU Libraries' Commonwealth Times Digital Collection

That research gave me the courage to approach the VCU administration to include homosexuality as a seminar topic. Stephen Lenton and Steve Furman, who were [administrators in] University Student Life at the time, were supportive and Stephen, in particular, championed the idea. The session was added to the schedule.

Also, at the time, Rita Mae Brown had just published her book, “Rubyfruit Jungle” [a coming-of-age novel about growing up as a lesbian in America]. A friend of mine, Frances Stewart, also in grad school, read the book and gave it rave reviews. So, I invited Rita Mae Brown to come to campus and give a keynote at the homosexuality session. She accepted! She gave a great motivational speech about being gay and the need to come out and fight for our rights.

At the end of her speech, I passed around a sheet of paper and asked if anyone wanted to sign up to start a gay student group. We started meeting in a church downtown.

It was the first time that gays on campus had a place to come together and talk about how they were being treated in the classroom, or, if they had jobs, how they were being treated at work. And also, of course, [the] Stonewall [riots by the LGBTQIA community in New York City in 1969] was a real catalyst for people to say, “We deserve to be treated just like everybody else.”

Brenda Kriegel: I was in the process of coming out at the time, and there was a group of us who wanted a place [where we could talk to each other], and we were looking for places other than the local bar scene.

At the time, there was a community group — I think it was called GAP [Gay Awareness in Perspective] — in the Richmond area, and it was basically a discussion group and had speakers and things like that. Then, there were some students — like Dottie Cirelli and myself — who thought, “Why can’t we have something like this on campus for just students?”

So I think it was sort of a loosely discussed possibility, and [Assistant Dean of Student Life] Stephen [Lenton] said, “If you get this together, I’ll agree to sponsor it.”

So, somehow or other, [the Gay Alliance of Students] came to fruition. We didn’t think it would be well-received, but we wanted to have a place to meet to deal with both internal and external homophobia. I think that is why we named the GAS. I can remember a lot of discussion as to what to call the group.

Source: The VCU Gay Alliance of Students Collection, 1974-1976, a collection in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library

What led to the BOV rejecting the Gay Alliance of Students’ request to become officially recognized as a student organization?

Walter Foery: The group formed in September of ’74. I didn’t come along until January of ’75. So they were doing whatever they were doing for almost five months before I came along.

On the 16th of September, 1974 — and don’t think I remember these dates, I’ve got them written down in front of me — William Duvall, who was associate dean of student life at the time, sent GAS a letter because he had received our application for GAS to become a student group, and he [was asking] for some clarification.

The group submitted an amended application in early October of ’74, and the VCU Board of Visitors said no to that on the 17th of October ’74.

Now there’s a couple things that were noteworthy about this. First of all, when the Board of Visitors first saw this item on their agenda, they thought, I’m sure, “What the hell’s this?” They had never before dealt with a student group application. In fact, the number I remember was 144 — I can’t swear that that’s accurate — but I’ve always remembered there were 144 VCU student groups ahead of us that were formed with no problem. “You want to be the chess club? OK, you’re the chess club. You want to be Future Farmers of America? OK, you’re that.” One hundred forty-four times, a group of students got together and said “We want to form an organization,” the university said, “Fine.” We were the 145th, and University Student Life didn’t act on it. They passed it on to the Board of Visitors, because — I’m assuming — they were afraid.

And so they decided, no, we could not form a student group.

One hundred forty-four times, a group of students got together and said “We want to form an organization,” the university said, “Fine.” We were the 145th, and University Student Life didn’t act on it. They passed it on to the Board of Visitors, because — I’m assuming — they were afraid.

The [BOV’s] letter was sent to the group in October of ’74 and our feeling was, “What the hell do you mean, ‘no?’” What about freedom of speech and freedom of association? Even in those times, it was something of a surprise. We weren’t asking for anything other than to be able to sit down in a room and talk about stuff.

