Feb. 28, 2022

VCU professor’s new book challenges ageism in society

Share this story

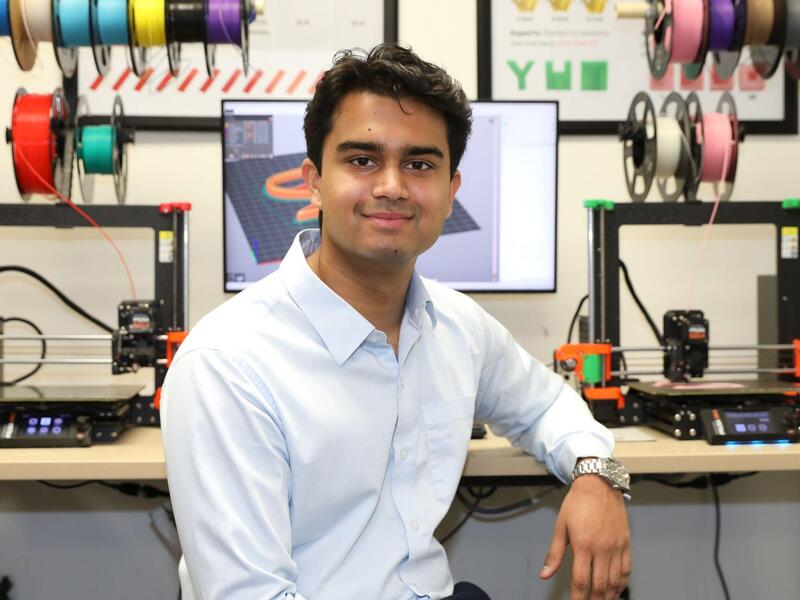

In her book "Ageism Unmasked: Exploring Age Bias and How to End It," Tracey Gendron, Ph.D., director of the Virginia Center on Aging at Virginia Commonwealth University, challenges why “everything we know about aging is wrong,” and why the concept of generations divides us more than it serves to bring us together.

“Ageism is pervasive, ubiquitous and invisible,” said Gendron, chair of the Department of Gerontology in the VCU College of Health Professions. “It's so normalized that we literally have to unmask ourselves to be able to see it because it's all around us and it's been all around us for decades. Ageism affects your health, happiness, longevity and wellness.”

Gendron and VCU’s gerontology faculty have spent years working to dismantle societal misconceptions about aging that often lead to ageism. Gendron co-led efforts that led to VCU earning a designation last year as Virginia’s only university to join the Age-Friendly University Global Network.

Gendron’s interest in gerontology started with a high school psychology class and was influenced by her close relationship with her grandparents, whose experience in elderhood she discusses in her book.

Ageism is a systemic problem that reared its head during the pandemic, Gendron said. Ahead of the book’s release on Tuesday and a book signing at VCU College of Health Professions later in March, VCU News asked Gendron about ageism during the pandemic, ageism at work and what to enjoy and look forward to about the experience of elderhood.

How did the pandemic affect ageism behavior?

At the beginning, in March and April 2020, I started to see a lot of examples of ageist sentiment and ageism behavior. “This is just an old person's disease” was all over the news. There was an attitude like, “Why should we care? We should sacrifice older adults for the sake of the economy, because why are they important anyway?” But there were also attitudes like, “Let's blame young people and call them millennials, even though they weren't millennials, for not adhering to masking guidelines.” It was all of this ageism and generational rhetoric.

It was harsh. There was a hashtag #BoomerRemover. It was floating around social media. It was like an upgrade from #OkayBoomer. It was just nonchalantly asking, “Why should we care about older people? They don't contribute anything.” Which couldn't be further from the truth. It was institutional. Long-term care and nursing homes were some of the hardest-hit places, and it wasn't just the residents living there. It was the staff members as well.

We were talking about direct care and hospital staff being heroes, making sure that they had the personal protective equipment that they needed, that they were protected. But nobody was talking about long-term care staff as heroes. So, if you're not valuing the people that work to support older adults, it's another way of devaluing older adults themselves. It was structural ageism.

You write about the misperception that older adults are considered expensive to employ. Can you elaborate?

We don't value the wisdom and experience that older adults bring. The whole system of retirement was developed to move older people out of the workforce to pay younger people less money. That's why pensions, retirement and Social Security came about. We've institutionalized that system. But back then [when these programs were started in the early part of the 20th century], people didn't live until their 80s, 90s and 100. And now they do. And people don't necessarily want to stop working at any given age because people find meaning and purpose from their work. If we had age-inclusive, intergenerational workspaces, where it was welcoming for people to learn from each other, wouldn't that be kind of cool?

Your book discusses ageism and ableism in the workplace. How has this changed over time to form the attitudes around aging many people hold today?

After the Industrial Revolution, we started to value mobility. People were leaving their family farms and their family areas in order to move to cities for jobs. The places where we were working and living became separate. That was truly a turning point when it comes to attitudes about aging. You started to see the families change in shape and form. So that was one factor in the workplace. We started to value more productivity. And you started to see some sentiments that older workers were doing things the old way and that they couldn't keep up with the new way of doing things.

At the same time, we also started to socially construct childhood to more of how it looks today. Instead of having children work on the farms as they used to do as active contributors, childhood became this protected period of time for children to develop and be nurtured and grow. Caring for children became something that was expected, that came with great rewards and great challenges. But a byproduct was that we started to see caring for elders as something different, more of a burden. We started to institutionalize, to create these nursing facilities that would house older people.

What suggestions do you offer in the book regarding ageism?

I give opportunities to reframe our thinking about how we see ourselves and the language that we use. How do we talk about being old? How do we talk about being young? I challenge some of the labels that we use, especially the generational labels, to get people to ask themselves questions, to choose for themselves.

The anti-aging industry is another topic I focus on to ask people to think about how they define success and beauty. People need to ask themselves if they are letting an industry or somebody else define it for them. If you want to use anti-aging products, be my guest. If you want to dye your hair, be my guest. If you want to have a procedure, be my guest. But are you doing it in shame? Are you doing it because marketers have told you that that's what is beautiful? What I'm trying to do in the book is empower people to make their own choices and be led by their own vision of what is successful for them.

You’ve shared that the last chapter of your book on elderhood is particularly powerful. Can you tell us more about this? What should people know about elderhood?

We talk about infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood and then it's just older adulthood. It's like this nebulous period that just goes on and on for 40 or 50 years. I think elderhood is important because it's a unique and distinct stage of life that offers different opportunities for growth and development. Elderhood to me is focused on a unique stage of life that is different from adulthood and involves positive growth, whereas when we talk about “older adulthood” – we think about it in more of a decline-only based way.

The last chapter of the book talks about how we can challenge our bias. We can envision our future selves and opportunities for older people. When I think of the age-friendly movement, it means age inclusive. We need to invest in initiatives that make living within our community accessible and available for everyone. Somebody with a wheelchair as well as someone with a stroller could benefit from sidewalks. We have to address the policy issues and the barriers that exist in order to make age equitable in our policies, in our procedures and in our laws. I think there's a lot of power in that.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.