April 15, 2022

Former Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker explains causes of inflation and its uncertain future

Share this story

The U.S. economy will continue to feel repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic for years.

Most dramatically, consumer prices are up 8.5% over the past year, marking the highest rise in inflation in the country in more than 40 years.

How did we get here? Who’s most affected? Are we heading to a recession?

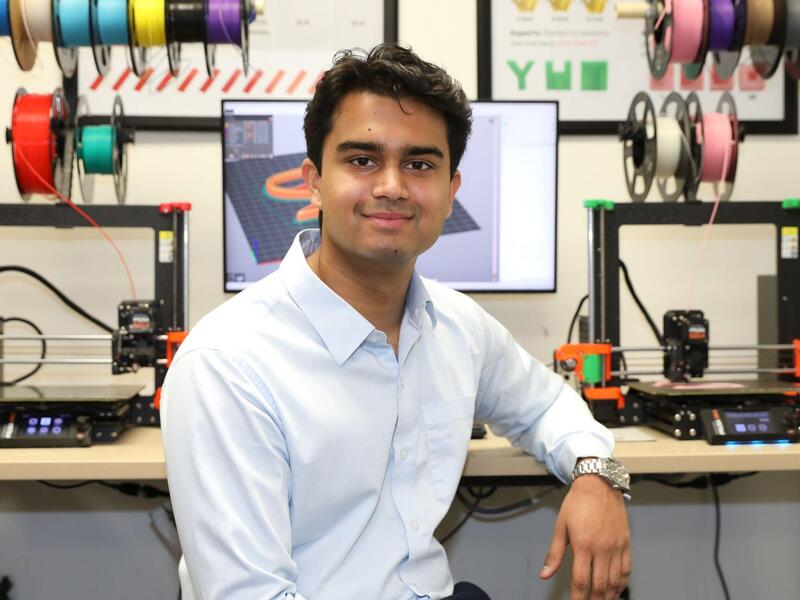

Former Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond President Jeffrey Lacker, a VCU School of Business distinguished professor, discussed the causes and hazy outlook of inflation with VCU News.

What are the main causes of inflation hitting 8.5% — the highest rate in 40-plus years?

Simple sayings are often misleading, but in this case the old adage “too much money chasing too few goods” is right on target. In response to the pandemic and the economic dislocation it caused, Congress passed several bills providing substantial relief payments to American households and businesses. As usual, the recipients did not spend it all at once, but they did spend a sizable amount. Unfortunately, the U.S. economy was incapable of fully satisfying the surge in demand. Many workers have left the labor force, including many that moved up retirement, and they have not returned to the labor force to the extent that some policymakers had hoped. In addition, consumers have shifted spending away from services such as travel, entertainment and restaurants, and toward durable goods. The combination of ramped-up spending and inelastic supply has driven up prices for a range of goods and services. On top of that, workers are understandably seeking and obtaining wage increases to try to make up for inflation. This is putting more upward pressure on costs and inflation.

How much of a role has COVID-19 and the widespread supply chain disruptions played in inflation?

Supply chain disruptions have played a role, in the sense that inflation might not have surged so strongly without them. In some cases, the pandemic has led to factory closings and labor shortages in key sectors, such as transportation. The resulting bottlenecks have hindered the ability to satisfy the surge in demand. But those bottlenecks aren’t the main driver of inflation — in some sense they are more of a symptom than a cause.

Is there a correlation between inflation and unemployment?

Yes, at times there is a correlation — when lower unemployment is associated with higher inflation. This correlation is not stable or reliable, however, and when inflation rises the correlation can break down. This happened in the late 1960s and 1970s, the last time we saw a big surge in inflation — we also saw high unemployment as well.

Who is most affected by the rise in inflation?

Everyone is affected by inflation, but research suggests that lower-income households and those on fixed incomes are hurt the most.

What can and should the Federal Reserve do to mitigate the effects of inflation?

While the main driver of the surge in inflation was the stimulus programs enacted by Congress and the administration, the Federal Reserve has the responsibility and the ability to keep inflation low by raising interest rates. That works by restraining the growth of business and consumer spending and cooling off the labor market. This may be costly to some, and it may involve a recession, but the alternative is an extended period of high and variable inflation, which experience shows would be even more costly in the end.

To counter inflation, the White House unveiled plans to curb the soaring costs of fuel. How much of an impact will this have on inflation?

Efforts to stimulate energy production to dampen rising fuel prices are likely to have only minor effects on the overall rate of inflation in the near term.

How likely is it that we'll see inflation coming back down in the near future? Or are things more likely to get worse first?

When inflation rises it becomes harder to predict. Some components of consumer price indexes seem likely to ease in the near term, such as used car prices. Other components of inflation, such as housing and energy costs, appear likely to remain elevated. And as I mentioned, labor costs are accelerating and much of those increased costs seem likely to be passed on to consumers. While inflation is likely to fluctuate over the next year or two, it appears to have substantial momentum. Over the longer term, inflation is likely to come down as the Fed tightens monetary policy.

What would you like to add?

Another cliché comes to mind, but this one does seem particularly apt right now: The outlook is more uncertain than usual.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.