Dec. 15, 2021

VCU lab testing delta-8 products finds misleading labeling, lack of safety standards

Share this story

A Virginia Commonwealth University lab has been analyzing products made with the newly popular delta-8 THC cannabis analog available in most CBD and tobacco retail outlets. They have found an alarming lack of safety standards, accurate labeling and quality control.

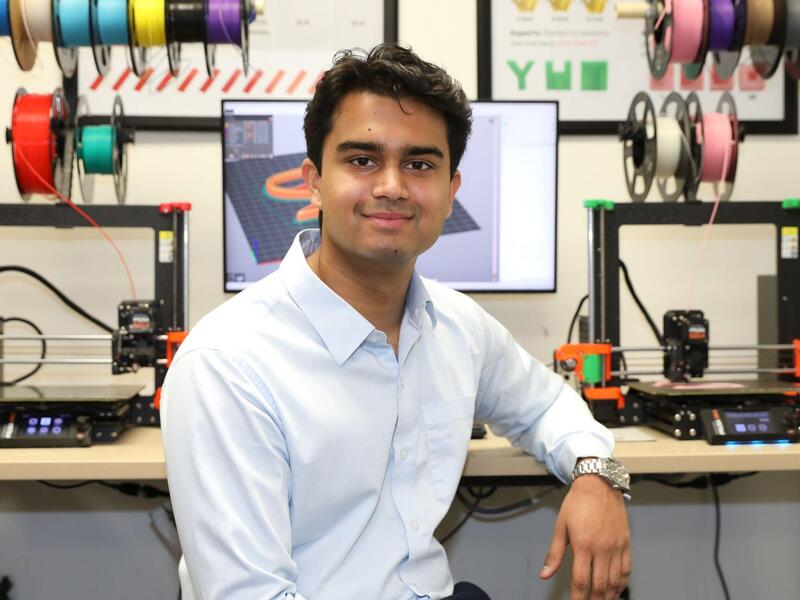

Since early in the summer, the lab of Michelle Peace, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Forensic Science in the College of Humanities and Sciences, has tested dozens of products sold in Virginia that contain delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol, or delta-8 THC, a psychoactive cannabinoid that can have psychoactive and intoxicating effects similar to those of delta-9 THC, the main compound in cannabis.

“What we know — and we have analyzed lots of products — is that there’s no quality assurance for the final product,” Peace said. “We know, for instance, that in some of the products we have evaluated, they are two, three, 10 times more concentrated with delta-8 than what the package claims. That can create, potentially, a pretty scary experience for the consumer, particularly if they are inexperienced.”

Products made with delta-8, as well as other synthetic cannabinoids such as delta-10, THCP and THC-O, have entered the market, often touted as a legal alternative to cannabis. These products are technically not legal because they contain a synthetic cannabinoid and include smokeable flower, oils and edibles, including gummies, cereal bars, cookies and more. Adult-use cannabis is projected to be available for legal retail sales in Virginia in 2024.

Delta-8 products are made by cooking CBD in a strong acid over several days and then extracting with ether. The process creates delta-8 THC and delta-9 THC. Products sold containing delta-8 actually contain synthetic delta-8 THC, which is federally illegal. Additionally, CBD and CBD-derived products often include a certificate of analysis that leads people to believe it is regulated and safe. These certificates, Peace’s lab has found, are often misleading or incorrect.

Regulated and quality tested CBD products in Virginia are only available through the commonwealth’s medical marijuana program and attainable at a dispensary. All other CBD products are not regulated, and therefore, consumers have no way of knowing which products are safe to consume. The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services oversees and regulates the production of hemp, which is used to manufacture CBD products.

However, Peace said, the agency has not put forth regulations to govern the quality of consumable hemp/CBD products like flower and edibles that are manufactured outside the medical marijuana program. The agency, she added, does not have the resources and personnel to monitor the quality of CBD or CBD-derived products.

