June 17, 2024

Beyond the fab and the fun, the ballroom scene has deep meaning with deep roots

Share this story

For more than a century, ballroom – the scene, not the dance – has made a mark in American culture.

Today, if you throw “shade” at a rival or get the “tea” on last night’s party, you’re speaking the language of ballroom. If you grooved to Madonna’s “Vogue” in 1990, you were in ballroom’s pull. And a half-century before that, if you read Harlem Renaissance leader Langston Hughes’ autobiography, you got a glimpse of ballroom’s allure – the “strangest and gaudiest of all Harlem spectacles,” he wrote of the drag balls he attended.

Over the generations, the spectacle of the ballroom scene – a Black and Latino LGBTQIA+ subculture that developed out of the drag ball community – has grown, but its underlying heart has remained intact.

Virginia Commonwealth University’s Julian Kevon Kamilah Glover knows firsthand, from a young age, what drives ballroom culture. “It finally gave me an experience and a glimpse into what Black queer life could be and what my life could very well be in terms of both my gender and my sexuality,” she said.

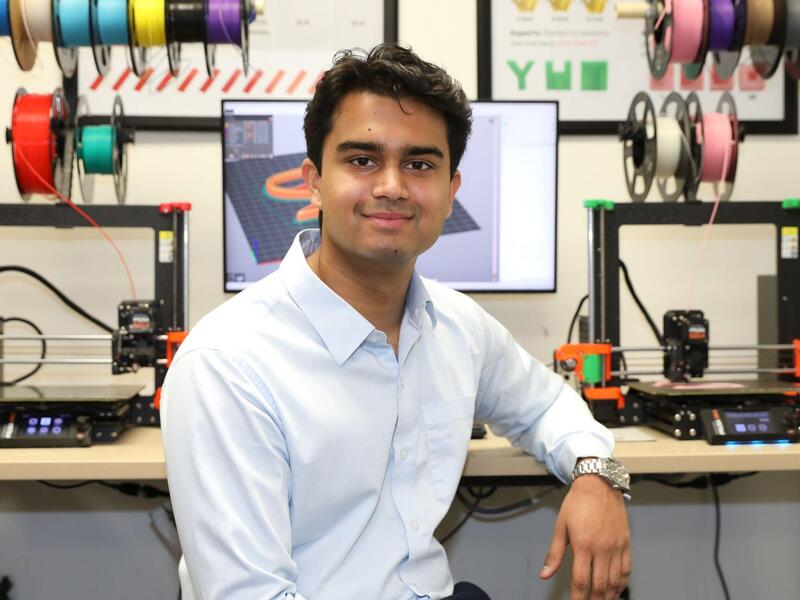

Glover, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the VCU School of the Arts and in the College of Humanities and Sciences, with positions in the departments of Dance and Choreography; Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies; and African American Studies. Her research focuses on Black and brown queer cultural formations, performance, ethnography, embodied knowledge and performance theory.

Glover spoke with VCU News about the ballroom scene – its deep roots, expanding footprint and lifesaving purpose.

You have a long and personal connection to ballroom culture – tell us about it.

I got introduced to the scene at the tender age of 16. I grew up Pentecostal in central Illinois, and my folks were vehemently against me being anything other than a cis, hetero person. Things culminated when my folks said, “Well, we’ve tried so many things to get you to turn away from your wicked ways, but you haven’t. So you’re going to have to leave the house.” So – I think much to their surprise – I did.

I got a one-way ticket on Amtrak to Chicago, which was the nearest major city. I didn’t have much money and didn’t have anywhere to go, but it felt better for me to be there where I could be myself, rather than live at home under my parents’ auspices. During that first day, I ran into three femme queens, or trans women, who took me under their wing; gave me food, shelter and clothing; and, most importantly, introduced me to the ballroom scene.

It reminds me very much of the TV show “Pose.” At the very beginning, one of the main characters gets kicked out of their family home and gets on a bus to New York City because he wants to dance. So he’s dancing and one of the femme queens walks by, sees him and invites him to be part of her house, and the rest is history.

It really resonated with my own experience. That’s just a glimpse of the kind of lifesaving effect that the ballroom scene continues to have for so many people. While my relationship to the scene is in a state of continuous transition, I can never forget the foundational lessons about love, about care, about intention and about affirmation that the scene taught me.

“Pose” reflects how ballroom has permeated broader culture, including our vocabulary, but it’s a complicated mix, right?

Even though ballroom has become more of a practice around the world, it still maintains its insularity, especially in the United States. This is because this was a space that was created by and for Black and brown LGBT people who did not feel welcome in white, queer or gay spaces because of their race – and also did not feel welcome in Black and brown spaces because of their gender and sexuality.

