Oct. 10, 2023

VCU students’ online story maps highlight the history of Richmond’s Barton Heights and Woodland cemeteries

Share this story

Students in a Virginia Commonwealth University class have created online story map resources about Richmond’s Woodland Cemetery and the Cemeteries of Barton Heights that provide the community with a wealth of information about the historic African American cemeteries drawn from archival research, mapping technology and interviews with descendants.

The class, Sustainable Community Development, part of the Master of Urban and Regional Planning program in the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at VCU, developed the story maps in partnership with descendant and community groups associated with the two cemeteries, including the Descendants Council of Greater Richmond Virginia, the Woodland Restoration Foundation and Friends of East End.

“We wanted to use the story maps as a tool to share the history and importance of Richmond’s African American cemeteries, and by working alongside descendants we were able to learn about and honor people who lived, worked and contributed to this city,” said Meghan Gough, Ph.D., an associate professor of urban and regional studies, who taught the class.

“We hope this project contributes to community dialogue about caring for our collective past,” said Gough, who also co-leads the Cemetery Collaboratory with Ryan K. Smith, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of History in the College of Humanities and Sciences, and two faculty members at the University of Richmond.

Chipping away at systemic silences

Peighton L. Young, co-chair of the Descendants Council of Greater Richmond Virginia and a doctoral candidate at William & Mary, said the story maps address important issues facing both the Cemeteries of Barton Heights and Woodland Cemetery, including “the lack of widespread community support, which is a symptom of the lack of widespread knowledge about these cemeteries, the people buried in them, the descendants of the interred, and cemeteries' significance to the history of Black life and experience in the city of Richmond from the early 19th century through the present-day.”

“These story maps pave the way to rectifying that problem by making the communal, historical and cultural value of these cemeteries accessible to the public,” they said. “In doing so, they begin to chip away the silences created and perpetuated by our city's history of systemic racism towards and the governmental neglect of Richmond's Black community.”

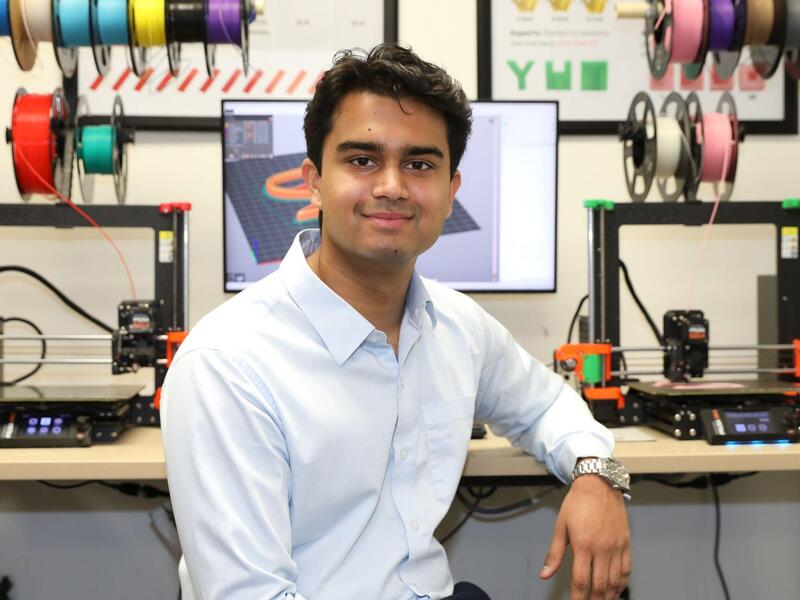

Story maps are online applications that provide maps alongside narrative context and multimedia resources. William Teeples, a student in the class, said these story maps provide a unified resource for descendants to use as a repository for historical information, living history in the form of interviews, photos and biographies, and other resources.

“My hope is that this tool can serve descendants as a tangible asset for them to use to connect with other descendants and tell the stories of the cemeteries they represent,” Teeples said. “The story maps have not only a historical component, but also a narrative component. Both of these cemeteries have been subjected to the whims of prevailing power structures within the city of Richmond, and these story maps analyze the narratives surrounding that throughout their history. In the modern era, individuals representing both the Cemeteries of Barton Heights and Woodland Cemetery have been able to reclaim that narrative through advocacy and volunteer work and it’s important that these efforts don’t go unnoticed.”

