Nov. 16, 2021

The lasting effects of exclusion and segregation for Black Americans in Northern Virginia

Share this story

A new report from the Northern Virginia Health Foundation and the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University recounts the long history of exclusion and segregation in Northern Virginia, which has harmed the health of residents of some communities and concentrated wealth and opportunity for others, a process that has occurred over generations and continues today.

The research provides a “backstory” to a 2017 VCU study for the foundation that documented a 17-year gap in life expectancy across Northern Virginia, an area known for its affluence and quality of life. The 2017 study identified 15 “islands of disadvantage,” clusters of census tracts where residents — disproportionately people of color — face living conditions, such as poverty, low levels of education, lack of affordable housing and inadequate access to health care, that take years off their lives.

“Deeply Rooted: History’s Lessons for Equity in Northern Virginia” chronicles Black experiences in Northern Virginia over the past 400 years, based on historical research. The report details a history of exclusion from freedom and home ownership, education, jobs and civil liberties and offers specific suggestions for current policies that could help redress the lasting impact of the past. The report, available at historyfortomorrow.org, explores the history in more detail with stories, videos, photos, news clips and maps.

While the report and website focus on inequities affecting the Black population, similar challenges exist for other communities of color in Northern Virginia, for many of the same reasons.

“Northern Virginia is fortunate to be a prosperous region, but that prosperity is not available to all. The residents of Northern Virginia and their leaders need to understand not only the challenges we face but why we face them,” said Patricia N. Mathews, president of the Northern Virginia Health Foundation. “This report tells the story of how long-standing policies and practices produced the problems we see today and points the way toward solutions for better housing, education, jobs and prosperity for everyone in the region.”

