Nov. 5, 2014

Forensic science department hosts its third CSI workshop for mystery writers

Students and author Ellen Crosby teach enthusiasts

Share this story

Picture a small cardboard box, thickly striped with gold and black tape. It’s numbered and labeled (“6” and “feel me” respectively). Inside — underneath a black felt top — a pinecone waits to be identified by touch alone. Fourteen similar boxes — encasing cloves to smell or loose change to hear — are nearby.

With this exercise in sensory perception, Michelle Peace, Ph.D., interim chair of the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Forensic Science, part of the College of Humanities and Sciences, began the third edition of the CSI Workshop for Mystery Writers on Oct. 17. The program starts with a crash course in forensic science techniques, such as studying blood spatter and identifying fingerprints, followed by a crime-writing workshop led by mystery writer Ellen Crosby.

Inaugurated in 2012 as a program geared towards 12 to 15 year olds, the CSI Workshop has since evolved into one that is largely for adults — such as Cynthia Gibbs and Rika Dotson.

As founder of Science Pub RVA, a group that connects curious laypeople with local scientists to chat about science, Gibbs is always on the lookout for ways to engage with science for fun. The CSI Workshop fit the bill.

As for Dotson, her husband surprised her with the workshop as a gift. Although she does not work in science, Dotson was thrilled.

“He’s convinced that if the TV is on, it’ll be on a crime show,” Dotson said, noting that she was “coincidentally” wearing a “CSI” shirt when she received the gift.

Kimberly Longbricco shares Dotson’s passion for forensic science. One of three teenagers attending the workshop, Longbricco was motivated by her homeschooling mother, a love of Stephen King and a burgeoning interest in the field.

“I’ve been studying forensics broadly for about a year,” she said, “taking online courses and finding articles.”

To get an understanding of how trustworthy eyewitness testimony can be, Peace divided participants into two groups and instructed each to think about the registration table they had passed on their way in. Members of one group worked together to generate a composite list of observations, while the other group’s members worked separately.

Unsurprisingly to Peace, the latter group’s observations were better.

“Eyewitness testimony is wrong the majority of the time,” Peace explained. “People generally are just not that engaged with their surroundings.” For this reason, “investigators prefer to have a bunch of different little stories instead of one big story,” because a collection of stories offers “more valuable, probative detail.”

After a final preparatory lesson — this one on the distinction between classification (putting items together in a group of similar objects) and identification (individualizing an object to a specific origin) — participants moved to lab work. Crosby, a former journalist, observed the lab stations and strongly urged the participants to take copious notes at each station.

“It’s really important,” she said. “You can never take enough notes. … Write it all down, because the one thing that you’re going to need when you go back to write that story is the thing you forgot to ask.”

Twelve of Peace’s forensic science students manned six stations teaching the rudiments of six sub-disciplines of forensic science:

1) Kelsey Winter and Joe Parian described fingerprint classification patterns (arch, loop and whorl) and identification characteristics (bifurcation, ridge ending and island) before engaging participants in using powders, brushes and tape to lift, classify and identify fingerprints.

2) Tyson Baird and David Millard explained how to determine and analyze the chemical (pH) and physical (particle color, size and texture) differences among soil samples before inviting participants to solve the mystery of an unknown sample.