Preserving sacred spaces

The Woodland Cemetery story map provides details on the cemetery’s origins, which date to 1891, its layout, a timeline of ownership, an interactive map tour and a section about its changing landscape, detailing how it was overgrown until 2020 when it was purchased by Marvin Harris and the Woodland Restoration Foundation was formed. It also includes a call to action with directions for how to support Woodland with time and labor or donations of funds and resources.

Young’s great-great-great grandfather John Williams Jefferson was born in Amelia County around 1869 to John and Julia Jefferson, who had been born and enslaved in Amelia County until the end of the Civil War. John Jr. moved to Richmond in the late 19th century and worked in a coal yard for several decades, ultimately passing away in 1934. He was buried at Woodland Cemetery, though Young has not been able to locate the grave, possibly because their family either could not afford a marker or because it sank into the ground.

“This project engages the whole of Richmond's community by making knowledge of the histories of these cemeteries accessible,” Young said. “By doing so, they encourage the average person to get involved in preserving some of our city's most sacred places. I think that one of the biggest challenges marginalized communities face while trying to galvanize public support to help them protect their historic sites is the fact that we, as a society, often tend to think of spaces like these as isolated from the rest of our community — and that is never true. This project works to reframe how the public engages with community-based spaces by emphasizing the need for everyone (from long-time city residents to college students) to understand these sites as part of our shared past, our shared history, and our public memory.”

Young added that they hope the project teaches “both students and members of the general public that historical site preservation should not be the sole responsibility of descendants to shoulder. It will take all of us as a community to dismantle the legacies of slavery and systemic racism that have plagued Black residents for generations.”

“For it to be successful, it has to be a community effort. Universities are part of the long-standing communities that they exist within. They do not exist independently of them. I think this project shows that local area college students and university faculty can be involved in supporting the communities they become a part of when they come here. When they do, they can create tangible, substantive change,” Young said.

John Shuck, a board member and volunteer coordinator with the Woodland Restoration Foundation, said the story maps are a valuable resource.

“It kind of gives the overall history of what’s been going on at Woodland,” Shuck said. “I think it’s good to have everything wrapped up at one place in one package.”

Sites of both pain and perseverance

The Cemeteries of Barton Heights story map features sections on the 13-acre site’s history since its founding in 1815, noting how the site’s six cemeteries were among the first in the South owned and operated by free Blacks and African Americans.

“This story map is designed to honor the individuals interred, to raise awareness of the history of the Cemeteries of Barton Heights, and to center historic Black cemeteries as critical components of Richmond's cultural landscape,” the students wrote. “While the history of this space speaks of pain and exclusion, the reclamation of the Cemeteries of Barton Heights illustrates Black resilience, perseverance, and hope.”

The story map describes how Richmond purchased the cemeteries in 1935 and allowed the site to fall into disrepair.

“The city of Richmond and the neighborhood of Barton Heights began an active campaign to abandon this space to memory,” the students wrote. “However, the site perseveres, and though it is largely unidentifiable as a cemetery today, the space holds a collective memory that cannot be overlooked.”

A section on Rediscovery, Celebration and Persistence highlights the cemeteries’ recent history, particularly the advocacy of descendants such as Denise Lester, whose efforts led to the installation of historical markers and state and federal recognition of the site’s history.

Claire Parkey, a student in the class who worked on the project, said she hopes the story maps will support the work of the community and descendant groups to bring more attention to these cemeteries and their history.

“The efforts to desecrate the cemeteries, the intentional, attempted erasure of Black communities, and the enormous amount of work and effort put into the preservation of these spaces are all part of the history of Richmond,” Parkey said. “People need to know about it and understand the celebration of life and persistence represented in the Cemeteries of Barton Heights and Woodland Cemetery.”

Black and African Americans were prevented from keeping written records for much of the city's early history, she added, so it is important to continue talking about these cemeteries and to center the voice of descendants.

“There aren't necessarily books and maps and ephemera to look towards for answers for these spaces; there is instead a rich oral tradition that had been stifled and hushed by numerous efforts to break up Black community in Richmond,” she said. “Storytelling is preservation, is celebration, is resistance in this context, and more than that, it is a reclamation of power. The importance is more complex than this explanation, but this is one significant facet of the project.”

While the students assembled the information, Parkey said, the descendant community was the driving force behind the preservation and storytelling of the cemeteries.

“I hope that people see that not only do these spaces hold grief and pain, they also hold celebration and persistence. These are stories worth preserving, and the spaces deserve the same reverence as places like Hollywood Cemetery,” she said. “Richmond's Black history is more than just pain, and we should preserve spaces that represent joy and accomplishment as well. The historic narrative of the city should reflect that.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.