Oct. 26, 2017

In new book, VCU alumnus reveals 190-year history of Richmond’s notorious, iconic Virginia State Penitentiary

Share this story

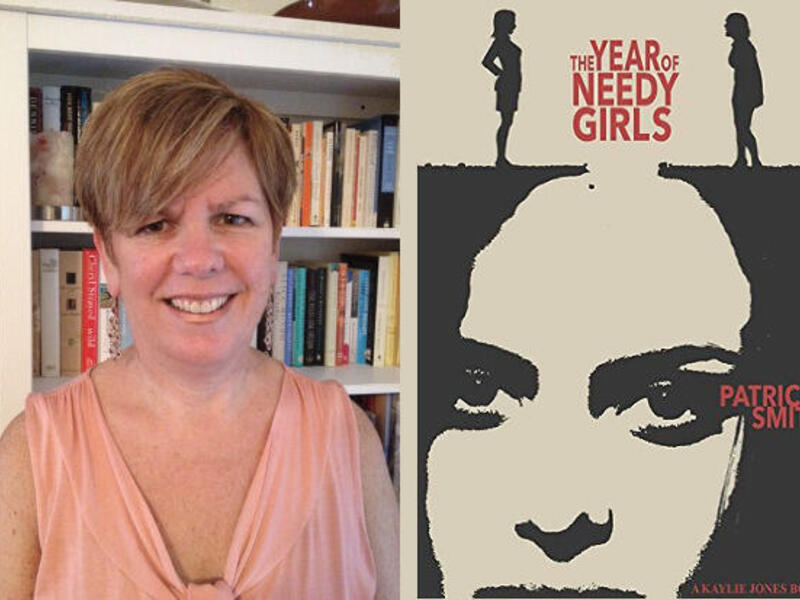

A new book by Virginia Commonwealth University alumnus Dale Brumfield reveals the history of the Virginia State Penitentiary, the Richmond prison that was built in 1800 and that the ACLU at one time called the “most shameful prison in America.”

“Virginia State Penitentiary: A Notorious History” is the latest book by Brumfield, who earned a B.F.A. in painting from VCU’s School of the Arts in 1981 and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from VCU’s Department of English in the College of Humanities and Sciences in 2015.

Brumfield is the field director for Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, as well as a digital archaeologist and the author of eight books, including two histories of the underground press — “Richmond Independent Press” and “Independent Press in D.C. and Virginia: An Underground History.”

He will give a reading and sign copies of “Virginia State Penitentiary: A Notorious History” on Sunday, Oct. 29, from 4–6 p.m. at Babe’s of Carytown’s back room, 3166 W. Cary St. in Richmond.

Brumfield recently discussed his new book, and explained what made the Virginia State Penitentiary so notorious.

The idea to build the Virginia State Penitentiary was originally advocated by Thomas Jefferson. What was Jefferson’s vision for it?

