March 21, 2023

Digital map of Richmond’s Barton Heights Cemeteries to be unveiled

Share this story

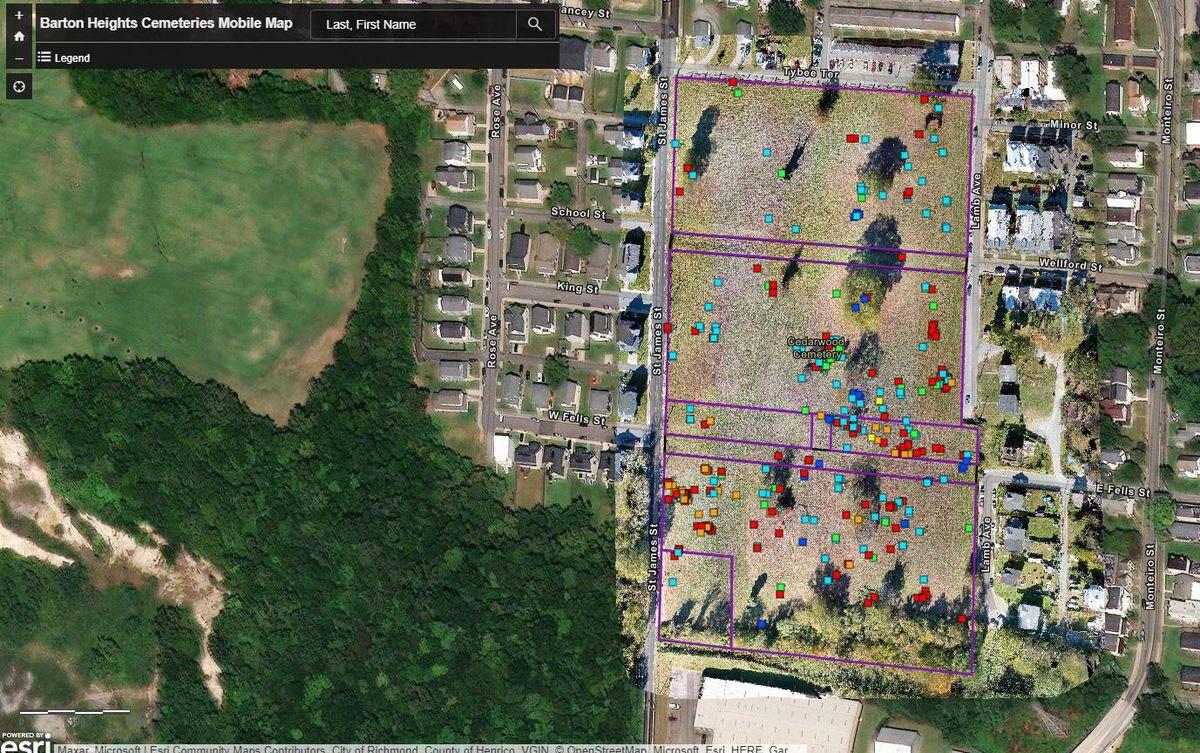

The East End Collaboratory — a collaboration between Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of Richmond, the Friends of East End volunteer group and community partners — has created a digital map of Richmond’s Barton Heights Cemeteries, a 12-acre assemblage of city-owned cemeteries that were originally founded by free African Americans in 1815 and that contain the earliest surviving African American memorials in the Richmond region and possibly all of Virginia.

The map will be unveiled at a community event from 5:30 to 7:45 p.m. on Monday, March 27, at Richmond Public Library’s Main Library, 101 E. Franklin St.

The event, which is open to the public, will highlight the map, along with student projects from VCU and the University of Richmond involving the region’s African American cemeteries and historic landscape. Community representatives from the Descendants Council of Greater Richmond, Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church and the city of Richmond will offer reflections on the work.

