Jan. 3, 2023

19th-century ‘Connecticut vampire’ receives forensic facial reconstruction with help from VCU researchers

Share this story

Archaeologists in 1990 excavated a 19th-century grave in Griswold, Connecticut, in which the remains were arranged to form a skull and crossbones, indicating that the middle-aged man was thought to be a vampire, possibly because he had tuberculosis. At the time, amid what has been called “The Great New England Vampire Panic,” there was a folklore belief that rearranging skeletal remains would prevent a suspected vampire from returning to life.

For decades, the “Connecticut vampire” was known only as “JB55,” which was spelled out on the coffin’s brass tacks, describing the person’s initials and age at death. In 2019, however, researchers used genealogical DNA methods to identify JB55 as John Barber, who died in the 1830s.

In October, Parabon NanoLabs and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory unveiled a forensic reconstruction of Barber’s face. Virginia Commonwealth University researchers contributed to the project by providing a 3-D digital model of Barber’s skull that helped made the digital reconstruction possible.

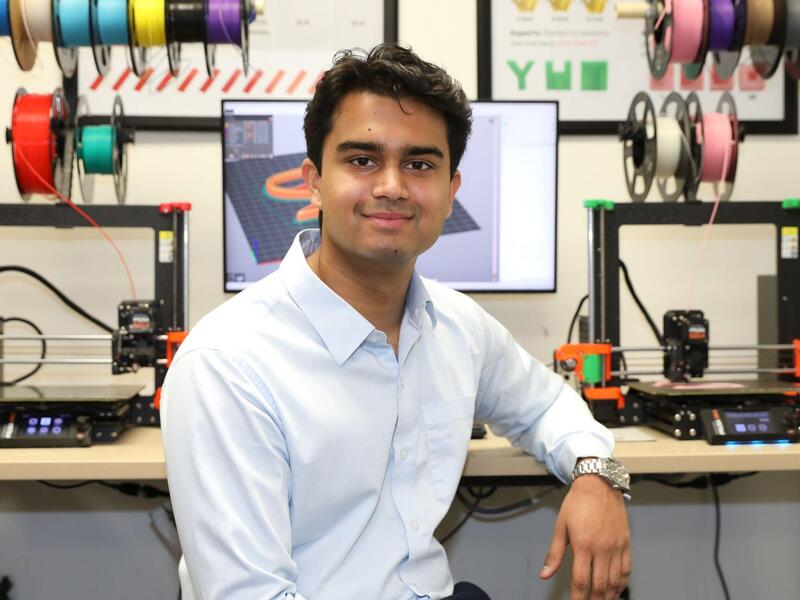

The Virtual Curation Laboratory in the School of World Studies in the VCU College of Humanities and Sciences has a memorandum of understanding with the National Museum of Health and Medicine — where Barber’s remains are held — to 3-D scan injuries and pathologies of human remains, some related to conflict during the Civil War and up to World War I, and others representing interesting cases in the museum’s research collection.

“3-D scanning allows these remains to be shared digitally, including a special collection the VCL maintains through Sketchfab,” said Bernard Means, Ph.D., assistant professor of anthropology and director of the Virtual Curation Lab. “We are assisted in this effort by forensic anthropologist Terrie Simmons-Ehrhardt who is a noted expert in digital applications to recording and sharing forensic case information, both of a historic nature and more recent forensic cases. 3-D scanning the JB55 skull fit directly within this shared mission.”

In the Virtual Curation Lab, Means used a laser 3-D scanner and a structured light scanner to capture the skull, while Simmons-Ehrhardt used photogrammetric software to assemble a 3-D digital model.

“This case allowed us to examine the geometric detail and degree of photorealism that can be captured with 3D surface scanning and photogrammetry and to demonstrate a 3-D workflow for both forensic and historical facial approximation casework,” Simmons-Ehrhardt said.

VCU students Maddie Martin and Emily Pitts, both sophomore anthropology majors, work in the Virtual Curation Lab and contributed to the project by painting 3-D replicas of the skull. Martin’s replica is being provided to the National Museum of Health and Medicine for teaching and public outreach while Pitts’ replica will stay at VCU for similar purposes.

“It was a challenge and took me about a month to complete, but it was fascinating to learn about and be involved with such interesting remains,” Martin said.

Pitts said she was particularly interested in working on the project because of the era’s unusual burial practices for people accused of being vampires.

“Often, methods used in these burial practices give archaeologists insight into existing belief systems and details surrounding the deceased themselves,” Pitts said. “JB55 is a good reflection of the paranoia that his society had revolving [around] sickness and minority actions. A lot of the time people were accused of being vampires due to behaviors that were labeled strange. In JB55’s case, archaeologists attribute his death and subsequent vampire burial to tuberculosis. It is possible that JB55 was deemed a vampire due to his disease, and therefore had to be ‘killed’ by mutilating his corpse.”

Martin added that the project and her work in the Virtual Curation Lab has taught her about the importance of 3-D models and replicas for educating the public.

“Being able to hold and touch an object or manipulate a 3-D scan is invaluable in teaching about and engaging people with history and archaeology,” she said. “I hope to be involved in this more in my future career.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.