Aug. 6, 2024

VCU professor Rebecca Gibson’s new book looks at the philosophy of the Matrix franchise

Share this story

What does it mean to be human? That’s the riddle that anthropology ultimately seeks to solve. Rebecca Gibson, a teaching assistant professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, said that while there is no definitive answer, the pursuit leads to fascinating corners – including a science fiction film from 1999.

“There’s a reason that philosophical debates span thousands of years,” said Gibson, Ph.D., who teaches anthropology in the School of World Studies. “But ‘The Matrix’ franchise has an extremely solid take on the matter: The answer is in the questioning.”

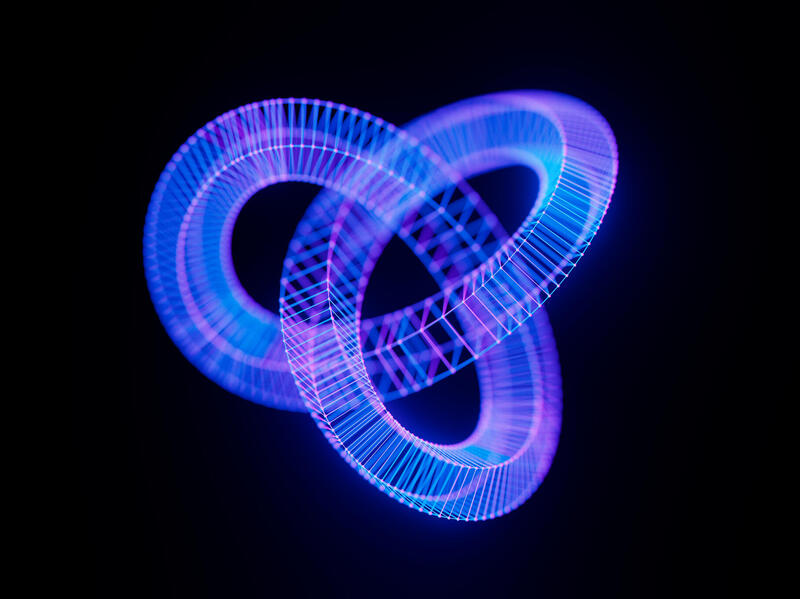

In her new book, “Cyborgs, Ethics, and The Matrix: Simulations of Sex and Gender,” Gibson explores the film franchise, its relationship with sex and gender, and its emphasis on the interconnectedness of people, as well as current and potential cyborg (human-machine hybrids) technology. The book, released in July, is Gibson’s fifth overall and her first to be published while a full-time faculty member at VCU.

Gibson spoke with VCU News about the origins of her fascination with “The Matrix” and what the franchise can tell us about ourselves.

What sparked your interest in “The Matrix” and its relationship with sex and gender?

I first saw “The Matrix” when it came out in theaters in 1999. I was 18, financially stuck in a small town in Indiana, about to graduate high school and soon about to be a college dropout – though I didn’t know it yet. I thought the movie was the coolest thing I had ever seen, and I wanted to be that cool someday.

I watched the second and third “Matrix” movies but didn’t think much of them, and the franchise faded into just something within my pop-culture repertoire – something to talk about at parties, but not much else.

When I returned to Indiana University South Bend to finish my undergraduate degree in 2008, gender became a focal point for my research. My main question when reading (and now writing) a syllabus has always been, “Where are the women?!” Though this has expanded to be intersectional – by also asking where are the Indigenous voices, the people of color, the disabled voices, the voices of the impoverished – examining why approximately 50% of humanity often gets left out of so many things, sci-fi pop culture included, continues to be one of my passions.

“The Matrix” franchise is a product of two transgender women – Lana and Lily Wachowski – and while their gender is far from the most important part of their contributions to the world of filmmaking, it is significant in terms of shifting narratives surrounding who creates, what they create and why.

What can “The Matrix” tell us, anthropologically speaking?

With its central philosophical premise being “know thyself,” the franchise’s machine/man struggle is another nature/nurture type of conflict. And true knowledge comes in the form of realizing that it is not either – it is both.

We are born with instincts, urges and certain physical and psychological limitations. We are shaped within those constraints via the inputs of our societal norms – what anthropology calls habitus. But we also have free will and agency, or the ability to choose to do other than what we were taught, how we were shaped. To know ourselves, to understand what it means to be human, we need to ask the question in the first place.

This is much the same question asked and unanswered by Lewis Carroll’s books “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” and “Through the Looking-Glass,” both of which feature heavily in the various “Matrix” franchise properties. The Caterpillar asks Alice, “Who are you?” And while Alice really never knows exactly, by the end of her adventures she knows she is a different person than the one who went down the rabbit hole.

Anthropology looks for similarities, for so-called “universals” that connect the various cultures of the world. And while there aren’t many that are agreed upon, that urge for self-discovery – the question of who, what and how we are human – is one that spans the world and the ages.

How does this relate to your other research?

As a biological anthropologist, I relish the fact that I can use anthropology to study anything that interests me. We are in an age tentatively called the Anthropocene, the age where humans and our actions have touched almost every part of the world. Biological anthropology studies the biological and biocultural aspects of humans and humanity, but it doesn’t end where the body does.

My primary research focus is the human skeleton, specifically how certain types of behavior – in my case, the clothing that we wear – changes skeletal morphology. This can be seen in my second book, “The Corseted Skeleton: A Bioarchaeology of Binding,” and a book I am currently working on with VCU alum Tell Carlson, tentatively titled “Well Heeled: A Bioarchaeology of the Shoe.”

But the skeleton is only one part of our biology. I also research robots and zombies and vampires and poverty and disability – all things that are rooted in the biology of humans. Despite their disparate conceptualizations, these all have implications for our future.

Take, for example, zombies. The novel “World War Z” by Max Brooks can be seen as a contagion allegory: What would a global population, divided by borders and cultural differences, do in the event of a mass disabling and lethal plague? Brooks wrote that book in 2006, and in March 2020, we got the answer as the world shut down for the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Regrettably, it seems Brooks was prophetic in several ways, which analysts of his fiction, including myself, have repeatedly pointed out.

So the body itself represents as much a question as an answer, right?

“The Matrix” asks us who we are, and it roots that question directly in the physicality of the human body. The machines are set up as the enemy, but those who can most effectively fight the machines from inside the system are those who are part-machine themselves – humans who have taken the Red Pill and woken up from the Matrix simulation.

While the Wachowskis have affirmed that this is a metaphor for being transgender, it is also a larger discussion of what the human body even is: Are we locked into the confines we are born with, or can we step outside of that and make the choice to be more, different, than we were?

If we are going to change anything about our future – from climate change, to how we respond to the next pandemic, to the way disabled people exist in the world – we will need research like mine that makes connections between pop-culture ideas, which easily and quickly spread through the zeitgeist, and real-world issues that need physical and technological solutions.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.