This is a constant tension within ballroom and beyond, because many of the words that we use in common parlance today emerged from ballroom scene, but they’re now misattributed.

One example is “reading” [the art of insults]. While people might in a cursory way know that because of the cultural power of television shows like “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” it tends to get misattributed, and the original meaning tends to get lost as it gets pushed out more into the public. Also terms like “tea” [news or gossip] and “shade” [a jab or insult] – all of these originate in ballroom and over time have had their original context muddled, much to the chagrin of folks in ballroom who remain rather insular.

So I think it’s really important to recognize and acknowledge where these terms have come from.

Speaking of roots: What’s the brief history of the ballroom scene?

The earliest iteration started in the Harlem Renaissance, and the scene has developed quite a bit. It used to be a space where people really came together and the uniting factor was their sexuality and gender. In the mid-1960s, intercommunal racial tensions flared, causing the Black and brown folk to develop their own scene. It was loosely inspired by the drag balls, but they took it in a very different direction.

There are several epochs, or eras, in ballroom. In the 1960s and early ’70s, there was quite a big emphasis on being a showgirl, if you will – a kind of Old Hollywood glamorous star. Then came television stars [from] shows like “Dynasty.” You see that in the legendary documentary “Paris is Burning,” which highlights the ballroom scene of the late 1980s and early ’90s and a changing of the guard from Old Hollywood to television stars to movie stars to celebrities.

The advent of the digital sphere has made the foundational contributions of ballroom more readily accessible. So from the 1990s through today, we begin to see ballroom chapters [or] house chapters start to pop up literally all over the globe – in places like Paris or London or Japan, or even some parts of Russia.

The 1990s might have been my favorite era, in large part due to the contributions of some of the scene’s progenitors. By that I mean Black and Latinx femme queens who are at the forefront of developing the dance that we now understand to be vogue. It really cemented the influence and the contributions that trans women have made to ballroom that extend into today.

Vogue – the dance and the Madonna song – seems to touch on that line between ballroom’s popularity and deeper significance.

It just speaks to what happens when a cultural formation that is made by Black and brown queer folks gets exported. Even after “Paris is Burning,” what happened? Madonna, who created the song “Vogue,” introduced the ballroom scene to a much wider audience that was more interested, I think, in its spectacularity than what it actually provides its members.

It’s not just about the competition – it’s about the kinship formations. It’s about the ritual performance. It’s very much a way of understanding and receiving acceptance and affirmation for many people whose gender and sexuality meant that they were excluded from their families or disowned by their families.

So ballroom is not just about spectacle for spectacle’s sake. It’s not all about having fun and being fab. Ballroom has saved and continues to save so many lives.

You mention ritual performance – it’s a really meaningful part of ballroom.

The scene focuses so much on the experiences of brown and Black LGBT people, who are continually told by society that we have little to offer on the one hand yet are vectors of disease on the other hand. My introduction into Black LGBT life was through the context of AIDS. It was the fear of God that people tried to put in me, to say, “Don’t join these communities because you’re going to inevitably end up dead.” So often, the experiences of Black and brown LGBT folk emerge through, or in proximity to, our deaths.

Ritual performance offers a way to honor the contributions of people who society says contribute nothing or have nothing to contribute. It allows the community to honor its icons while they yet live. That’s one of the reasons why it is really important.

I’ll give you one quick example: LSS – legends, statements and stars – is the time at the beginning of every ball that honors people in the room who have made significant contributions to ballroom. They’ll have the runway essentially in the middle of the room, and the emcee will individually call up every person they see who has been deemed a legend, a statement and a star to give them their moment and give them their opportunity to shine, give them their flowers while people can smell the flowers.

That is such an important thing, because we live in a world where the stories and contributions of Black and Latinx trans people really only become important after folks have died.

Share a final thought about ballroom’s role in the larger LGBTQIA+ culture.

At the root, it gives this message that transformation is worth doing and transformation is possible. You do not have to simply accept the gender or the sexuality that heteronormative society wants you to have. You have a hand in the creation of yourself. And there are people out there who are just as committed to a kind of self-definition, and you can get together, have fun, learn some things about yourself and learn some skills that can be used in the real world.

Each issue of the VCU News newsletter includes a roundup of top headlines from the university’s central news source and a listing of highlighted upcoming events. The newsletter is distributed on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. To subscribe, visit newsletter.vcu.edu/. All VCU and VCU Health email account holders are automatically subscribed to the newsletter.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.