Inequities through the years

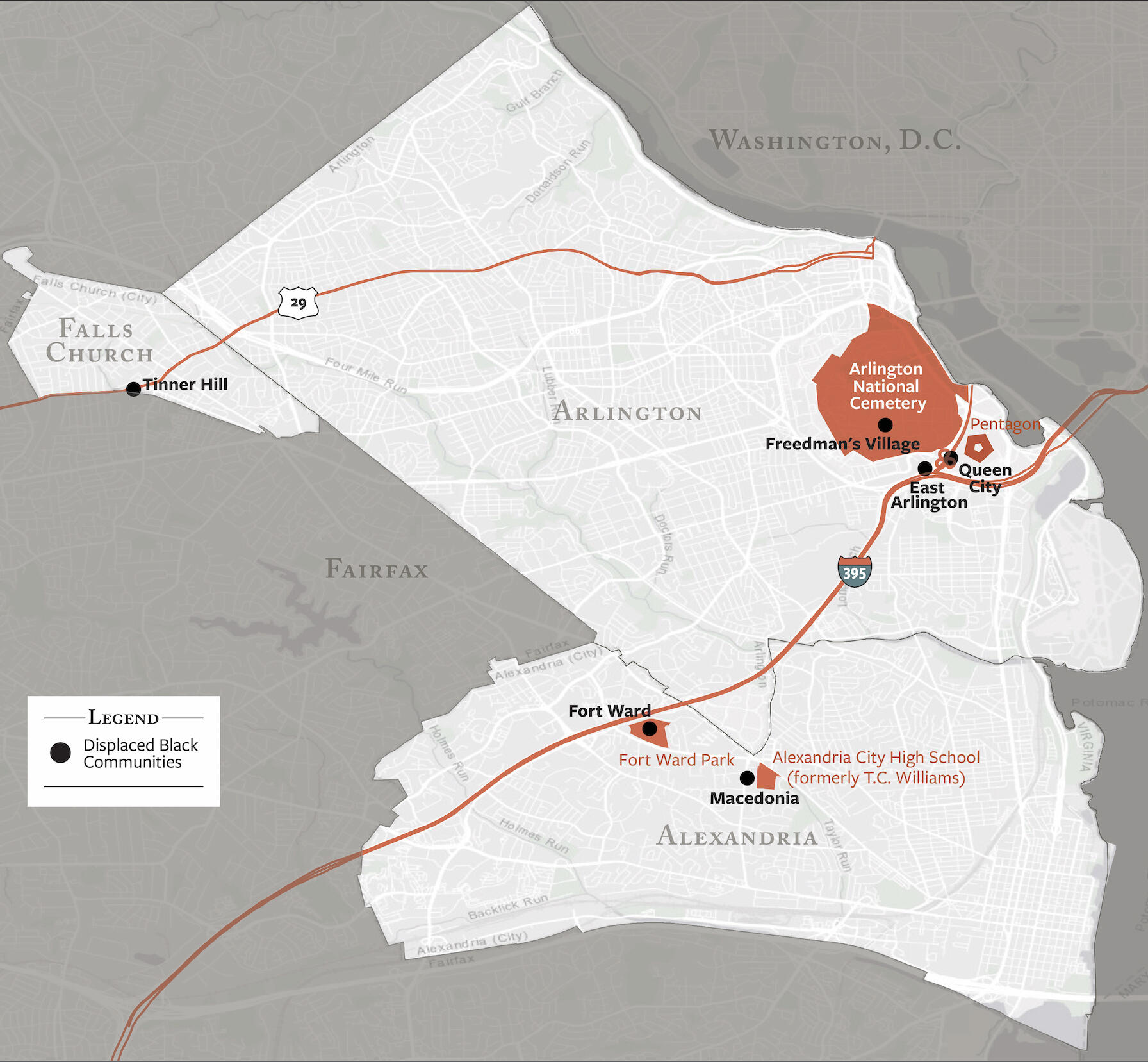

Neighborhood by neighborhood, the report describes how the history of policies and decisions acted over time to shape the health and well-being of communities in Northern Virginia today:

In 1800: More than 40% of Prince William County residents were enslaved; eventually, freed Black people established 19th-century communities such as Batestown and Joplin, which disappeared in the 1930s when the federal government evicted residents to establish a recreational area that became Prince William Forest Park.

In the 1920s: Black families in the enclave of Tinner Hill were displaced when Lee Highway was routed through Falls Church.

In the 1930s: When federally subsidized mortgages became available, they were approved almost exclusively for white buyers and routinely denied to Black buyers. By World War II, suburban development, restrictive covenants that barred Black homeowners and discriminatory lending pushed Arlington’s once widely dispersed Black population into three small enclaves.

In 1942: The federal government invoked eminent domain and razed two Black communities, East Arlington and Queen City, to build roads leading to the Pentagon.

In the 1950s and 1960s: Suburban development displaced Black families in the Fort Ward and Seminary communities of Alexandria; the largely Black village of Willard in Loudoun County was razed to build Washington-Dulles International Airport.

In the 1960s and 1970s: People of color came to represent a larger share of the population along Shirley Memorial Highway and Interstate 95, occupying the communities of West Alexandria (Shirley-Duke, Beauregard) and the subdivisions that were built along Interstate 95 in Prince William County between Woodbridge and Dumfries, where Northern Virginia’s largest Black populations are now located.

“The disadvantaged neighborhoods we see today did not come about by accident — decades of policies have served to segregate people of color and choke off opportunities for education and wealth building, making a downhill economic spiral inevitable,” said Steven Woolf, M.D., director emeritus of the VCU Center on Society and Health and lead author of the report. “This history includes story after story of the resilience and determination of the Black families of Northern Virginia to fight for civil rights and build a better future for their children.”

The Center on Society and Health’s mission is to answer relevant questions that can move the needle to improve the health of Americans by presenting work that is useful to decision-makers. The report provides policymakers and community leaders with a chance to create change that benefits all Virginians.

“The good news is that if policies got us here, policies can get us out,” Woolf said. “Being intentional today about opening doors of opportunity for Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Asian American and other immigrants is good for our region, can strengthen the economy and will help make us whole.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.