Dec. 2, 2021

Class of 2021: Madeleine Dugan digs into art history, Paris at her fingertips

Share this story

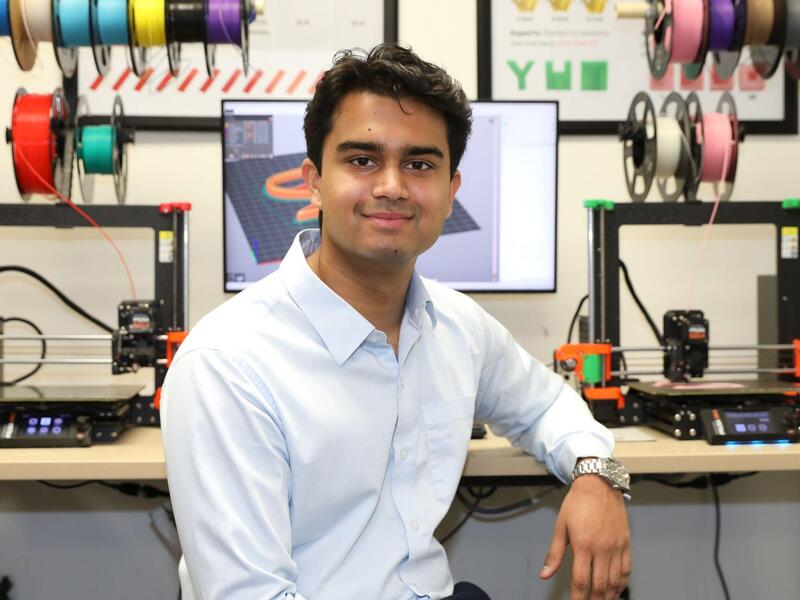

Virginia Commonwealth University art student Madeleine Dugan’s work uncovering facts about the lives of the people in famed photographer Man Ray’s portraits played a key role in creating the exhibition “Man Ray: The Paris Years,” on view at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts through Feb. 21.

When Dugan graduates in December, she will have the unique credential of “exhibition research assistant” on her resume and can tout having a strong imprint on a groundbreaking exhibit that shines a light on those who worked, lived and performed in Paris in the 1920s and 30s.

“I really have loved it a lot,” said Dugan, who is majoring in craft and material design in the School of the Arts and minoring in art history and criminal justice. “I like making discoveries, and researching is so fun. I just love to learn.”

Sarah Powers, Ph.D., a VMFA curatorial research specialist who was Dugan’s high school art history teacher at St. Catherine’s School, gave her the tip about the job opportunity two years ago. Powers is married to Michael Taylor, Ph.D., chief curator and deputy director for art and education at the VMFA. Once in the job, Dugan worked directly with Taylor, who included her in meetings organizing the show, always asking her opinion on plans from design to programming. Dugan had a key role in other tasks from writing labels to proofreading copy.

“There were wonderful discussions around cultural appropriation [in Man Ray’s photographs],” Taylor said. “Madeleine brought so much to the fore and I think that’s what's been great about this is that the exhibition is unlike any previous Man Ray exhibition.”

“Man Ray: The Paris Years” focuses on the innovative portraits that Man Ray made in the French capital between 1921 and 1940, a time when Paris emerged as a powerful center of artistic freedom and daring experimentation. Shortly after his arrival in July 1921, Man Ray started documenting the international avant-garde in Paris in a series of portraits that established his reputation as one of the leading Surrealist photographers of his era.

“His photographs do not look like those of other photographers,” Taylor said. “He had a special way of working where he would make a contact print and he would basically crop out all the extraneous details and then he would blow it up. So people say the sitters are bursting out of the frame. And when you do that, it also softens the features and gives them a glow.”

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890, Man Ray was 30 years old when he arrived in Paris. Dugan views him, and his contemporaries, as young artists exploring their boundaries, much like her peers.

“They were just some young guys who wanted to mess with people,” Dugan said. “They were making revolutionary images to make themselves laugh that didn't have to make sense. I think that's a cool form of art.”

With photos from the VMFA’s collection, photos on loan, auxiliary materials and research, Dugan and Taylor made discoveries about Man Ray and the lesser-known or forgotten people in his portraits. They are satisfied with the portrayal of the artist in a less heroic light than in previous exhibits. Taylor and Dugan aimed to convey the dialogue between Man Ray and the people in his photographs.

A fuller portrait of the modern woman

Dugan dug into the stories of people like Simone Breton, the tragic love interest of poet Andre Breton, her ex-husband.

