March 23, 2016

Oral history project tells story of African-American schools in Goochland County

Share this story

A new oral history project led by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and John Tyler Community College explores the experiences of former students of Goochland County’s Rosenwald Schools, which were among the nearly 5,000 built throughout the South in the early 20th century to educate African-American children.

The Goochland County Rosenwald Schools Oral History Project features 19 video interviews with 18 participants, fully searchable transcripts and tape logs, photographs of the schools and various related documents.

They were a catalyst, along with local activism and pressure, for improving educational opportunities available for African-Americans in the South in the early 20th century.

The project is a joint venture by Brian Daugherity, Ph.D., assistant professor in VCU’s Department of History in the College of Humanities and Sciences, and Alyce Miller, Ph.D., associate professor of history and chair of Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at JTCC, in partnership with VCU Libraries, which is hosting the digital collection.

“It's important to understand the Rosenwald Schools because they were a catalyst, along with local activism and pressure, for improving educational opportunities available for African-Americans in the South in the early 20th century,” Daugherity said. “Southern school funding disproportionately benefited the education of white schoolchildren, so black activism and support for Rosenwald Schools was an important corrective to the injustices and inequities of that time.”

Rosenwald Schools were a philanthropic effort funded in part by businessman and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, who was appalled at disparities in educational resources between white and black residents in the South.

In 1912, Booker T. Washington asked Rosenwald to use some of the money he had donated to the Tuskegee Institute to construct several small schools in rural Alabama. After that project proved a success, Rosenwald formed the Rosenwald Fund, which ultimately financed construction of 4,977 schools, primarily for African-Americans, between 1917 and 1932.

In Virginia, 367 Rosenwald Schools were built, including 10 in Goochland County.

The Rosenwald Fund required local communities to contribute public funds from both the white and black communities to show partnership across racial lines. However, the majority of public funds came from the African-American communities, which held fundraisers and contributed wages in support of a better education for African-American children.

“One of the reasons that this history is so important is that it highlights the importance and strength of local activism in rural African-American communities in the South in securing educational opportunities,” Miller said. “Stories like the ones in this collection help to highlight the power and agency of rural African-American communities in the South throughout the Jim Crow era.”

The project originated when Daugherity and Miller met a group of Goochland County residents who are converting one of the county’s remaining Rosenwald Schools into a museum. The group asked them to help uncover stories related to African-American education in the county in the early 20th century and to collect video footage that could be used in the museum.

The researchers received grant funding to conduct the oral history interviews and related research from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, the Virginia Community College System and the John Tyler Community College Foundation.

They worked with Cris Silvent, associate professor in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at John Tyler Community College, who videotaped the interviews with the former Rosenwald School students.

As part of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities grant, the researchers partnered with VCU Libraries to preserve and organize the materials to build a digital, online collection of the materials.

“When Brian Daugherity came to me early on to talk about this project, I recognized the historic value of the untold stories he was documenting and the ways they could strengthen our research holdings on the evolving landscape of education for African-Americans in Virginia and across the South,” said Wesley J. Chenault, Ph.D., head of Special Collections and Archives at James Branch Cabell Library.

VCU Libraries actively acquires and preserves research collections of enduring value. “We encourage faculty and researchers to contact us for personalized guidance on projects,” Chenault said. “Archivists are experts in identifying materials of historical significance, regardless of format. Our team regularly meets with faculty and community members to talk about the selection, the accessibility and the preservation of these unique materials.”

Sam Byrd, digital collections systems librarian with VCU Libraries, adds that the digital collection will ensure that a wide audience has the opportunity to learn more about Rosenwald Schools and African-American education in the early 20th century.

“It’s part of our community engagement mission to work with professors and others in the community to make this material available on a wider basis,” Byrd said. “We have a responsibility to make this material available and to continue to make it available long into the future. We have a commitment to preserving, storing and managing materials that are part of our permanent collection.”

