Aug. 3, 2021

‘A painful chapter in our nation’s history’: New class to shed light on Indigenous boarding schools

Share this story

Cristina Stanciu, Ph.D., director of the Humanities Research Center at Virginia Commonwealth University, applauds Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland for starting the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative this summer to review the troubled past of federal boarding school policies, a topic Stanciu has been studying for 15 years.

Haaland started the initiative, which will be overseen by the assistant secretary for Indian affairs, in response to the discovery by Canada’s Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc First Nation of 215 unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. The New York Times reported this summer that the remains of as many as 751 people, mainly children, had also been found in unmarked graves on the site of a former boarding school in Saskatchewan.

Stanciu, an associate professor of English in the VCU College of Humanities and Sciences, will shed light on Indigenous boarding schools in her new course, The Literature of Indigenous Boarding Schools (English 358), starting this fall. It is the first course at VCU on the subject.

The class will spotlight the history and representation of the boarding schools, which aimed to assimilate Native American children and destroy Indigenous cultures and communities. The United States began establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation starting with the Civilization Fund Act of 1819.

According to Stanciu, some of the most harmful institutions of so-called Native American “education” were off-reservation boarding schools such as Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. It was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. Several Native American students from the school have contributed written accounts to various publications.

While the focus of the VCU course will be on Native American boarding and residential schools supported by the federal governments of the United States and Canada, it will also include Aboriginal students’ experiences in other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand.

“This is a great opportunity to teach history through literature,” Stanciu said. “You can’t really teach Indigenous literature without Indigenous history.”

‘A little-known chapter in American history’

Over the past 150 years, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children in the U.S. were taken from their communities to be educated in boarding schools, according to Haaland.

“This is a little-known chapter in American history,” Stanciu said. “It is important to talk about what it meant to take these Native [American] children from their parents and Native communities during their formative years, and to send them away to these schools where they lost connections with their cultures, languages and their reservations for years. It is also important to understand the intergenerational trauma the removal of children has produced in Native communities, and the impact it still has on entire generations of Native writers.

“In European and white American contexts, boarding schools were typically sites for educating the children of the elites; federal U.S. boarding schools were arenas of governmental power and control over Native students’ minds and bodies,” Stanciu said. “Native children, sometimes as young as 5, were taken away from their families, sometimes by force, for months or years, and many never made it back home.”

Stanciu’s course will take an in-depth look at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and other federal Indian boarding schools. The idea of removing Native American children from their communities and taking them away from their ancestral lands originated with Richard Henry Pratt, Carlisle’s founder, she said.

“Pratt emphatically called for the complete immersion of Native students into white society,” said Stanciu, who is working on a book about the literature of Indigenous boarding schools. “His Americanization mantra was, ‘kill the Indian and save the man,’ similar to the mission of Canadian residential schools, which aimed to ‘kill the Indian in the child.’”

Stanciu has written about what she calls “this experiment in Americanization” in another book, “The Makings and Unmakings of Americans: Indians and Immigrants in American Literature and Culture, 1879-1924,” forthcoming next year from Yale University Press.

“This is a little-known chapter in American history. It is important to talk about what it meant to take these Native [American] children from their parents and Native communities during their formative years, and to send them away to these schools where they lost connections with their cultures, languages and their reservations for years.”

Cristina Stanciu, Ph.D.

An immersive experience

Besides visits to local reservations, Stanciu will encourage her students to attend the Pocahontas Reframed Film Festival at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Nov. 19-21. One film to be screened at the festival is a documentary about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, “Home from School: The Children of Carlisle.”

“There will be an opportunity to speak with Native people from Virginia and across the United States and Canada at Pocahontas Reframed, which is being held during a month honoring the heritage of American Indians and Alaska Natives,” Stanciu said. “It will be an immersion in this topic.”

The students in Stanciu’s class will also have an opportunity to join a faculty-led group at the Humanities Research Center working on a land acknowledgment project in consultation with local Native American communities, and to participate in the speaker series, which includes several internationally renowned historians of Native America.

“Not many white Americans know about Indigenous history and the survivors of the boarding schools,” she said. “They know even less that these students and their offspring produced an impressive body of work, which both Native and non-Native scholars are beginning to recover, study and teach. We can no longer teach American literature without Indigenous literature.

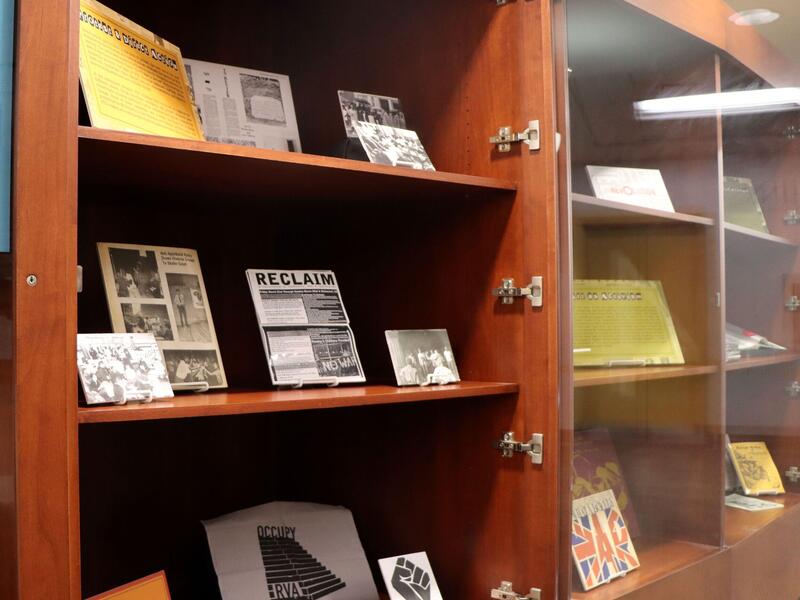

“We are using literature to recover a painful chapter in our nation’s history,” Stanciu said. “This archive of materials we study in this class — from poetry, graphic novels and fiction, to letters the students sent home and articles they published in the school’s newspapers — helps convey this history and offers a glimpse into what the Native children might have felt.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.