Source: The VCU Gay Alliance of Students Collection, 1974-1976, a collection in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library

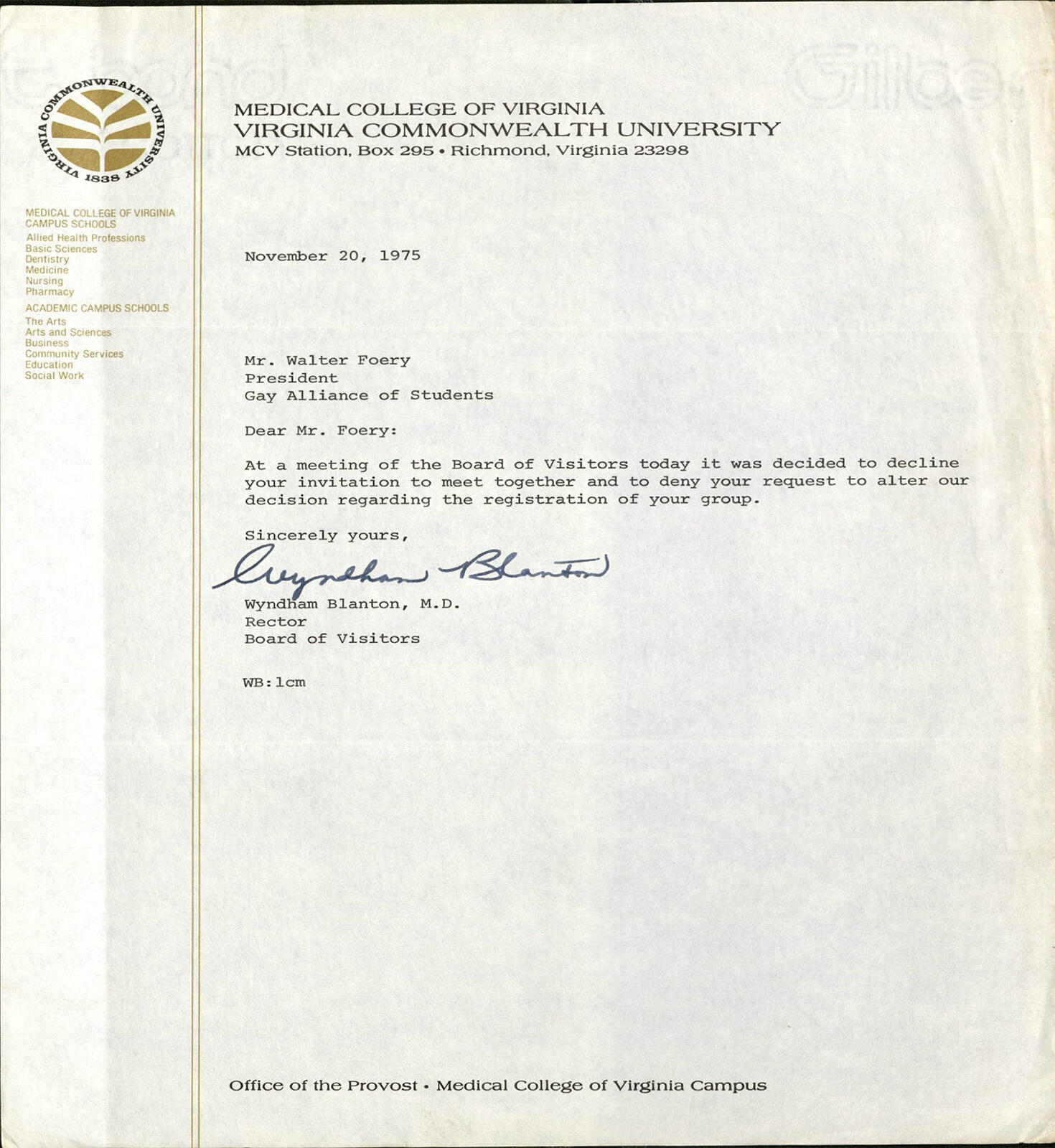

Another favorite memory is that by the time I came along, I wrote a letter to the board [of visitors], asking them to reconsider their decision and asking for a chance to meet with them to talk about it. They wrote back a one-sentence letter that basically said: No and no. “We will not reconsider and we will not meet with you.” I remember being stunned. I felt like I was dealing with a 12-year-old saying, “It’s my ball and you can’t play with it and I’m leaving.”