From the oral history: Memories of Rosenwald School students

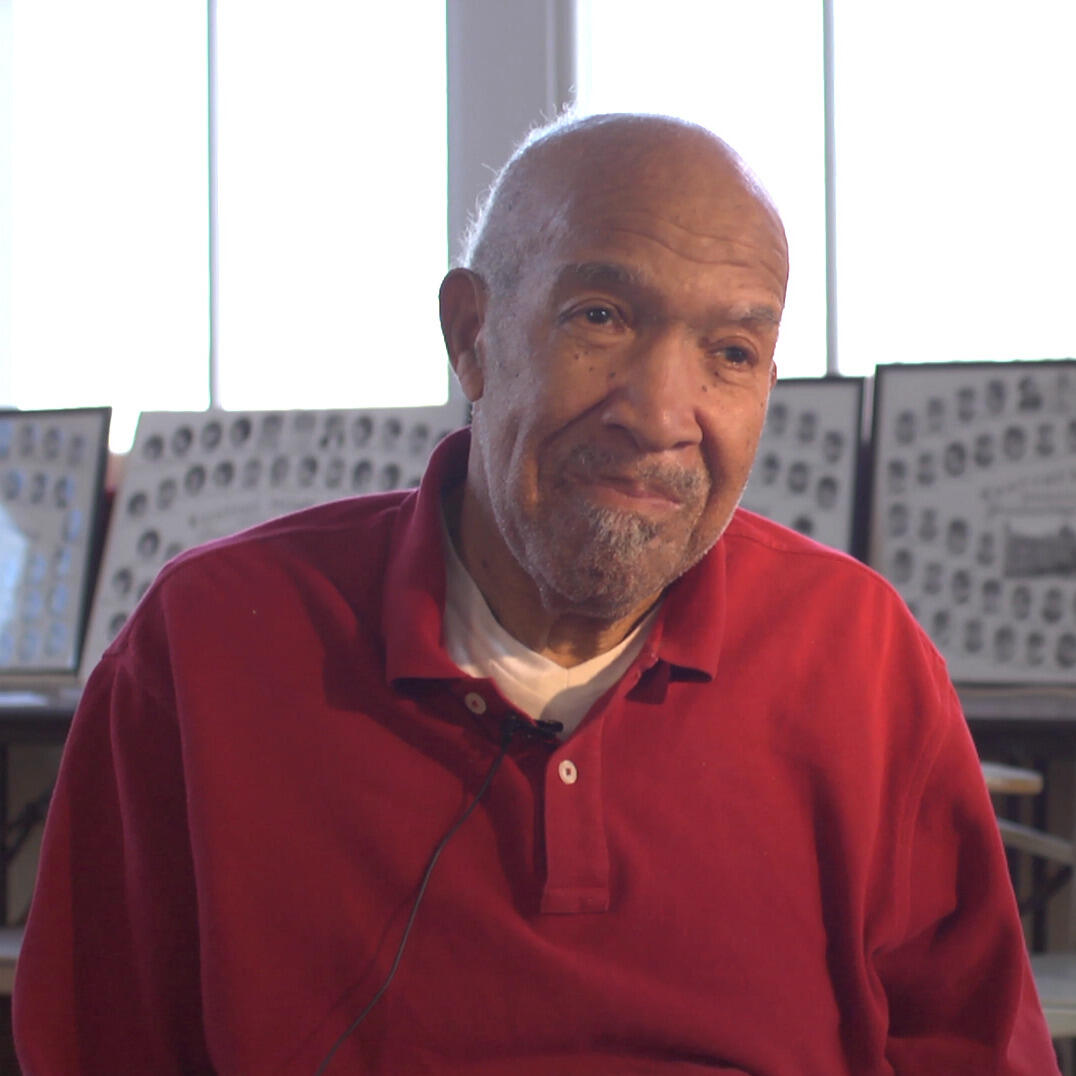

Calvin Hopkins, who attended Second Union School, a Rosenwald School in Goochland County, was among the Goochland County Rosenwald Schools Oral History Project’s participants.

In Hopkins’ interview, he recalls growing up, his experience at Second Union School as both a student and substitute bus driver, his time serving in the Air Force, and more, including how his parents encouraged him to study hard.

“[T]hey would say, ‘Well, you know, we didn’t get the opportunity to go to school,’” he recalled. “‘We’re going to give you every opportunity to go to school and you can make something out of yourself, you know, we are proud of you but you can even make us more proud about attending school and graduating.’”

Another participant, Earline Pace, spoke with the researchers about her family background and childhood in Goochland County, as well as her memories of attending Chapel Hill School and Central High School.

“When you walked in through that door it was [a] two-room school, it was grades one through four, OK, one teacher, and as many students as you could line up chairs to sit in,” she said, speaking of Chapel Hill School. “And when you made it through the fourth grade you go over to what we call the ‘high room,’ those were grades four through seven. One teacher over there, one teacher over here.”

“I was always eager to learn and in an environment such as it was — when the teacher, my first teacher was named Ms. Boston, when she was teaching on grade, all you needed to do was just sit there and listen you going to learn something from the upperclassmen,” she continued. “And I was to the point, I was always very smart, so when a student over in the high room didn’t know the answer to a question, Ms. Cox, who was the teacher in the other room, she would knock on the door and say ‘Could I borrow Earline for a minute?’ And she would ask me the same question and I would answer it by so doing embarrassed the student in the high room for not knowing what was done. So, as I said I was eager to learn and I was very smart if I must say it myself.”

Yet another participant, Curtis Parrish, spoke with the researchers about his family background and childhood on a farm in Goochland County, his memories of Chapel Hill School and Central High School, and his careers in the military, the printing business and the funerary business.

He recalled how the white children initially took a bus to school, but African-American children had to walk — two miles each way, in his case. He also spoke about how his father strongly advocated that the county provide support and supplies to the school.

“Well, see they would bring the textbooks from the white school to the black school,” he said. “But they would take their time getting them there, so that’s the first thing he would get on them about ... And they needed different things, like when you asked me about the repair, who did the repair, like something was supposed to be done before September, you know, he had the whole summer to do it, but it didn’t get done till they got put pressure on them, you know?”

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.