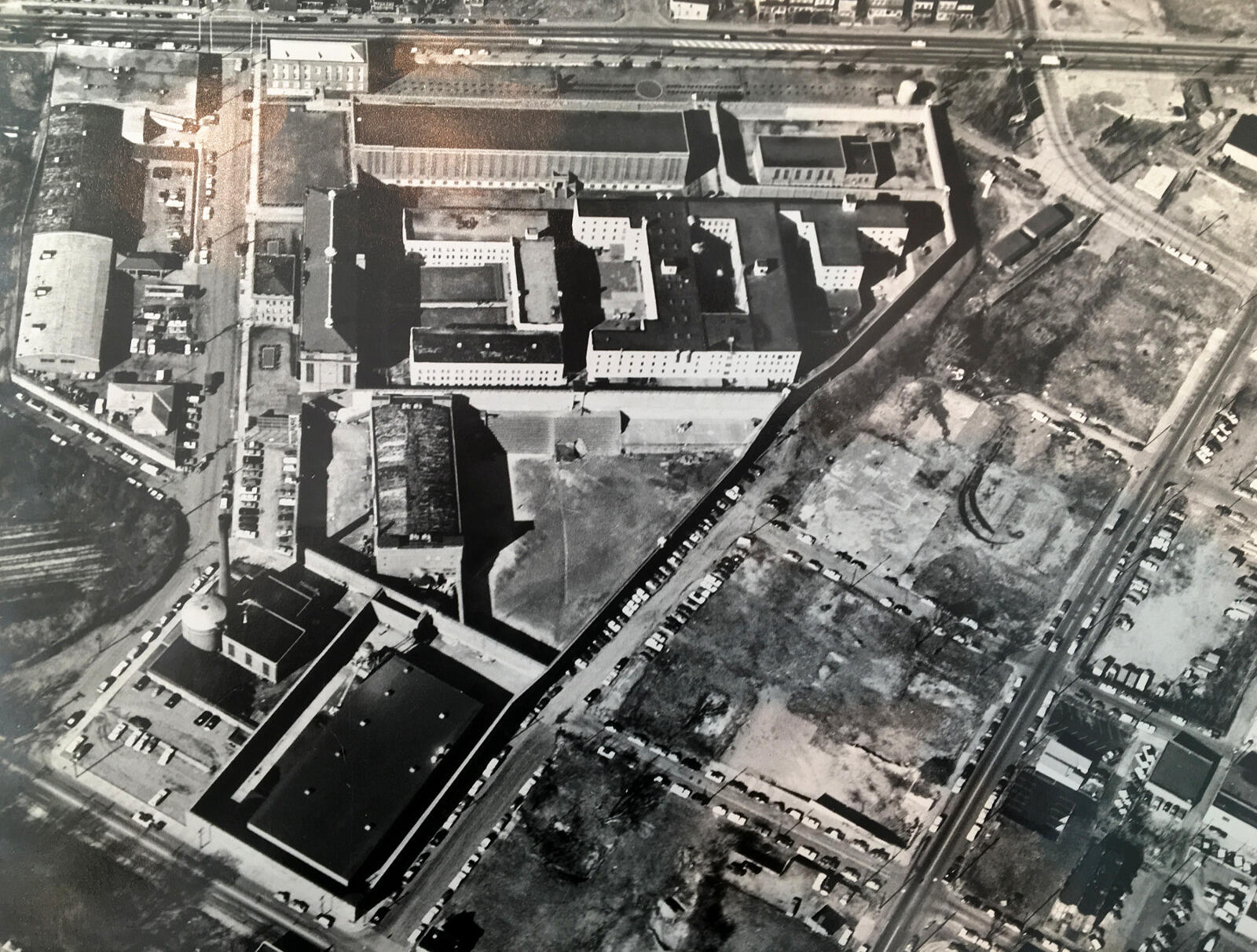

In the fall of 1785, while serving in Paris as ambassador, Thomas Jefferson noticed a method of incarceration in which “an experiment of the effect of labor in solitary confinement” was used. Jefferson agreed with the Pennsylvania Quakers that the legitimate object of all punishment should be discipline, repentance and reform rather than vengeance. Since Virginia’s penal laws had not been reformed in any substantial ways since Jamestown days, Jefferson upon his return advocated his own “labor in confinement” for prisoners, in which they work on public works projects during the day then spend solitary confinement in cells on nights and weekends where they could meditate on their crimes. It took the General Assembly 10 years to embrace Jefferson’s suggestions, but in 1795 they passed major penal reform laws, and then initiated the construction of the Virginia State Penitentiary on the far outskirts of Richmond, in what became the intersection of South Belvidere and Spring streets. The Virginia Penitentiary can thus be considered the first modern prison in America. Jefferson himself actually sketched out a design for a prison based on the French Panopticon, but his designs were not used.

The prison was designed by Benjamin Latrobe, who went on to serve as the architect for the U.S. Capitol. What was the building itself like? What do you think it would have been like to be incarcerated there?

This penitentiary had many problems, and inmates suffered terribly as a result.

Latrobe’s original building was revolutionary for the time, but definitely “form over function.” The main building was a semicircle, with three stories of cells and workshops facing an interior commons area behind a rectangular section composed of three courtyards, a workroom and the women’s section —features unheard of for a prison. Cells were various sizes, with some accommodating several inmates. Since in those days all inmates were required to spend a portion of their sentences in solitary, many dank, unlit solitary cells were added in the basement.

Latrobe was a genius, but this penitentiary had many problems, and inmates suffered terribly as a result. The cell doors had no windows, so guards had to open them to check on the inmates inside, leaving them vulnerable to ambush. Latrobe underestimated Virginia winters, so the prison was unheated, and inmates shivered under a cheap German-made blanket while wind, rain and snow howled through the barred window. There was originally no exterior wall, so passers-by could pass contraband through outside first-floor cell windows. There was no sewage system, so inmates collected waste in buckets then emptied them down a trough into a nearby holding pond, where in the summer the stench became unbearable. This situation remained unchanged for over 100 years.

Your book largely focuses on the stories and personalities of those who were incarcerated in the Virginia State Penitentiary. Who were some of the notable people incarcerated there?

Probably the most famous inmate was former Vice President Aaron Burr, who was held there in 1807 for about 30 days while awaiting trial for treason. He seemed to accept his confinement, telling his daughter Theodosia that “different servants have arrived with messages, notes and inquiries; bringing oranges, lemons, pineapples, cream butter … and some ordinary articles.”

Over a dozen prisoners of the War of 1812 were held briefly there before an exchange sent them back to their flotilla.

In 1954, Henry Lee Lucas was incarcerated for five years for grand larceny. Upon his release in 1959 he later, with his Florida accomplice Ottis Toole, confessed to over 300 murders committed nationwide, although many believed he was lying about many of them to avoid the electric chair for the murder of Kate Rich of Ringgold, Texas. Lucas’ story became the basis of the 1986 movie “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.” Ottis Toole (who was never incarcerated in the Virginia Penitentiary) was posthumously determined in 2008 to be the killer of 6-year-old Adam Walsh, son of “America’s Most Wanted” host John Walsh, in 1981.