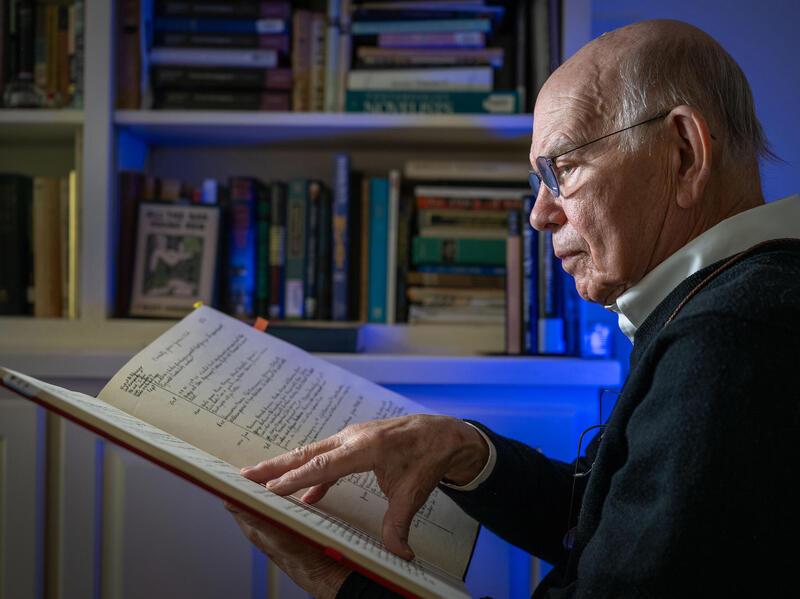

The digital map of the 330 surviving grave markers will provide descendants and others with the ability to much more easily locate markers of those buried at the Barton Heights Cemeteries, which currently lack adequate signage for orientation, said Ryan K. Smith, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of History in the VCU College of Humanities and Sciences and member of the Collaboratory.

“Users can find grave markers by name and by date range, and they can see what other markers or other landmarks are nearby. Users can also use the map to tour the site remotely,” Smith said. “One can navigate across the grounds and stop to see photographs of individual markers in pop-up boxes. Some also have digital three-dimensional scans available for a 360-degree view of the markers.”

Individual markers are linked to the popular Findagrave.com website, which provides historical and biographical information.

“All of this will provide exciting avenues to learn about the lives of free and emancipated African Americans in early Richmond, and it will illustrate artistic and memorial choices made by that community,” Smith said.

An essential but neglected part of Richmond’s history

Loretta Tillman, a member of the Descendants Council of Greater Richmond, said the Barton Heights mapping project is important to Richmond and the descendants of those buried there.

“These six cemeteries, now combined into one, are filled with so many historic figures as well as those less well known, but who were alive during various important eras of United States history to include the Early Republic, the Civil War, Reconstruction and the Civil Rights movement, to name but a few,” she said. “However, because of city neglect of the area, we now know where very few of them are, including several former Black city officials. It is also hard … looking at the surface of the cemeteries to discern how many individuals are in them. The archaeological and historical work done through the project will bring some of them back from the oblivion in which their names and histories now reside and eventually help all Richmonders and those in the wider world to know and appreciate the lives and times of these people.”

As a digital resource, the map may help with conservation and preservation of the markers at Barton Heights, which have experienced vandalism and theft and are threatened by damage from weather. The project could serve as a model for other threatened African American cemeteries, Smith said.

The story of those interred at Barton Heights Cemeteries is an essential but often neglected part of Richmond’s history, Smith said.

“For too long visitors to our region have tended to think only about Hollywood Cemetery, Shockoe Hill Cemetery or St. John’s Churchyard when considering the historic graves of notable cemeteries,” he said.

“The graves at the Barton Heights Cemeteries reveal prosperous African American residents whose life stories undercut simple associations between Black residents and poverty or slavery before the Civil War. Burials at Barton Heights represent leaders across many different fields, including city councilmen, soldiers and militia officers, philanthropists, tradespeople, academics and educators, and pastors. These residents commissioned grave markers from the finest shops available, and their memorials help us understand how Black Richmonders sought to be remembered.”

A collaborative effort of labor, love and community

The East End Collaboratory was formed in 2017 by faculty across disciplines from the University of Richmond and VCU, along with members of the Friends of East End volunteer group. It has since expanded to include the Descendants Council of Greater Richmond, the Woodland Restoration Foundation, and, at various times, Oakwood Arts and the city of Richmond’s Department of Parks, Recreation and Community Facilities.

The Collaboratory previously created a digital map of Richmond’s East End Cemetery, which is the burial site of thousands of African Americans dating back to 1897. That project established something of a template for mapping African American cemeteries in the Richmond region.

The Barton Heights project got underway in 2018 when Collaboratory members started bringing students to the site, accompanied by faculty and staff from the University of Richmond’s Spatial Analysis Lab, which helped guide the mapping effort.

The students carefully surveyed the existing aboveground markers with a GIS app on their smartphones, taking GPS plot points and photographs, along with information like the person’s name, birth and death dates, and inscription text for each marker they encountered.

“After the database was checked and as complete as it could be, we used ArcGIS Online to create a StoryMap that has several links to the public map products,” said Beth Zizzamia, operations manager of the Spatial Analysis Lab and part of the East End Collaboratory. “There’s a simple searchable map for folks at the cemetery wanting to find a particular person. And there’s a more complex dashboard type application that allows a user to select a person based on the last name and death year. The map then updates and shows a nice pop-up with the picture and other collected information.”

