Sept. 4, 2014

Professor's new book explores rise of post-WWI black political movement

Share this story

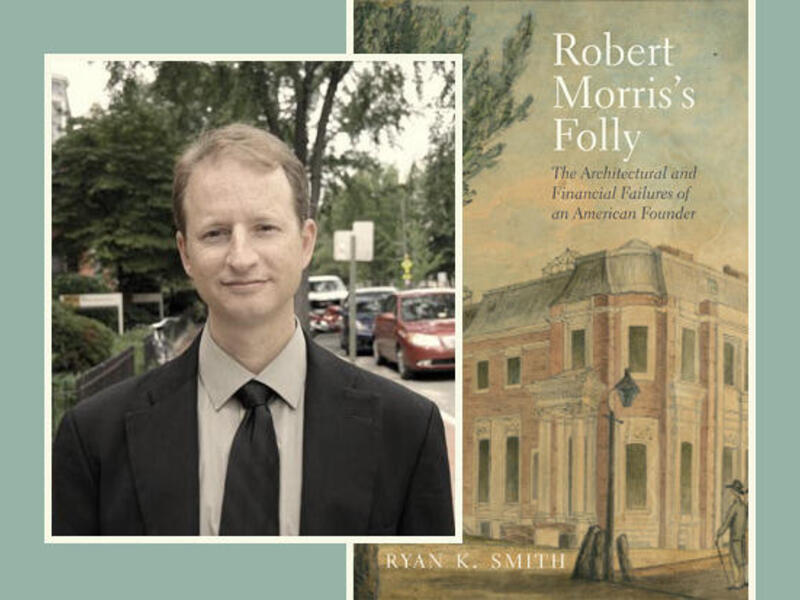

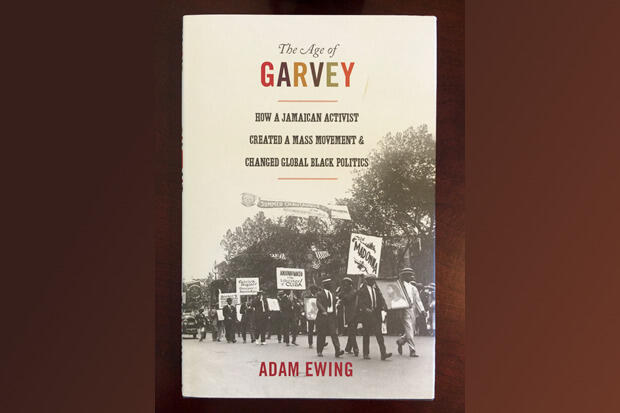

In a new book, Adam Ewing, Ph.D., examines the rise and spread of Garveyism — a race-first political movement led by Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey — across the United States, the Caribbean and Africa following World War I.

Ewing, an assistant professor in the Department of African American Studies in Virginia Commonwealth University's College of Humanities and Sciences, recently discussed the book, “The Age of Garvey: How a Jamaican Activist Created a Mass Movement and Changed Global Black Politics,” and explained how Garvey's story can deepen our understanding of the intersection of racial identity, power and political mobilization.

Tell me a little about Marcus Garvey. Who was he, and why is it important to understand his story?

Marcus Garvey was a Jamaican-born printer, entrepreneur and activist. He came of age around the turn of the century, during an era in race relations that is known as “The Nadir,” a period characterized by the implementation of Jim Crow segregation in the United States and the expansion of colonial rule across most of Africa. In 1916, Garvey set sail for the United States and quickly established himself as the leading figure of the World War I-era “New Negro” movement. His organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, demanded that Africa be returned to the Africans, and sought to mobilize people of African descent from all over the world to bring this about. This organizing was remarkably successful: At its height, the UNIA claimed millions of followers in the United States, Canada, the Caribbean, South America, Europe and Africa. The influence of Garveyism’s spread was profound. The period following World War I was, as my book’s title suggests, an age of Garvey.

What exactly was the Garveyism movement? What were its goals? And what did it achieve?

Garveyites endeavored to unite peoples of African descent who had been scattered across the world by the global slave trade. They argued that this would hasten the liberation of Africa, which they viewed as a precondition to the liberation of black people everywhere. The flashiest manifestation of this project was the Black Star Line, a joint-stock transoceanic shipping line intended to marshal the combined economic resources of the race and to demonstrate its nascent industrial might. Yet it was the more understated elements of the Garveyite program that gave it its enduring importance: organization-construction, institution-building and consciousness-raising.

Does Garvey's legacy continue to resonate today? In what ways?

Following the decline of organizational Garveyism, the movement continued to resonate across the United States, Africa and the Caribbean. Men and women who had grown up in the Garvey movement assumed leading roles in black nationalist, civil rights, trade union, pan-African and African-nationalist organizations. When he was a boy in Lansing, Michigan, Malcolm X was brought to local UNIA meetings by his father. Several African heads of state paid tribute to Garvey by noting his influence of their political development. Garveyism had a formative influence on the early years of South Africa’s African National Congress. In the Caribbean, beyond its resonance in anti-colonial and labor struggles, Garveyism helped give birth to Rastafarianism and is often referenced in reggae music.

What led you to become interested in this topic?

I was drawn to Garvey because I was interested in the mechanics of mass mobilization. I was also interested in the movement’s global reach, and what this meant for black communities confronting seemingly intractable situations in communities spread across continents.

How would you describe this book's central argument?

Garveyism is best remembered as a flamboyant “Back-to-Africa” movement that exploded onto the scene in post-World War I Harlem, galvanized people with flashy parades, costumes and ostentatious business schemes, and then collapsed under its own pretensions quickly thereafter. I argue that, far from a flash-in-the-pan, Garveyism was deeply rooted in black intellectual, social and cultural traditions; enjoyed a sustained and dynamic life as a political practice; and had a resonance in projects as diverse as rural organizing in the Jim Crow South, Caribbean labor politics, southern African millennial religious revivalism and Kikuyu ethnic nationalism in Kenya. Garveyism was the dominant form of black political expression between the world wars.

How does this project fit into your larger body of scholarship?

My work broadly focuses on the intersection of racial identity, power and political mobilization. Studying Garveyism taught me a lot about all three, and I hope it will prove instructive to others as well.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.