They wouldn’t reconsider and they wouldn’t even talk to us to hear our case. We thought, “This can’t be.” It was pretty unanimous that we needed to do something, and the something to do was obviously file a lawsuit.

Kriegel: They basically told us, we can’t recognize you because the outside community would not be too pleased, and that [supporting gay and lesbian students] was not an acceptable thing in the capital of the South. Those weren’t their words, those are my words. But it was controversial in nature, and [they thought it would] not go over big among the powers that be in Richmond.

What was the feeling on campus at the time? Was it generally supportive of the Gay Alliance of Students?

Foery: Well, I was not a typical student. First of all, I was a little bit older. In ’74, I would have been 26. And I didn’t live on campus. So it’s not like I left class or a Gay Alliance of Students meeting and went back to the dorm.

So I was kind of at class or, if I wasn’t at class, I wasn’t really on campus. So it’s kind of hard for me to answer that question.

I can tell you one thing sticks in my mind. Of the papers that I donated to VCU, one was a little slip of paper of people who attended Gay Alliances of Students meetings. At least half of the names on that list were only first names. So that tells you that while some people were willing to come to the meeting, they weren’t willing to have their full name written down. And, of course, I’m sure there were other people who wouldn’t have dreamed of coming.

I never — actually in my life — have experienced overt homophobia. But that’s probably because I’ve always been a tall, big guy. I wasn’t gay growing up in grade school or even in high school. But sometime after that, I became in touch with that. But I’ve never had an issue.

So I’m not your typical VCU student in 1974. There certainly wasn’t the acceptance that there is today, but I can’t personally claim any particular attacks or homophobic responses or anything. I know they existed.

One of the things I did was speak to a fair number of classes — maybe half a dozen or a dozen — and I could see reactions from certain people, “Oh god, what is this faggot here for?” and that sort of thing. On the other hand, there were plenty of people who were just interested in learning and asking questions.

So VCU was certainly not a hotbed of activity or gay revolution, but it also wasn’t Jesse Helms territory.

So VCU was certainly not a hotbed of activity or gay revolution, but it also wasn’t Jesse Helms territory.

Sharon Talarico: I grew up in a very white town, with only one black family. I wasn’t really around people from other socioeconomic backgrounds. I had a curiosity and fascination with people who were different. I still do. I was a small-town, white, New England girl who made friends with everybody from athletes to bookworms and Bible-thumpers to Black Panthers. Perhaps this is why I was just open-minded to fairness and justice for all, not stuck in some set of my own cultural upbringing.

So I get to VCU and it’s 1971 and we’ve got Vietnam and kids couldn’t vote but they could go to war, and all that stuff was going on, and I got very involved in things that were considered human rights issues and civil rights issues.

It led me to be one of those folks who say if you aren’t part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. That’s kind of how I am as a person, in all kinds of topics. If I see a thing that I think is unjust, I’m probably going to go and try to do something about it — because I’m probably just not patient enough to wait for somebody else to do it.

I was on a group at VCU called CUSA — Council for University Student Affairs — and I had a unique blend in my undergraduate work, in the fact that when I was an undergrad I lived on the MCV Campus but I attended most of my classes on — this is what we called it back in that day — the Academic Campus.

So even though I was in health sciences, I was in the occupational therapy curriculum, so I took most of my classes on the Academic Campus. And I was a person who kind of became known as a bit of a liaison in a lot of ways, and so I was asked to serve on CUSA.