Additionally, a drone was flown over Barton Heights to accurately collect the location of each marker, Zizzamia said.

“This project’s story is one of labor, love and community,” Zizzamia said. “It takes so many people, playing their role in a larger network of dedicated folks looking to protect and preserve this special place. I’m in awe when I think about how far this project has come in such a short amount of time.”

Partners in the Barton Heights project include the Descendants Council of Greater Richmond and Richmond’s Parks and Recreation Department, and it was supported by VCU’s Office of Community Engagement and Office of Institutional Equity, Effectiveness and Success, and by the University of Richmond’s Bonner Center for Civic Engagement.

The Descendants Council helped spur the work forward in 2021, Smith said, as their members have lobbied the city for better care of the Barton Heights Cemeteries. They also have accompanied the faculty and students during visits to the site and shared their stories and experiences with the students.

Students play a key role

University of Richmond student Lucien Newton contributed to the project through a class taught by Derek Miller, Ph.D., assistant director, community relationships and community-engaged learning at the Bonner Center for Civic Engagement. Newton helped transcribe death records to make them accessible to descendants and others online.

“I think that the project is a good thing and shows positive efforts being made between archaeologists (and other professionals) and descendant communities,” he said. “It shows that state institutions in positions of power are becoming more committed to playing a role in positive social change and are aware of the troubles that the surrounding community has faced and continues to face. Mapping the cemetery is a good project if it means making the space more available to descendant communities, Richmond as a whole, and even broader communities beyond this. I hope that it will pave the way for similar projects to be done at other cemeteries within the city, and that it will foster a better relationship between community members.”

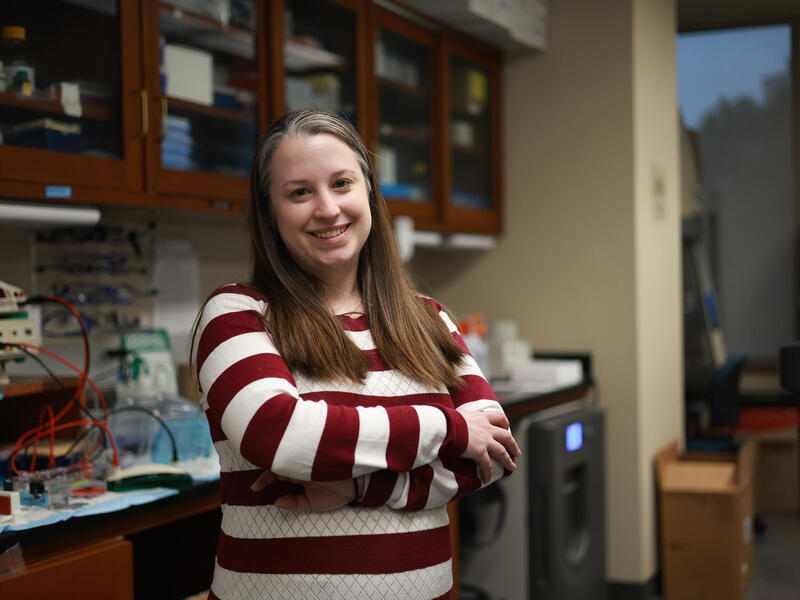

University of Richmond student Gloria Kroodsma and classmates contributed to the field mapping, walking through the cemeteries to ensure that grave markers were recorded and adding data if not.

“A classmate and I brushed away leaves and dirt to reveal a grave marker and found that it was missing a small corner containing the first part of her name — only the last four letters of it remained after 137 years, ‘lett,’” Kroodsma said. “We were glad to be able to record this grave but disappointed that the marker’s state of disrepair could make it harder for descendants or visitors to find. This project was my first exposure to GIS and digital mapping, and it sparked my interest in spatial approaches to archaeology and the sciences.”

Will Teeples, a VCU alum and current student in the Master of Urban and Regional Planning program at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at VCU, served as a GIS technician on the project.

Teeples’ work primarily has involved using mapping resources to record information found on the surviving headstones. Additionally, he has started working as part of a capstone project in partnership with a group of descendants to develop a preservation document that can be used to support the cemeteries in the future.

“This project is meaningful for me because as someone who grew up less than two miles away from the cemetery, I can trace my lineage and ancestry back to the 1800s through maintained cemeteries such as Riverview or Mount Cavalry,” Teeples said. “Those descended from the thousands of freed African Americans buried are not afforded that same luxury. By re-discovering grave markers and depositing names, birth and death years, and grave marker inscriptions I hope to connect surviving descendants with their relatives buried within the cemeteries.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.