July 24, 2019

How a VCU alumnus helped create Baltimore’s iconic Oriole Park at Camden Yards

Share this story

When David Ashton stepped into Oriole Park at Camden Yards in 1991, the Baltimore baseball stadium was just steel beams and brick. In a controversial move, the city was preparing for the Orioles to leave the aging Memorial Stadium behind and settle into a new home downtown.

Standing with Ashton on the bare-bones construction site was Janet Marie Smith, then vice president of planning and development for the Orioles, who laid out her vision for Camden Yards. She wanted him to design a new park that was special and timeless, that had the flavor of a bygone era — a park that would bring the fans back home.

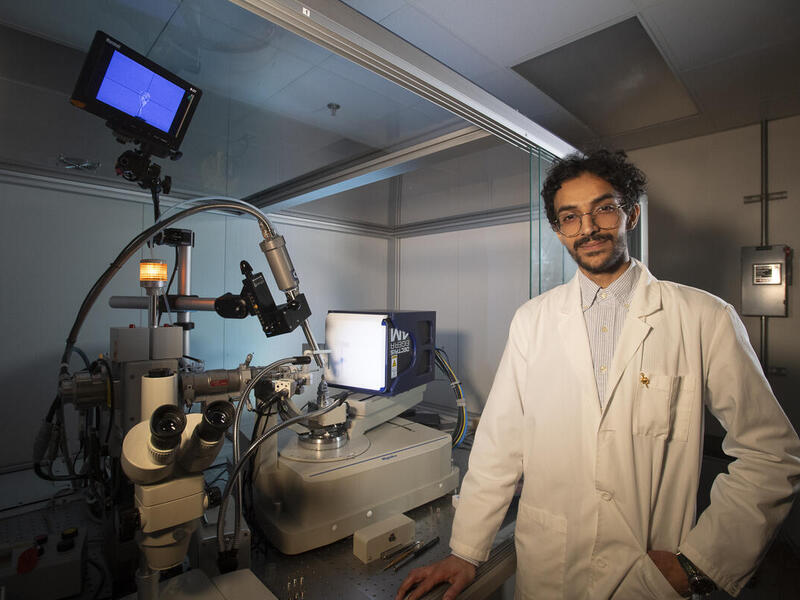

Smith spoke to Ashton like he had done this before. He hadn’t. Though the Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts alumnus was a seasoned designer, he feared that he was in over his head. Ashton Design was just one of many local firms Smith had contacted in her search for someone who could give the skeletal park personality and character. To get the job, Ashton would be competing with companies whose resumes were much longer.

Six months later, Ashton delivered designs for a baseball stadium so unique that franchise owners around the country would soon be clamoring for one just like it. On his first pitch, he had changed the game.

Like the good old days

Ashton never expected Camden Yards to be such an enormous success. After his initial tour with Smith, he returned to his office and the scale of the Orioles project began to dawn on him. As the owner of a small design firm, the bulk of his professional experience was in print. Nothing he had done could compare to designing every single graphic and decoration in a facility meant to seat 48,000 people.

“I realized that the biggest signage project I’d ever done was a 4-by-8 sign for a housing development,” Ashton said. “I had no idea what I was doing; I was just using my instincts to know what was right.”

Like many kids who grew up in the 1950s, Ashton was a baseball fan. Mickey Mantle and Joe DiMaggio were icons for millions like him, and the parks where they played were equally beloved. At that time, baseball was still a neighborhood thing. Ballparks were brick and iron, just like the apartments across the street, and you could watch the game from the rooftops. When Roberto Clemente hit a home run out of Chicago’s Wrigley Field, it landed on the curb.

But in the ’60s and ’70s, as Major League Baseball expanded west, new stadiums were designed to be cheap and multipurpose to accommodate a city’s baseball and football teams. As a result, those parks ended up as symmetrical, utilitarian designs featuring massive concrete façades and artificial grass.

“The ballparks were cookie-cutter things,” Ashton said. “They weren’t all that exciting. And it hurt the game of baseball, because it took the people away from the action.”