It was because of CUSA and those kinds of campus activities that someone approached me [and said] that there was going to be an organization on campus that wasn’t going to be allowed to become a legitimate or recognized student group. And it was the Gay Alliance of Students.

They told me that they wanted to send out a petition, and they asked me to go out to other student organizations who did have permission to be an organized group and ask for their support.

There’s groups for everything — there was skiing and music and math clubs. All kinds of clubs. I didn’t belong to any of them. But I said I would go approach different organizations to ask them to support the right of this group to become recognized on campus, just like any other group.

So I have to explain a couple things. I need to back up a bit and explain that today, I’m a raging homosexual. There’s no question that I was probably supposed to be a gay person from my birth. But I didn’t get that. And instead, I dated guys, I had boyfriends and I had the opportunity to get married to a couple of guys, but something just told me that I didn’t want to do that. And so I was not, in my own mind, a gay person. But I was certainly a flexible and open-minded person.

I was 29 years old before I first became involved with a female. But, at that time, when I was 21 and 22, I did not have any recognition of myself being lesbian. So I went around and I was asking these different groups, and I don’t remember any of their responses except for one because it was so unusual.

This is about social justice and the right of people to form and meet and congregate.

The group was … [a] religious organization. And I was meeting with a couple of their leaders and I said, “This is about social justice and the right of people to form and meet and congregate, not to mention the fact that our student fees go out to everyone who wants to form a group, whether you’re a part of that group or not. But it’s a human rights issue.”

I’ll never forget, the person said to me, “Well, we understand what you’re saying, but we can’t possibly support you and your people because it goes against our faith.”

So it was unusual to me because there was that assumption that I was a gay person. Because [they believed] only a gay person would be willing to try to get support for this organization. I told them, “I’m not gay, but I’m open-minded and I care deeply about human rights — and this is a human rights issue and it should have nothing to do with your faith. It’s about what’s fair and right for people who are students here just like you.”

Source: The VCU Gay Alliance of Students Collection, 1974-1976, a collection in Special Collections and Archives, James Branch Cabell Library

And so that was the biggest thing that I remember. That had such an impact on me — that I saw people dig in and refuse to be supportive of something that I thought was a no-brainer. I couldn’t understand.