“And it's like, ‘No, she owned a gallery. She was an artist. It's like, there's so much more to women than that,’ Dugan said.

In the exhibit, viewers will see women in the 1920s who had their own ideas, such as Alice Prin, an actress, painter and nightclub performer who acquired the nickname Kiki de Montparnasse from the Paris neighborhood Montparnasse, where she was performed.

“We hit gold when we were starting to tell the stories of the people whose story is never told,” Taylor said.

To develop and tell those stories, Dugan went through what Taylor calls a process of discovery, establishing a chronology and themes. That also influenced the exhibit design.

“Michael would give me 10 questions about 10 different portraits a week and I would research them either in the VCU library or just on my computer,” Dugan said. “Once we had gotten through the research phase, that's when we started doing design and we'd meet the design team. We went through the magazines where Man Ray published his work. We learned a lot, but we also helped design the exhibit and pick colors for the gallery, which is based off of the magazines that we were looking at.”

That included making a lot of spreadsheets for maps of the galleries and planning where portraits were going to be arranged by printing out pictures of every single photo in the show and grouping them on tables. They arranged by groups asking: “Who goes with who?”

“I did a lot of eBay shopping,” Dugan said. “I found a lot of magazines [that are in the show] that Man Ray published photos in.”

Magazines were largely how Man Ray made his mark. To find that work, Dugan searched for hours for magazines with Man Ray’s colorized photos of American socialite Wallis Simpson. Dugan found a 1934 Time magazine with a cover image of British writer Virginia Woolf on eBay that is included in the exhibit as well.

EBay was also useful to locate vinyl records by Ruby Richards, who performed at the Cotton Club in New York, then the Folies Bergère in Paris.

“I recorded Richards’ record in the VCU lab, in the basement of the library because we have a record player, and that's what you hear in the gallery devoted to Ruby Richards,” Dugan said.

Richard’s life was hard to document as she slipped into obscurity. Dugan’s research on Ancestry.com paid off when she discovered Richards’ 1940 census record on someone's tree.

“I clicked on that tree and it was huge. And I was like: ‘Wait, Ruby Richards is related to people?’ Well, obviously. But you know, I couldn't find most people's family trees. They're not complete at all. I had to make them from scratch, but with Ruby Richards, someone had already been making it.”

Dugan messaged the person, who turned out to be Richards’ great niece, who could fill in more information about the singer. Dugan was able to include photos and magazines from the family’s collection documenting Richards’ full life and accomplishments that pushed boundaries at the time.

“It was really cool,” Dugan said. “It was just awesome. Ruby Richards’ great niece gave me a hug at the opening of the exhibit.”

Amazing discoveries

Taylor said Dugan’s discoveries added “meat to the bones” of missing knowledge about Man Ray’s life and the people he photographed. The chronology in the exhibit and in the 320-page exhibition catalogue is more comprehensive than other portrayals of Man Ray because of the efforts by Dugan and Taylor. The pair focused on verifying dates and places of photographs and events to develop fuller biographies and chronologies of the many women photographed in the show who are usually a footnote or mischaracterized as other artists’ muses or girlfriends.

Dugan’s findings also add depth to an exhibit that paints a picture of the lives of the many people of color Man Ray photographed as well as Dadaists, Surrealists and members of the international avant-garde. Many, like Man Ray, who was Jewish, had to ultimately flee Europe as the Nazis rose to power. Several people in the portraits at the VMFA exhibit were killed in the Holocaust.

Dugan credits her ability to sleuth out the needed information because of a foundation laid by Cooper but also coursework at VCU.

“My UNIV 200 professor broke it up into different sections where we learned how to research and use the databases in the library really well,” Dugan said. “So I knew how to use the VCU library like that. And that's why it was really easy when Michael [Taylor] was like: ‘Find this quote in a random book.’ I would be in the stacks and find it really fast.”

The VMFA occupies a special place in Dugan’s heart. Visiting once as a child, she wandered off from her mother. She distinctly remembers ending up in a gallery of Degas paintings and sculptures.

Her own art is generally three-dimensional, though Dugan started as a painter. Her minor in criminal justice stems from her interest in true crime. She thought she would go into forensic facial reconstruction. Now she’s not so sure. The experience researching the Man Ray exhibition has changed that. When she graduates, Dugan thinks she would like to keep making art while also continuing with museum work.

“Being paid to learn all the time is amazing,” Dugan said. “It’s so rewarding. Being able to give back to people whose memories have been completely lost, especially women, has been empowering for me.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.