Feb. 22, 2019

VCU history professor featured in Sammy Davis Jr. documentary airing on PBS

Emilie Raymond, an expert on 20th-century American politics and culture, provides commentary on several moments of Davis’ story.

Share this story

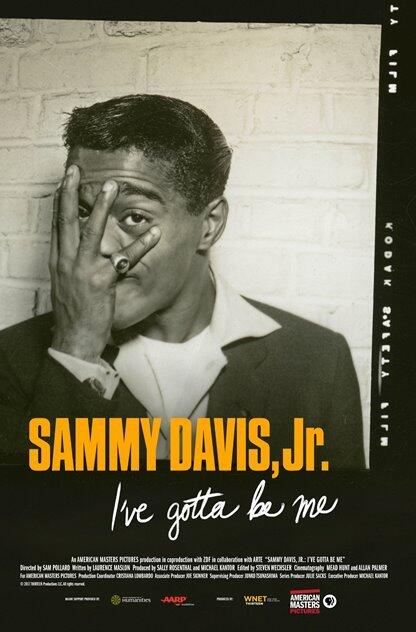

A new feature-length documentary, “Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me,” that debuted this week as part of PBS’ “American Masters” series, features Virginia Commonwealth University history professor Emilie Raymond, Ph.D., an expert on 20th-century American politics and culture and author of “Stars for Freedom: Hollywood, Black Celebrities, and the Civil Rights Movement.”

The documentary — which explores the legendary black, Jewish performer’s six-decade career and journey for identity amid the struggle for civil rights and racial progress — includes commentary by Raymond, alongside interviews with celebrities such as Harry Belafonte, Whoopi Goldberg, Billy Crystal, Norman Lear, Jerry Lewis and Kim Novak.

“I was honored to be included, and to know that my research had contributed to the filmmakers' understanding of Sammy Davis Jr.,” Raymond said. “The producer told me that my book ‘Stars for Freedom,’ which discusses Davis' career in Hollywood and his role in the civil rights movement, had basically been ‘required reading’ for the production staff.”

The documentary took Raymond, a professor in the Department of History in the College of Humanities and Sciences whose research focuses on the intersection between Hollywood and politics, as well as the influence of the civil rights movement, to New York. They filmed the interviews in a Greenwich Village brownstone made to look, Raymond said, “like the luxurious office every professor wishes she had!”

“The director, Sam Pollard, is a renowned filmmaker who has worked on a number of documentaries involving the civil rights movement, including the ‘Eyes on the Prize’ series and ‘4 Little Girls,’ and proved to be incredibly thoughtful and gracious in person. I was grateful to see that Davis' life story was in such good hands.”

In the documentary, Raymond provides commentary on several moments of Davis’ story, including his appearance on NBC’s “The Colgate Comedy Hour” in the 1950s. Raymond describes how host Eddie Cantor came over after Davis’ dance performance, put his arm around him and mopped Davis’ brow. Such an intimate moment between a white man like Cantor and a black man like Davis had rarely been seen on television at the time.

Raymond talks about Davis’ pursuit of the role of Sportin’ Life in the 1959 musical film “Porgy and Bess” that starred Sidney Poitier and Dorothy Dandridge. She also describes how the Rat Pack supported John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign.

“After Kennedy won the election, [Frank] Sinatra put together one of the inaugural parties. And, of course, Davis was going to be invited,” Raymond said.

Then Kennedy disinvited Davis from the inauguration party, canceling his performance out of concern that Davis, who had married white Swedish actress May Britt, would offend white Southern voters. Davis was deeply hurt.

“[JFK] didn’t take Harry Belafonte off the list and Belafonte had a white wife as well,” Raymond said. “But there was something about Davis. I think he was seen just as more of a lightning rod for controversy.”

In the documentary, Raymond also gives context to Davis’ growing involvement in the civil rights movement toward the end of the 1960s.

“One thing celebrities could do was draw attention to the civil rights movement. They had the ear of mainstream publications. They had a lot of fans, both black and white fans, and mainstream fans. And they were able to reach audiences that movement organizations and movement activists couldn’t necessarily do,” Raymond said. “Sammy Davis Jr. did the walk from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. I consider him sort of the benefactor of the movement. He raised about $750,000 for movement organizations, which is about $5.5 million in today’s terms.”

Grappling with Davis’ motivations, insecurities, triumphs, self-destructive tendencies and legacies was one of the most intellectually challenging projects Raymond has taken on as biographer, she said, and that also made him one of her favorites.

“Davis developed a somewhat paradoxical ‘daring and deferential’ persona that helped him become one of America’s first crossover stars and facilitated his success as an unconventional civil rights activist who desegregated public spaces, served as a spokesperson for the movement, and raised enough money to help keep key organizations afloat,” she said. “In the 1950s and 1960s, celebrities risked sabotaging their mainstream success with such controversial political causes.”

Yet Davis’ deferential side also made him vulnerable to accusations of racial accommodationism throughout his career, charges that never allowed him to be thought of as an activist, Raymond said.

“Part of what made him so fascinating was discovering all of the fundraisers, benefits and other civil rights rallies he headlined, and realizing the sheer amount of money he raised,” she said. “Sifting through archival footage of his television appearances and nightclub performances was also a pleasure because he was enormously talented, and really, really funny.”

The documentary, which had its world premiere at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival, was shown at a number of film festivals, including DOC NYC. The film garnered multiple awards, including the Jury Prize and Audience Award for Best Documentary Feature at the Pan African Film & Arts Festival, the Audience Award at the Nashville Film Festival 2018 and Best Documentary Feature at the Louisiana International Film Festival.

Raymond said she hopes the film gives viewers an appreciation of Davis’ “versatility as a performer, especially in front of live audiences, the likes of which we may never see again, and for the emotional price he paid by tackling racial obstacles that negatively affected our nation.”

“While it is true that Davis won fame in part because he was revolutionary — he did things no performer had done before, like imitate white celebrities and kiss a white woman on a Broadway stage — it is also true that because of him, what was then revolutionary is now commonplace,” she said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.