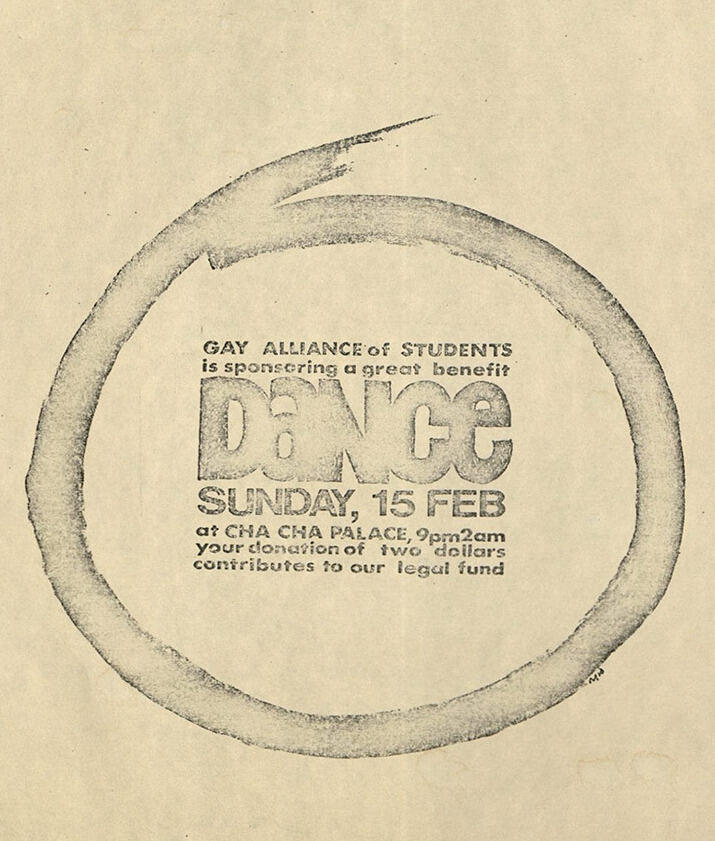

Foery: The biggest fundraiser [the Gay Alliance of Students] did was at a legendary bar called the Cha Cha Palace — and if you haven’t heard about it, you should definitely Google it to see what’s out there about the Cha — it was on West Broad, near VCU. We did a fundraiser there, and I remember thinking that afternoon, “What if nobody comes?” And the place was packed — there were probably 300 people there. And I knew for a fact that they weren’t all gay. So there was certainly support in the community.

On the other hand, I also know that fliers we put up for that event were torn down. I remember going by spots where I knew I had placed fliers and they were gone. Now, maybe somebody took them down to remind themselves to go, or maybe it was “Bubba” didn’t like the idea of [gays and lesbians] on his campus.

So it was mixed. In 1974, there were plenty of people who had never even considered the topic before. People are very less likely today to say “I don’t know any gay people.” Because today, everybody knows at least one person who is gay, whether they realize it or not. But back then, plenty of people would have said they didn’t know any gay people. So it was a whole different time, but there was support and there was negativity.

What happened when the Gay Alliance of Students’ case went to court?

We decided, let’s see if the ACLU would think this is a worthwhile case.

Kriegel: We decided, let’s see if the ACLU would think this is a worthwhile case. And indeed they did. As I recall, the ACLU struggled to find an attorney in Richmond who would take this on. But they eventually [found Richmond attorney] John McCarthy, [who] I think paid a bit of a price among the Greater Richmond community. I don’t think it was overt but my understanding was that he was under some stress or ostracism for even taking the case.

Foery: We filed a lawsuit in federal court, arguing that it was an infringement of constitutional rights to speech and association.