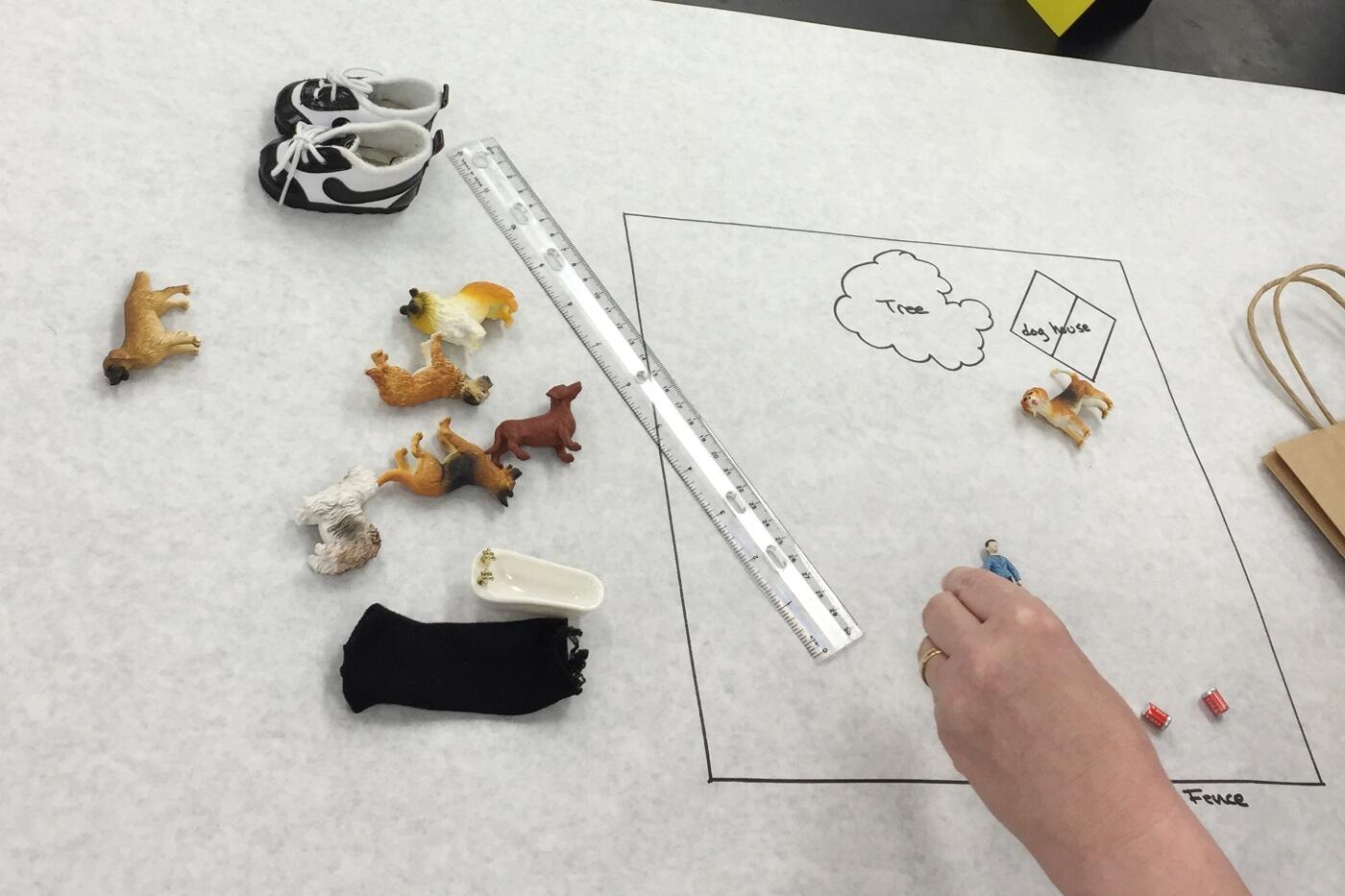

3) Brandon Coffrin and Shane Wolff first asked participants to use various figurines to create crime scenes within spaces outlined and detailed on paper. They then instructed everyone to rotate and sketch someone else’s scene, emphasizing the use of scale, legends and keys to improve legibility. Finally, participants recreated each other’s crime scenes using their sketches.

4) April Solomon and Tiffany Layne guided participants through an experiment with one type of bloodstain pattern analysis: using the diameter of bloodstains to determine the distance fallen. Using “blood”-filled pipettes mounted at various heights, participants created, measured and observed features of their own samples.

5) Amanda Mohs and Sara Dempsey taught participants about the differences between human and other types of animal hair before showing them how to use compound microscopes to compare samples.

