May 26, 2016

Measuring flux: New meteorological tower at the Rice Rivers Center gives researchers the big picture on environment and climate change

Share this story

Standing at the edge of the wetlands at the VCU Rice Rivers Center, a 20-foot aluminum tower stands juxtaposed among the wild plants and grasses. There is no detectable movement from its perch on a wooden platform, but it is furiously recording data all day, every day — perhaps the hardest-working researcher in the field.

Gas and wind sensors mounted to the flux tower — aka Rice Rivers Atmosphere Biosphere Interaction Tower, aka Marsh RRABIT — are set to 20 hertz. That means the measurements fly in at frequencies up to 20 times per second. On the whole, the tower instruments collect about 1.7 million records per day on wind speed and direction, carbon dioxide and methane concentrations, precipitation, air temperature, soil temperature and moisture, light, the works.

In any environment, it can be challenging to get an accurate picture of what the atmosphere and terrain are doing. Normally, scientists manually take measurements and samples from smaller locations daily, weekly, monthly.

“You could walk out here and measure over the course of a season how much plant material is produced and you can look at how much carbon gets stored in the soil,” said Scott Neubauer, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Biology in the College of Humanities and Sciences who is jointly leading the project with Chris Gough, Ph.D., assistant research professor in the Department of Biology. “These snapshots-in-time provide a batch of observable data, but it’s limited.”

The 12 instruments mounted to and around Marsh RRABIT are inherently more efficient and faster, providing a constant stream of micrometeorological information. It is a bit of a game changer, though it does not mean scientists can now kick back behind a desk, never to hoof it out to the field in waders again.

The flux tower data will tell researchers how much carbon and methane is going in and out of the footprint it measures (roughly 25 acres from its position to the edge of the forest), and then it is the researchers’ job to get on the ground and figure out where the carbon ends up — in the soil, plants and trees.

“If you can approach it from two different ways, on the ground and an independent approach with a tower, then you can converge on an estimate for greenhouse gas fluxes,” Gough said. “It increases our confidence in the estimates we’re making.”

Discovering the wetland

VCU Life Sciences purchased the tower through funding allocated from the Higher Education Equipment Trust Fund, which provides resources to upgrade equipment needed for instruction and research. It is the first tower to be put in a restored freshwater tidal wetland, an ecological system scientists do not know a ton about, particularly in regards to methane and carbon dioxide coming in and out of the atmosphere. In 2011, the wetlands were restored under a project with the Nature Conservancy.

Understanding the functioning of this type of wetland is at the heart of the project, as is being able to track how a restored wetland functions.