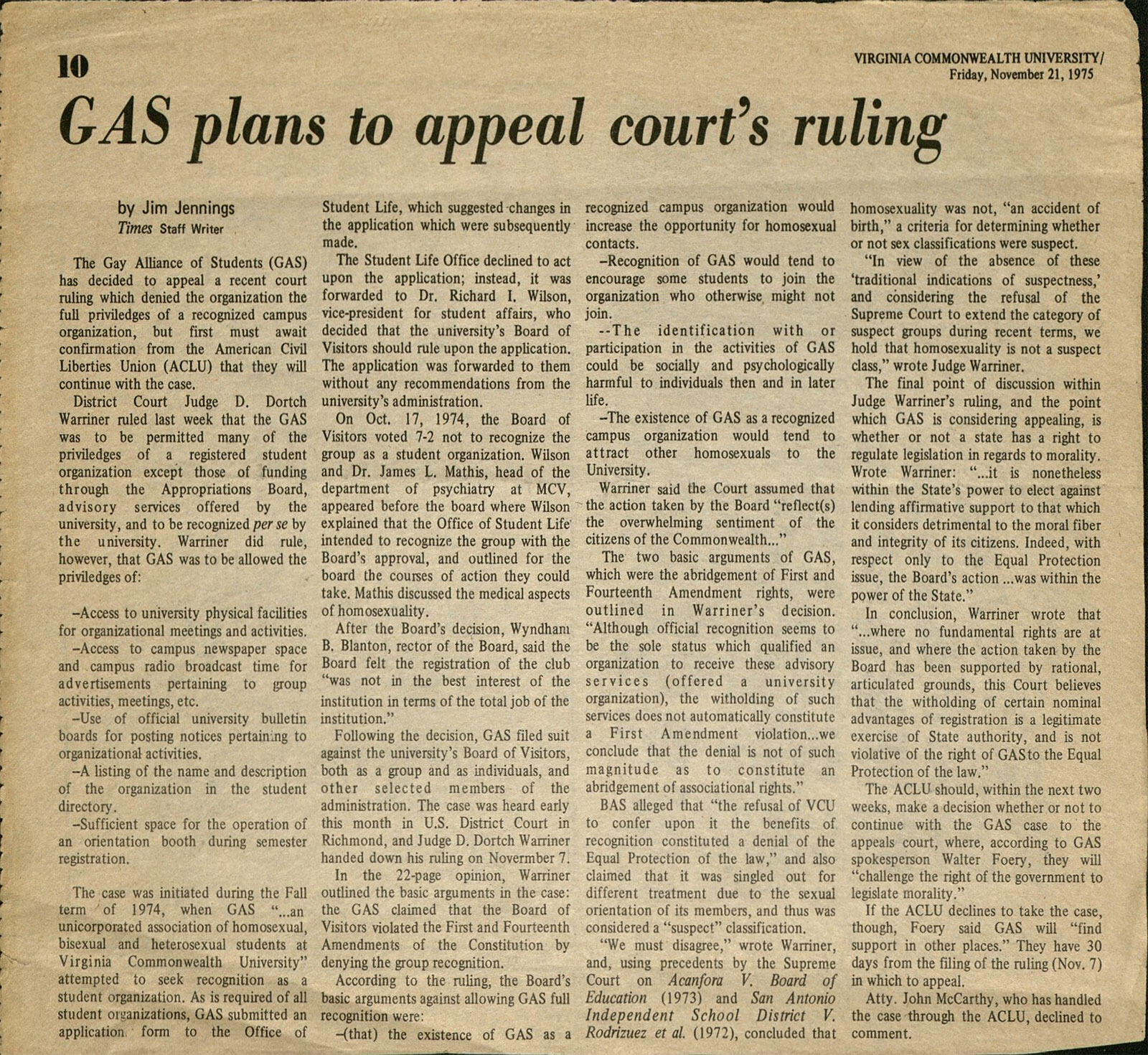

And that was in the district court, and the result of that decision was that the court gave us a few tidbits and gave VCU a few tidbits. The basic question of whether we could be recognized as the Gay Alliance of Students, recognition per se, they denied us. Then for five or six other things that we asked for — the chance to apply for funding, the use of university bulletin boards, use of [student] newspaper and radio for announcements, use of university meeting spaces — and the court kind of split on that. They said, “You can have this, you can’t have that.” But the court said, “No, you cannot have recognition, per se.”

And so we appealed and the university appealed also. They didn’t even want us to be able to use their blackboards.

The Commonwealth Times, Nov. 21, 1975

Kriegel: When we were denied recognition by the university and the court, it was demoralizing to the group. The reason we wanted to meet is because we were demeaned by society. So, it was like being told that we must hide and not be equally recognized, which again was demeaning. It had an impact on group attendance. Speaking for myself, it was pretty clear that people wanted us to keep quiet, and not be seen or heard, which certainly impacted our self-esteem.

After the loss, I think I handed the torch over to Walter Foery, because I was graduating. I finished my undergraduate work in ’74, and I started taking some graduate level courses, but my primary concern was to find full-time work and not to devote a lot of time to different things like this.

Foery: I was the spokesman [for the Gay Alliance of Students]. Whenever news was breaking — when the circuit court decision came out, when the appeal was filed, when the appellate court’s decision was handed down — the Times-Dispatch and [former Richmond newspaper] the News Leader and some of the radio stations would interview me. And my best friend at the time was the news director for the CBS affiliate, and he put me on camera.

It was the impetus for me to come out to my parents. During most of the two-year period, my parents had left Richmond and moved to Florida. But they hated Florida, and they moved back to Richmond just as we were waiting for the decision to come down from the court.

So I realized that if I didn’t have a talk with them, they might sit down to watch the news before dinner and go, “Wait a minute. Isn’t that our son? What’s he saying?” So, realizing that I was a spokesperson and something of a public figure, it meant it was time to talk to mom and dad.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit took up the appeal. What happened next?