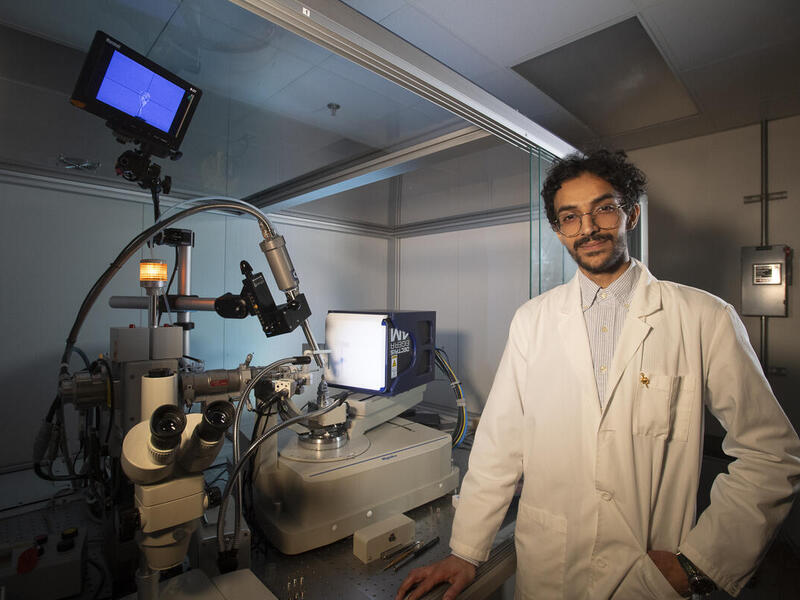

6) Sasha Hayes and Annessa Burnett provided a general orientation to toolmark analysis before facilitating participants’ use of stereo microscopes to observe and classify impressions on pieces of wood and to identify the tool that made them.

Once sufficiently primed in how crime scene investigations work, participants were ready for part two of the seminar — the crime-writing workshop. Crosby treated participants to a brisk, two-hour tour of her life, work and craft.

After discussing the many story types within the mystery genre (e.g., the cozy, the caper, the police procedural), Crosby analyzed the components of a mystery, including crime, suspects, clues, alibis, motives and, of course, the person who investigates these.

If this person is a detective, Cosby explained, she has a professional motivation for her involvement in the case, and writing about her is relatively easy. But things are more difficult with others.

“An amateur sleuth must have a reason for getting involved,” Crosby said. “Otherwise, you know what you’ve got? A nosy person.”

Crosby also introduced the “big three” elements of any story: character (“Everybody in your cast has to have some skin in the game.”); setting (“Don’t make the background secondary to your story.”); and plot (“On every page, someone should want something, even if it’s only a glass of water.”).

Insights gained from Crosby’s four decades writing both as a journalist and as the author of soon-to-be nine mystery novels, could save the novices from committing some embarrassing gaffes. A number of notoriously troublesome areas of knowledge include weapons and guns, cars, geography and history. Crosby herself once had a general who showed up at the Battle of Middleburg — when he was already dead.

“And I heard about it,” she said. “If you do research for your work, get it right. If it’s wrong, you’re going to hear about it.”

Crosby also emphasized the importance of finding one’s own voice, advising writers not to censor themselves in the first go-round.

“Just write; just get it down,” she said. “And then, when you’re done, you can go back and revise.”

To illustrate the way that ideas come from everywhere, Crosby recounted overhearing a young woman in an airport bathroom say about her lost phone, “Well, 99 percent of the time it wouldn’t ever happen again, but what about the other 10 percent?”

“It ended up in my book,” she said.

Looking at the bigger picture, Crosby spoke to the importance of what motivates people to write. “The writers I know who write and are successful can’t not write,” she said. “None of us is doing it for the money; you do it because you just have to do it and you’re passionate about it and you think you have something to say.”

Throughout the workshop, participants mentioned the influence of several mystery writers, including VCU alumnus David Baldacci and Patricia Cornwell; by the end of the evening, Ellen Crosby had become the latest to make her mark on our community.

“I’m really proud of this program,” said Peace, who has been teaching in and developing VCU’s forensic science program since 1999 — serving as the department’s interim chair for the past four years.

Part of the department’s mission is to support the forensic science community through education and research, notably including the Service Learning course that Peace co-teaches with Jo Murphy, communications and program coordinator, whom Peace describes as “the heart of the department.”

According to Peace, VCU has one of the oldest forensic science programs in the country, with about 400 undergrads and about 40 graduate students. And as long as shows such as “CSI” and “NCIS” continue to be the world’s most-watched TV dramas, these numbers are likely to grow.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday. VCU students, faculty and staff automatically receive the newsletter.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.