“What we have demonstrated, time and again, is that very few certificates of analysis for CBD products are correct,” she said. “We know that in some labs nationwide, they never even opened the package that’s sent to them. They just make up the [certificate of analysis] or copy it from another product. Oftentimes, the QR code on a product label takes you to the certificate of an entirely different product. Labs should be required to be properly accredited, and the entire cannabis ecosystem should be required to be transparent.

“At the end of the day, it's a consumer safety issue,” Peace said. “For the most part, people are not aware of what they're buying and cannot make informed decisions about what they consume.”

Developing better identification methods

On a recent afternoon in Peace’s lab, Amanda Moses Ferreira used a scalpel to remove a tiny sample of a Cinnamon Toast Crunch treat drizzled with a glaze believed to contain synthetically produced delta-8. Ferreira, a scientific officer in the chemistry department of a forensic science lab in Trinidad and Tobago, has been analyzing samples at VCU as part of a Hubert H. Humphrey Fellowship to learn about technical methods for identifying emerging psychoactive substances.

“With the decriminalization of cannabis [in Trinidad and Tobago], we are starting to see a lot more edibles and seeing people move more into using cannabis in other forms, including e-cigarettes or e-liquids,” she said. “And I know that we've been seeing a lot more cases of the schoolchildren using these types of products.”

What we have demonstrated, time and again, is that very few certificates of analysis for CBD products are correct. We know that in some labs nationwide, they never even opened the package that’s sent to them. They just make up the [certificate of analysis] or copy it from another product.

Michelle Peace

Ferreira and Peace have been researching ways for drug testing labs to better identify delta-8 and other cannabis analogs.

“What's very interesting about delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol and delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is that they are only different by the placement of one double bond. Delta-9 THC is the most abundant psychoactive cannabinoid in the cannabis sativa plant. Delta-8 THC is also naturally in the plant, but in trace amounts. The delta-8 in products is synthetic because you cannot extract enough delta-8 from the plant to be in the concentrations in the products we are seeing,” Peace said. “From an analytical perspective, delta-8 originally looked like a contaminant when looking for delta-9. We knew that this was posing a significant challenge for drug testing labs.”

Peace’s lab is preparing to publish research that outlines methods for drug testing labs to separate and better identify delta-8 and delta-9.

“From the analytical and pharmacological perspectives, there are a lot of questions that need to be answered,” Peace said.

‘Consumers don’t know what they’re getting’

A number of the samples tested in Peace’s lab have been purchased from Richmond-area retail shops. Other samples have been sent in, including from a recent poisoning case in Roanoke where a 2-year-old was hospitalized after eating a delta-8 product resembling Apple Jacks cereal.

In another case, Peace’s lab was sent samples found in the dwelling of a person who committed a crime while experiencing severe hallucinations. One of the products, which had been opened and presumably consumed, was made with THC-O, a cannabinoid believed to be 300 times more hallucinogenic than THC.

“This person was a cannabis user and went to a local CBD shop to purchase new product. The shop owner said, ‘You should try this,’” Peace said. “People believe, when they walk into a shop, that they're being informed correctly. So he goes home and takes this product with a new analog — a new synthetic cannabinoid. … That’s the problem. Consumers don’t know what they’re getting. And particularly if they’re inexperienced, they might have an effect they’re not expecting, is terrifying, or is dangerous.”

The research into delta-8 and other emerging cannabinoids builds on Peace’s years of research into substance use trends with novel psychoactive substances, legal drugs and over-the-counter medications.

Included among her projects are research into the efficacy of electronic cigarettes as an illicit drug delivery system. Another is exploring the implications of the fact that e-liquids — the flavored nicotine solution used in e-cigarettes — often contain the unlisted ingredient ethanol, or alcohol.

In the case of e-cigarettes and cannabis products, Peace says a common thread is that a lack of consistent safety standards, accurate ingredient lists and quality control in labs raises major consumer safety concerns.

“There’s little transparency and there’s zero federal oversight,” she said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.