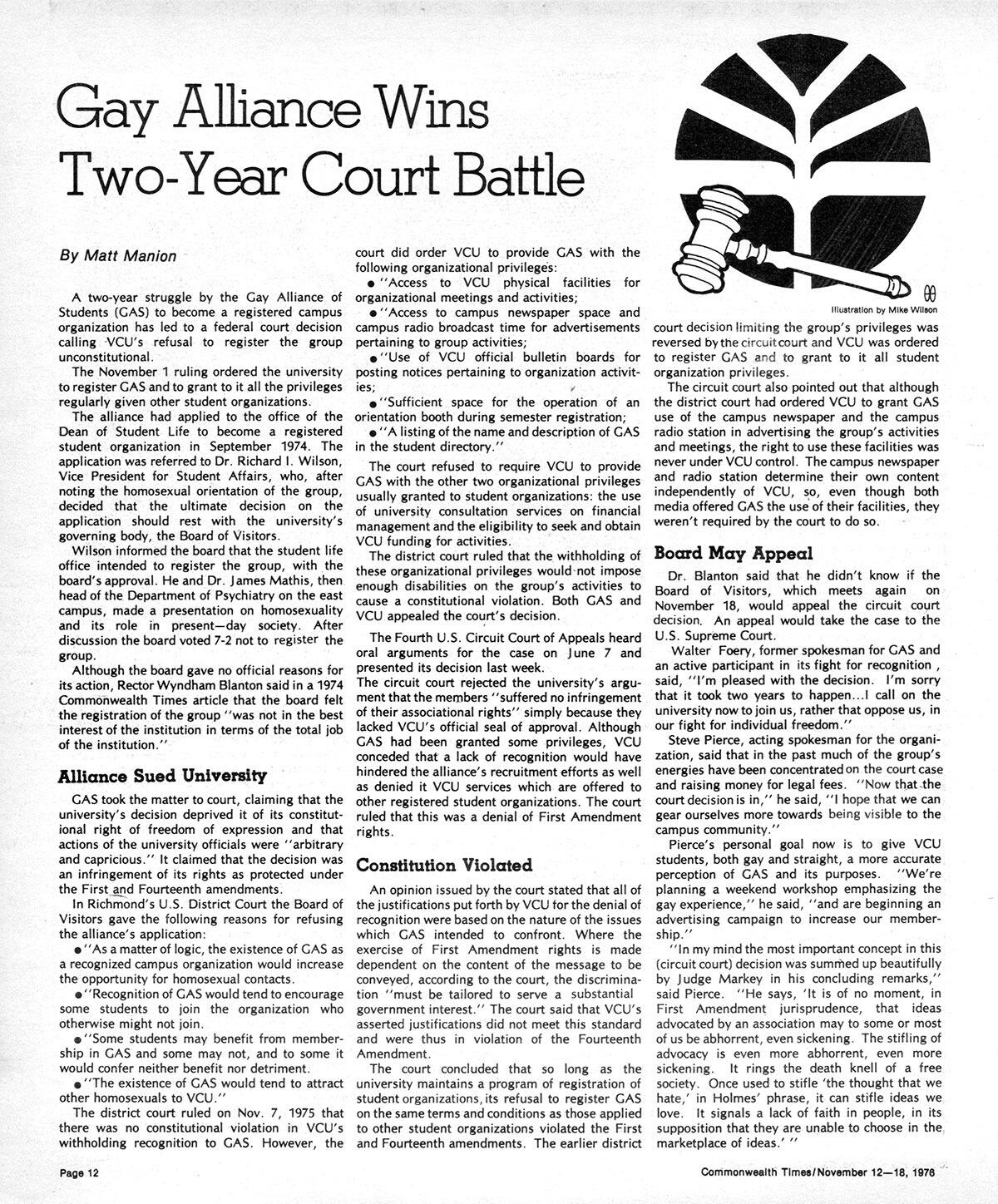

Foery: In the appellate court, we won completely. The university was told, “No, you have to recognize this group and you have to give them the same rights and privileges as any other group.”

