Aug. 5, 2021

Is revenge a dish best served cold? For most, ‘hot and ready’ is preferable, VCU study finds

Share this story

While it’s been said that revenge is a dish best served cold, a new study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University found that people are more likely to prefer immediate vengeance.

The study, “Some Revenge Now or More Revenge Later? Applying an Intertemporal Framework to Retaliatory Aggression,” to be published in the journal Motivation Science, involved six experiments with more than 1,500 participants who were given the opportunity to repeatedly choose between a small amount of immediate retaliatory aggression or a larger amount of delayed revenge.

Across the experiments, the researchers found a clear and consistent preference for immediate revenge.

“[Our findings suggest] that people prefer a ‘hot-and-ready’ form of revenge, instead of a cold, calculated and delayed approach to vengeance,” said David Chester, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Psychology in the College of Humanities and Sciences and director of VCU’s Social Psychology and Neuroscience Lab, which seeks to understand why people try to harm one another.

The researchers found that while participants preferred immediate revenge overall, it was also possible to shift that preference. When the participants were instructed to ruminate on a past provocation, they began to prefer delayed-but-greater revenge over immediate-but-lesser revenge.

“We were able to shift participant preferences toward the delayed-but-greater choices using various experimental provocations,” said Samuel West, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow with the Injury and Violence Prevention Program at VCU Health. “Participants also exhibited this preference when we asked them to think about someone from their actual life that had hurt them to serve as a hypothetical target. Even though our participants knew that their choices wouldn’t actually result in harm to their chosen target, strong differences in these preferences were reliably observed.”

In one experiment, participants were invited to play a video game against what they thought was a real opponent. They were told they could choose to subject their opponent to a lesser noise blast that would be played through their headphones, or wait to inflict a louder noise blast the next day at a follow-up session.

In another, participants were asked to interact with two others in a virtual chat room, but were then intentionally excluded from 80% of the conversation. The participant then had the opportunity to choose how long one of the offending chat participants would have to submerge their hand in painfully cold water.

Overall, the researchers said, the findings paint a picture that most people prefer immediate retaliation, but preferences for delayed revenge can emerge among those who focus on past wrongs and those with a predisposition to inflicting harm.

“Participants in our studies who displayed a preference for delayed-but-greater revenge were more willing to wait for their desired revenge than they were monetary rewards,” West said. “In other words, revenge held its value for a longer period of time than did money to these participants. Across all of our studies we found that these preferences were highly divisive, such that 42% of participants were more willing to wait to enact more severe vengeance. Making this more complex is the fact that we also found that such individuals also had greater antagonistic traits like sadism (i.e., deriving enjoyment out of the suffering of others) and angry rumination.”

The findings make sense, Chester said, as most people consider wrongs done to them require a reasonable, proportionate and immediate retaliatory response to teach provocateurs not to do so again, Chester said.

“Yet when provocations become so severe that we ruminate about them over and over again, or when people provoke the ‘wrong person’ (i.e., a person with antagonistic personality traits), revenge may just become a dish best served cold,” Chester said.

The study is believed to be the first to systematically investigate an intertemporal framework for aggression.

The research could shed new light on contemporary theories of aggression and broader theories of antisocial behavior.

“Human life often entails one provocation after the other. At a certain point, people decide that some antagonisms have crossed the line and are deserving of revenge. Yet how do people decide whether to seek some revenge now or bide their time and inflict more revenge later?” the researchers wrote. “Across six studies, we found that people treated such intertemporal decisions about revenge like they do for other rewards — they preferred receiving some now to receiving more later. In line with major theories of aggression, these preferences were readily shifted by experimental provocation and those with greater antagonistic traits were more willing to wait to deliver a more severe blow.

“Yet our results did not paint those who bided their time for greater revenge as impulsive, uninhibited individuals,” they added. “Instead, they exhibited the recruitment of greater self-regulation.”

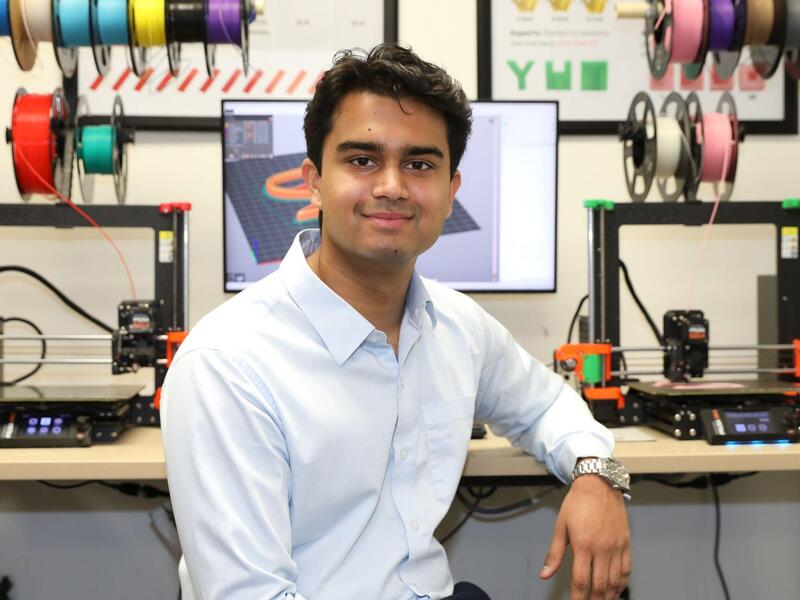

In addition to West and Chester, the study’s authors include VCU alum Emily Lasko, Ph.D.; Calvin Hall, a VCU psychology doctoral student; and Nayaab Khan, a recent graduate of VCU’s undergraduate psychology program.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.