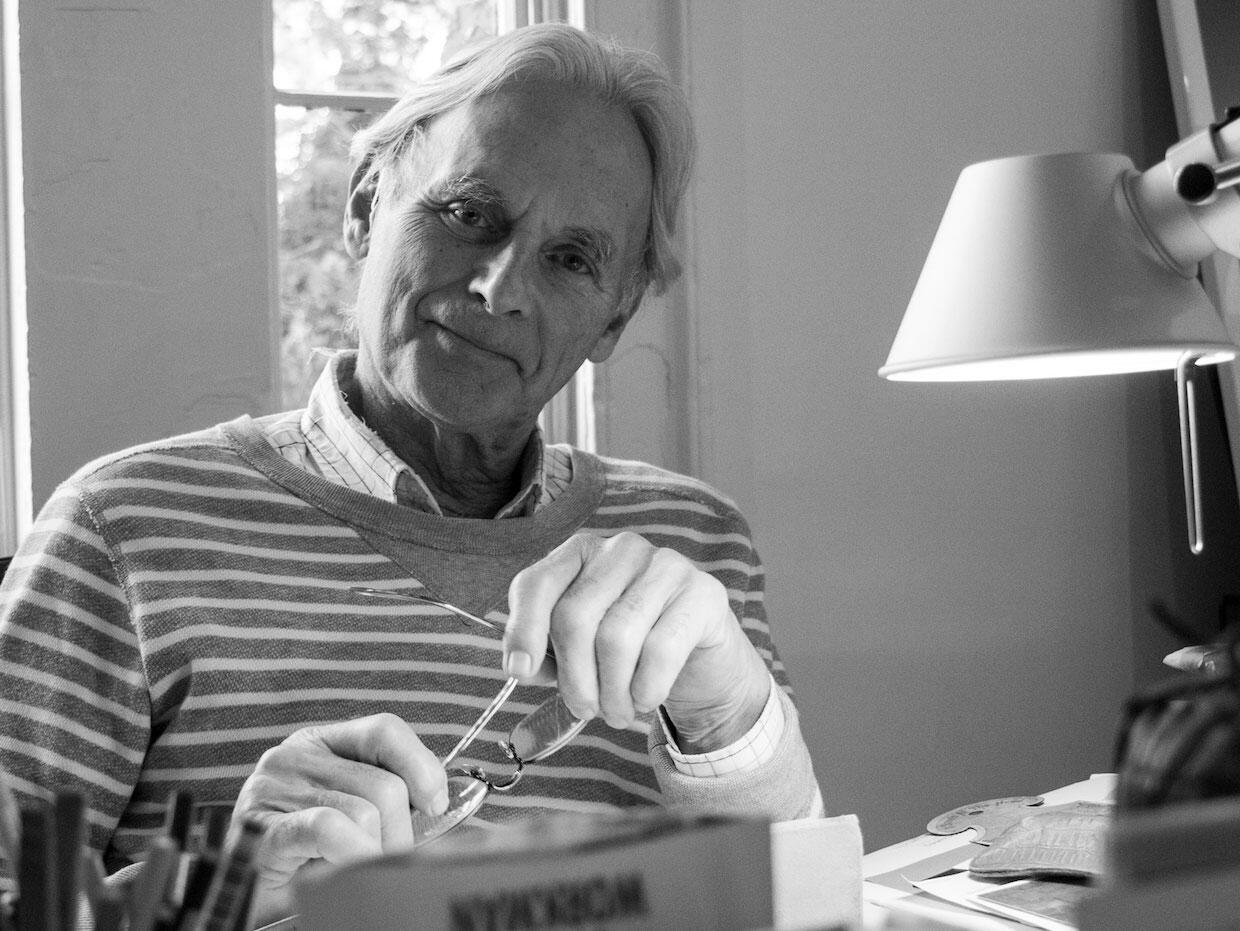

When thinking about how to engage Orioles fans again, Ashton’s instinct was to look to the beloved, folksy ballparks built in the 1910s and ’20s. Incidentally, one of his favorite hobbies was collecting antiques; he had even restored a period farmhouse. With the team’s history stretching back to the 1880s, Ashton thought perhaps his love of Americana could give the new ballpark some retro flair.

‘So close, it’s creepy’

“I just procrastinated and procrastinated,” Ashton said, “because I didn’t really know what to do. Finally, Smith called me up and said, ‘Are you going to send us a proposal or not?’”

He scrambled, copying rough sketches he’d made and bundling them together into a package secured with string. He printed the Orioles logo on the cover and sent it to Smith’s office.

The next morning, he was hired.

He later discovered that his proposal was chosen because it was the only one with the team’s logo on it, instead of the design firm’s.

By the time Camden Yards opened to the public in 1992, the steel beams and brick had been transformed into a resplendent open-air park, nestled into downtown Baltimore just off the Inner Harbor. The stadium’s orange accents and lush green signs and seating transport visitors to the turn of the century, with serif font signage, block lettering, swirling wrought-iron accents and hand-drawn wall illustrations that evoke the earliest days of urban baseball. The neighboring B&O Warehouse, built in 1899, was renovated and converted to office space for the team, providing an authentic counterpart to Ashton’s antique stylings.

If you go to Oriole Park today, more than 25 years after its construction, you can still see many of the signature features Ashton and his firm designed. The distinctive 19th-century clock above the scoreboard, oriole weathervanes and charming concession-stand logos all originated from his sketchbook.

“Most of the stuff that got built at Camden Yards is so close to those sketches, it’s creepy,” Ashton said.

Leaving a national legacy

After opening day in 1992, Ashton became a local celebrity in Baltimore. He gave talks about his design, and the Orioles hosted the 1993 MLB All-Star Game. Soon, the requests for other stadium renovations started coming in from around the country. The Boston Red Sox hired Ashton Design to update historic Fenway Park, and the Los Angeles Dodgers enlisted the firm to lend Dodger Stadium a similar retro-cool aesthetic. Today, the Dodgers own the second most Instagrammed location on the planet.

Still, Camden Yards remains in a league of its own.

“As soon as you walk in, it had that cathedral feeling. You thought immediately, ‘This place will stand the test of time,’” said Buck Showalter, Orioles manager, in an ESPN story. “This was a park that you thought other teams would copy. And that’s exactly what has happened.”

Baseball fans love to argue over which ballparks are better than others, but Camden Yards commands a degree of respect rarely offered to contemporary stadiums. Look in any list of the best ballparks in the country, and Oriole Park is bound to appear near the top — right next to the places that inspired it.

Despite its fame, Ashton said the historic significance of his work still hasn’t hit him.

“I’m still waiting for that,” Ashton said. “I don’t realize it when I’m breaking the mold. I just do what I think is right.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.