That decision didn’t come down until the 28th of October, ’76, so it was a little over two years from the submission of application to final recognition by the circuit court.

We felt thrilled and justified and vindicated.

How did it feel to win?

Foery: My memory is that we were very excited. We felt thrilled and justified and vindicated. But then, we kind of looked at each other and said, “OK … Now what?” And we didn’t have an answer to that question. Not immediately anyway. We worked for two years to win recognition and then we got it, and it was like, “Now what do we do?”

Another memory I have is that I was exhausted. I wanted my life back.

The Commonwealth Times, Nov. 12-18, 1976

Source: VCU Libraries' Commonwealth Times Digital Collection

My boyfriend and I really worked our butts off. It was exciting and wonderful to be doing that together. But when it was over, it was like, “Oh my god, enough.” So after two years, I was ready to go back to being a private citizen, and that’s pretty much what I did. I stayed in Richmond for another four years, I left in ’79. And I remember nothing of meeting with [the Gay Alliance of Students] after we won the court decision. I’m sure I did a few times — at least I hope I did — but I have no memory of that. I was just exhausted.

How do you feel about the lasting and widespread impact of your efforts?

Richmond Times-Dispatch, Nov. 2, 1976

Kriegel: I’d like VCU students today to know that it took courage and some people paid a price. I don’t think I paid a price. I was a student. There were no reprisals against me. I was fearful that if it got to be too big of a thing, I might have trouble getting a job. But I was in a more liberal field. It is my opinion, [however] that it had a negative impact of Stephen Lenton’s career, which breaks my heart, because he was the most compassionate and supportive person [and] teacher that I have ever met. As a dean of student life and a veteran of the Peace Corps, he was all about promoting fairness, justice and human rights.

Foery: It set a precedent in [several] Southern states, the whole circuit. Ours wasn’t the only case at the time — there was another one at the University of Maine, for example. But for the region, it was pretty important at the time. I learned that much later, though. At the time, I just did it because it was the right thing to do.

- Dottie Cirelli is retired from the National Institutes of Health, where she worked for 28 years. She graduated from VCU in 1976 with an M.S. in psychology.

- Brenda Kriegel is a licensed clinical social worker and therapist in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, and is retired from Arlington County Mental Health, where she was a labor organizer who started the Arlington County General Employees Association. She graduated from VCU in 1975 with a B.S. in psychology and earned an M.SW. from VCU in 1979.

- Walter Foery lives in the New York City area and is a senior administrative assistant in the Yale College Writing Center. He studied English at VCU on and off between September 1971 and December 1976.

- Sharon Talarico lives in the Richmond area and is a registered representative with Voya Financial Advisors. She earned both a B.S. (1975) and an M.S. (1982) in occupational therapy from VCU.

LGBTQIA orgs on campus today |

|

Forty years after the Gay Alliance of Students won official recognition as a student organization, an array of LGBTQIA organizations now flourish at VCU. One such group is the newly formed Rainbow Rams. This VCU Alumni Affiliation group for LGBTQIA and ally alumni aims to create a safe environment for VCU Alumni members to support one another, have fun and network, while also raising awareness in the VCU community about the history and experiences of LGBTQIA people in our community. In addition, the group raises funds for scholarships. To join, visit vcualumni.org/alumni/join and choose Rainbow Rams as an affiliation. For a list of LGBTQIA student groups, visit omsa.vcu.edu/lgbt/faqs. For information on Equality VCU, an advisory body representing the concerns of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community at VCU, visit wp.vcu.edu/equality. For inquiries about LGBT History Month events or general VCU LGBTQIA-related inquiries, contact Paris Prince, senior LGBTQ equity officer, at pprince2@vcu.edu or (804) 828-3957. |

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.