May 22, 2024

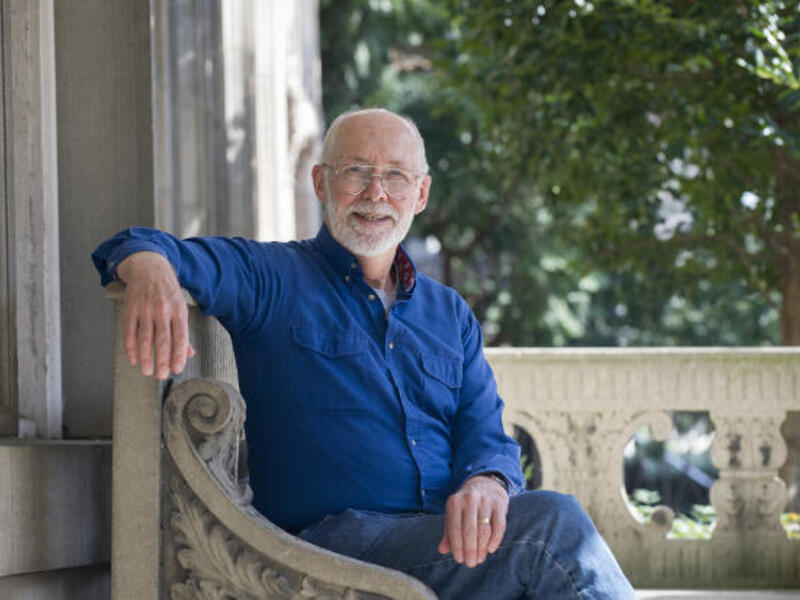

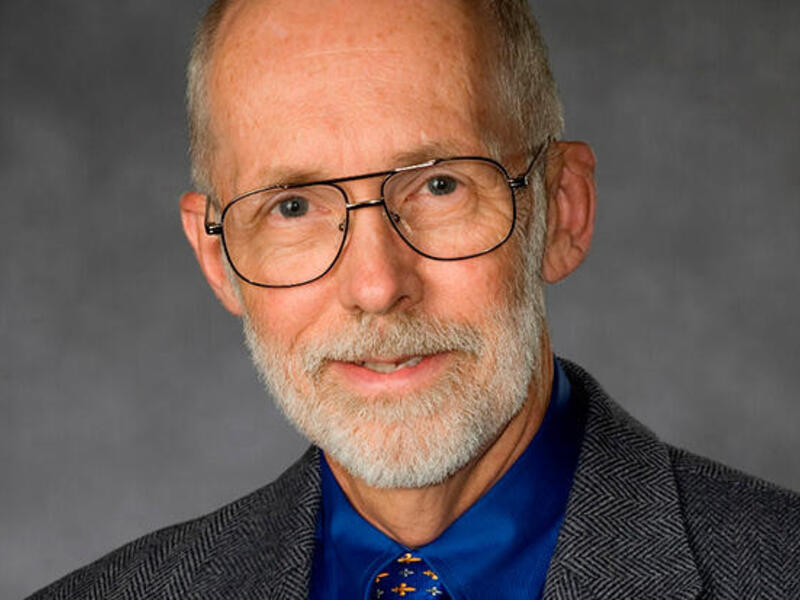

Global study on forgiveness was rooted in the work of VCU professor emeritus Everett Worthington

Share this story

People can learn to forgive. That’s the takeaway from Everett Worthington’s more than 35 years of scientific study on the subject of forgiveness.

“My mission is to do all I can to promote forgiveness in every willing heart, home and homeland,” said Worthington, Ph.D., a leader in the field of forgiveness and Commonwealth Professor Emeritus at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Worthington, a clinical psychologist, formally retired from VCU in fall 2017 after nearly four decades in the Department of Psychology. He recently played a pivotal role in a study and a campaign on forgiveness, both in collaboration with Harvard University and funded by a more than $1 million grant from the Templeton World Charity Foundation, which funds interdisciplinary research on what it means to be human.

The study, published in March in the international, peer-reviewed journal BMJ Public Health, included 4,598 participants, which is “more than all other intervention studies on forgiveness that have ever been done put together,” Worthington said.

The global study, conducted from 2019 to 2021, centered on REACH Forgiveness, originally a group psychoeducational program to promote forgiveness. It was created by Worthington in the late 1990s and has been found effective in over 30 randomized controlled trials.

The recent project used a do-it-yourself workbook, originally tested in 2014. Each of the six participating sites— Hong Kong, Indonesia, the Ukraine (two sites), Colombia and South Africa — received the same workbook and protocol.

“The point of this was to scale up an evidence-based intervention to help people forgive if they wished to do so,” Worthington said. “With this four-continent application, the literature is now more balanced, more global.”

On average, it took participants about 3.3 hours to complete the workbook. The outcome of forgiveness for a transgression was identical to a six-hour group session on the subject.

“We are getting more efficient at helping people forgive,” Worthington said. “The amount of forgiveness is at the same level, but it’s taking less and less time to do it.”

The study also found that completing the workbook resulted in less depression and anxiety.

“People were more flourishing in life with work and family. Hope was increased, and people slept better,” Worthington said. “Also, a person’s willingness not to get involved in arguments was better, as was their mental and physical well-being.”

Once the workbook was validated by the recent study, Worthington wanted to see if the concept could be used as a way to change society.

“That led to the second project, which focused on our Colombia effort,” he said.

The Colombia campaign, published online in the independent, peer-reviewed International Journal of Public Health, included about 3,000 participants at a private secular college.

“The idea is to give the university opportunities to be more forgiving,” Worthington said, adding that students learned about forgiveness through the workbook and a live, televised podcast with talks by five experts on forgiveness, including Worthington. “There were also other talks by local experts.”

Other opportunities to forgive included seeking to score almost perfect on a knowledge test, watching animated videos describing the REACH method, sitting under a forgiveness tree, praying or meditating about the person they wanted to forgive, and putting an adhesive note with the name of the person they wanted to forgive on a special wall.

The campaign produced large changes when averaged across the entire population of the university, increasing forgiveness and well-being and decreasing depression and anxiety.

“We wanted to find how to help whole communities create a more forgiving social environment for their members — so important in today’s climate of worldwide conflict,” Worthington said. “In Colombia, we found which types of activities made a big impact — the REACH workbook, the knowledge test and podcasts. We also found that busy people flocked to the brief ones, but those rarely did much lasting good. And we found which ones people avoided because they just took too long. Communities can now, we believe, create effective, efficient campaigns.”

The REACH Forgiveness workbook, which is free online in English, Spanish, Chinese, Indonesian and Ukrainian, can be used by organizations, businesses, schools, universities and communities worldwide.

As Worthington said, “it can promote more forgiving workplaces, schools, colleges, communities or individuals — in the USA or around the world.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.