Richmond’s most notorious serial killers, Linwood and James Briley, who engineered the worst death row escape in American history from Mecklenburg Correctional, were both executed in the penitentiary electric chair in 1984 and 1985, respectively.

What led the ACLU to eventually call the Virginia State Penitentiary the “most shameful prison in America?”

This dubious designation followed a long line of dubious designations due to the terrible condition of the infrastructure and the treatment of the inmates. In 1806, after being open for only six years, Superintendent Mims wrote to the governor that, “The situation of this place is truly disagreeable and dangerous.” In 1919, the State Board of Charities and Corrections called it a “torture chamber” and the Prisoner’s Relief Society of Washington, D.C., the same year called it “the most mismanaged prison in America.” In 1968, Frank Adams, executive secretary of the Virginia Council on Human Relations, called the penitentiary “a Dachau on Spring Street.” A July 1990 inspection by the ACLU for the National Prison Project and representatives of the Virginia attorney general’s office revealed the buildings were filthy and roach-infested; the summer heat was unbearable; there was standing water everywhere; and the toilets frequently stopped up. After this tour, the penitentiary became “the most shameful prison in America.”

In addition to being an author, you are the field director for the nonprofit Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. In what ways does your work in opposition to the death penalty inform this new book?

It actually worked the other way around. I had finished the manuscript and turned it in to the publisher before the VADP field director job even came available. While I was anti-death penalty before, it was this research that once and for all convinced me that the inequitable racist and classist applications of the death penalty in Virginia through the years renders it a medieval and barbaric remnant of the 19th century that needs to be abolished. In 2016 the General Assembly and Governor McAuliffe shrouded the execution process in secrecy by shielding the execution procedure, the names of the pharmacy providing the lethal injection drugs and even the drugs themselves. This is a continuation of a legacy of institutional racism, now masked in heavy secrecy. Virginia will never come to terms with this racist past as long as she continues to kill people.

What sort of research did you undertake to tell the 190-year history of this prison?

It was extensive. Luckily, most of the penitentiary archives are located in the Library of Virginia downtown, so I camped there for weeks just requesting and reading files and documents. Many documents are on microfilm, and some are listed in online digital libraries, but it takes a lot of time and work to discover, as many do not show up in Google and are not searchable. I call this process “cultural archaeology” to weed out stories that most researchers give up on.

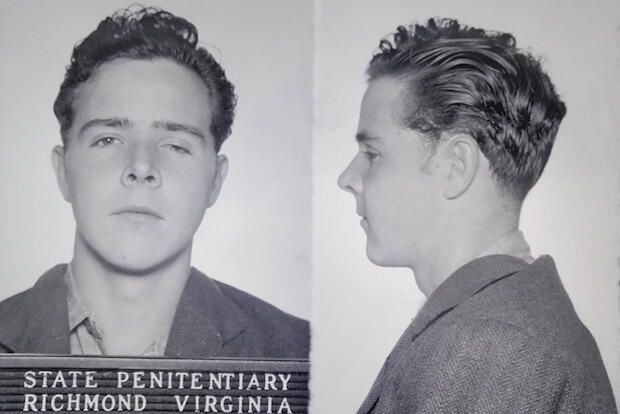

I knew the stories were almost unbelievable in their own rights, so that made the pressure to be as accurate as possible very acute. No embellishment was necessary. For example, I researched the backstories of over 100 Virginia executions, with my goal to present the narratives of the arrest, convictions and executions of those mostly young black men dating back to 1908, to try to ascertain the true or at least most likely stories behind their crime, arrest, conviction and execution. In my research I found massive legal and social discrepancies, including coerced confessions, misidentifications, trials with no legal counsel, police threats of lynching and other inequities. It was a sad and horrifying realization what these men and two women endured in the commonwealth’s sometimes frenzied quest to solve crime.

As you were researching and writing this book, did any story about the Virginia State Penitentiary and its inmates resonate with you the most?

I was affected by the case of Winston Green, the second man executed in Virginia’s brand new electric chair. He was a mentally disabled 17-year-old who, in 1908, reportedly stopped a 12-year-old girl on her surrey and ordered her off. He either grabbed her or just scared her, but he ran away when she screamed. He was pursued and caught by a posse of 25 white men, who beat him and took him to the girl’s house where she supposedly positively identified him. At his trial he had no legal counsel, and he went to the electric chair — all based on that single identification.

I am also haunted by the story of Thomas Nowlin. In 1875 he was serving four years for arson and working as a sweeper in the penitentiary kitchen when he fell in a tub of boiling coffee and was horribly scalded. He died five days later of his burns. He was 10 years old. Virginia had no reformatories at the time, and inmates as young as 9 years old served time packed into cells with adult killers and rapists. I have an entire chapter devoted to this horrible, no-win situation.

Subscribe for free to the VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Monday and Thursday during the academic year.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.