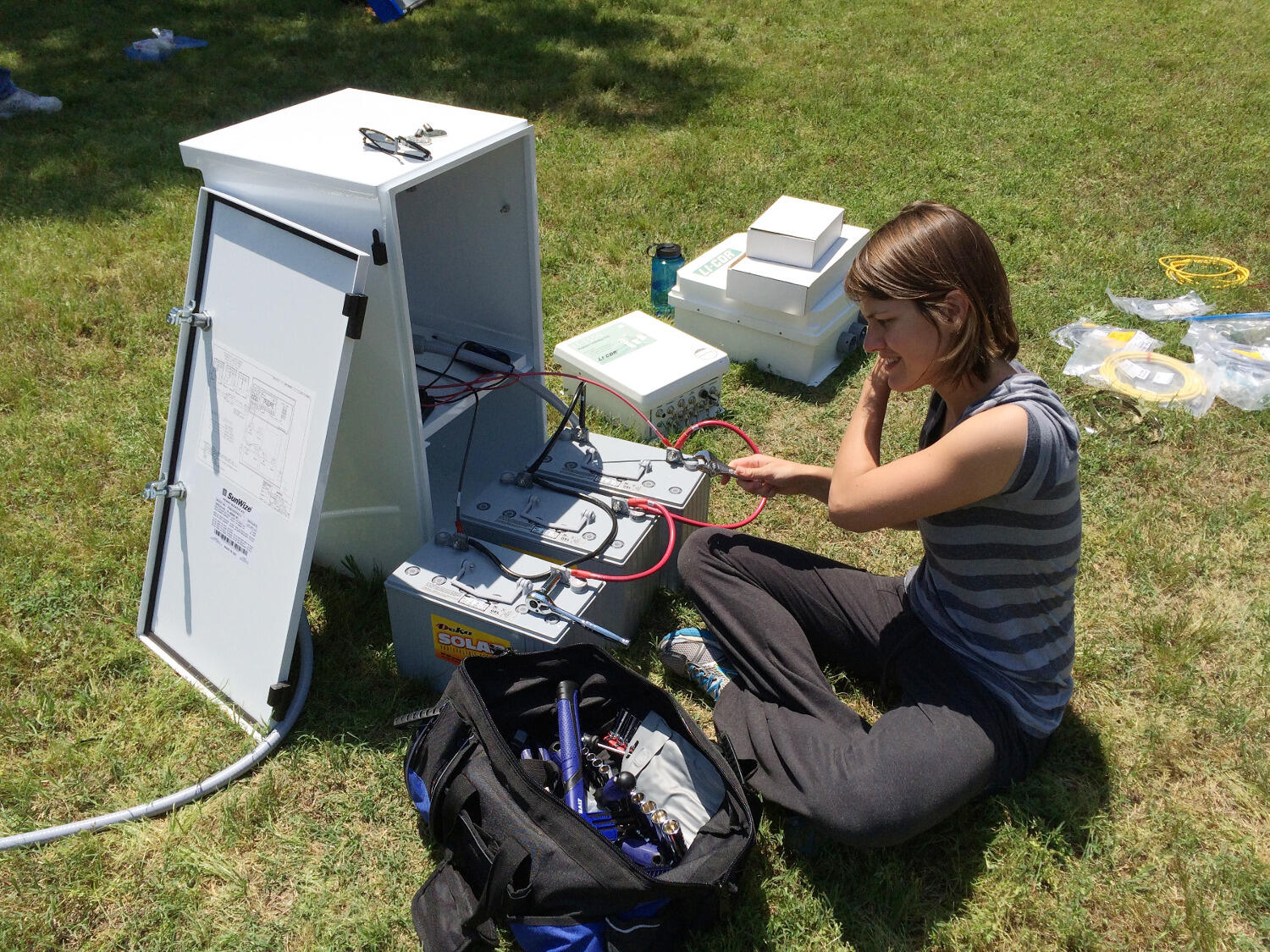

“There are tons of wetlands that have been destroyed all over the U.S. historically, and now, especially after Hurricane Katrina got a lot of attention, people are trying to restore them,” said Ellen Stuart-Haentjens, a Ph.D. student in the VCU Integrative Life Sciences Program. The flux tower project is central to her doctoral research, and she helped assemble and configure the tower.

Wetlands act as sinks for greenhouse gases and are also substantial sources of methane. They help with flood control, protect soil from erosion, and filter water to keep out pollution and toxins. When wetlands are not fully functioning, they simply do not do their job as well.

It is unknown if restored wetlands like the one at the VCU Rice Rivers Center are actually sequestering the same amounts of carbon or emitting similar amounts of methane as an established wetland, and they present a number of scientific question marks for researchers.

“There are very few restored wetlands that people have taken at least carbon measurements out of, so this is going to be one of the first studies looking at that,” Stuart-Haentjens said. “If restored wetlands are not functioning up to what they should be, should we have more regulations on what we do with our wetlands? Or should we change the way we are restoring our wetlands?”

With the new data set, researchers can get answers to these questions and, by being able to precisely quantify the greenhouse gas fluxes between the wetland and atmosphere, produce better predictive models of the carbon cycle.

Data in real time

William Shuart, director of information technology at the VCU Rice Rivers Center, is working on getting the tower hooked up to Wi-Fi so data can be transmitted to a server at the Trani Life Sciences Building on campus. Shuart and Jennifer Ciminelli, data manager and research coordinator, are the keepers of the data. Once the Wi-Fi connection is established, Stuart-Haentjens can begin monitoring the tower remotely from her laptop or even through an app on her cell phone, making sure the instruments are working and that there are no glitches.

Remote access is something that has only just become accessible in the past 10 years, and the technology has revolutionized researchers’ ability to capture high-frequency ecological data from ecosystems, according to Gough.

“What happens is, every 15 minutes or so, the system will transmit data back to one of our servers here on campus and it’s stored in a database,” Shuart said. “We’ll have a website where people can go and look at the current atmospheric conditions at the VCU Rice Rivers Center, what the tide is doing, how much dissolved oxygen is available, etc. Now we have more detailed microclimatology data available.” (Think of the data and graphs on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s website, but on a hyperlocal scale.)

Tons of courses could benefit from a real-time data stream because you can see what the wetland is doing on any given day.

It also allows researchers to share data online in real time, creating a potent teaching and learning platform for VCU professors and students and even those outside of the university interested in the data.

“Tons of courses could benefit from a real-time data stream because you can see what the wetland is doing on any given day,” Gough said. “It makes it more accessible to students because you can say, ‘Hey, it’s sunny and spring. What do you think is going on today based on the theoretical stuff we’ve talked about?’ Then the student can actually see what’s happening in real time and test their hypothesis.”

The hope is that the data will also inform other research, transcending the original questions being asked regarding greenhouse gases.

“So somebody could be interested in what’s happening in Kimages Creek, and they could look at our flux tower data to figure out what’s happening when the tide is up and the whole marsh is creek, and get estimates of what flux is coming from the water,” Neubauer said. “We can see it informing lots of individual scientific questions and allowing others to build off the data.”

Power in numbers

When it comes to flux towers and the micrometeorological data they track, there is power in the aggregate — to take slices of regional and national data in order to understand on a global scale how ecosystems affect climate, and also the other way around. Ultimately, the goal is to generate usable science that could influence policymakers to create regulations around protecting the environment.

The first tower went up in 1990 at Harvard Forest, and there are now about 700 flux towers around the world, many connected to FLUXNET, a global aggregate of tower networks. There also is AmeriFlux, a U.S. and South American network that Marsh RRABIT will join in December as soon as they meet the criteria of having a year’s worth of data.

“This is for people to do large-scale syntheses and models,” Stuart-Haentjens said. “If you have all the information from several ecosystems in the whole U.S., then you can do a lot more.”

For now, the VCU team is part of a group of Virginia-based flux tower scientists called VAFlux. They are working together to determine how they can use combined tower data to develop a carbon footprint for Virginia.

“We have so many ecosystems represented and if you know the kinds of carbon coming in and out of each other’s ecosystems, you can make a model for the whole state,” Stuart-Haentjens said.

VAFlux is also considering how to use the towers as a tool to teach middle and high school students about ecosystem fluxes, and potentially developing a travel course for international students and researchers who are trying to set up and interpret data from their own tower.

The flux tower technology is part of an ongoing effort within VCU Life Sciences to build an infrastructure at the VCU Rice Rivers Center with a broad range of applications that can facilitate a multitude of long-term research projects. It joins a suite of technology and tools, including tidal gages to measure water level and quality and three unmanned aerial vehicles, that give researchers the big picture of what the environment is doing over time. It represents a significant investment in VCU’s research mission.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.