Sept. 30, 2024

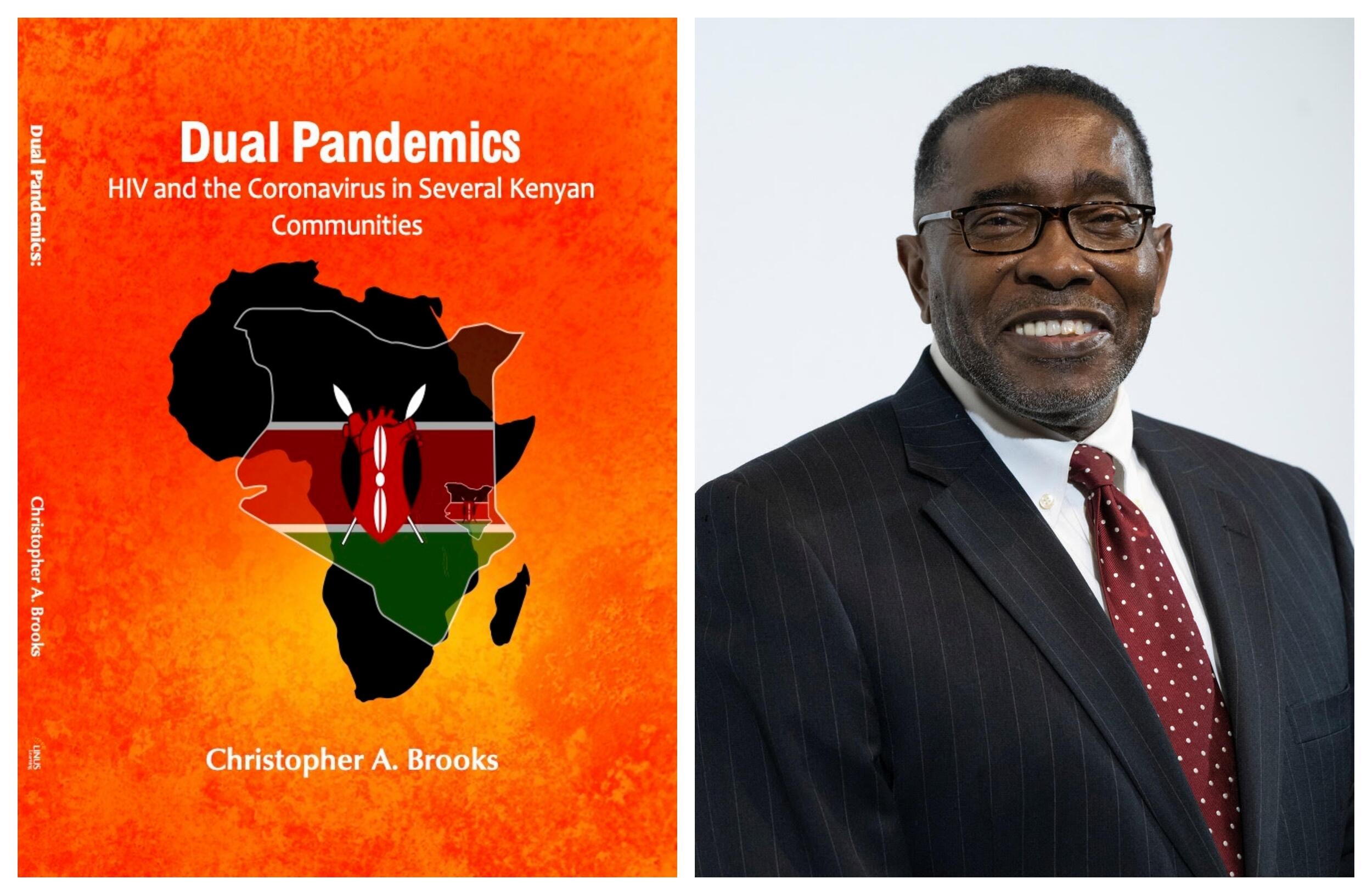

Author Christopher Brooks looks at two pandemics – HIV and COVID – in latest book

Share this story

For more than a decade, author Christopher A. Brooks has spotlighted the impact of HIV on communities around the world. Since 2009’s “Dangerous Intimacy: Ten African American Men with HIV” – a collection of unscripted biographical accounts from the men – Brooks has traveled to South Africa, Mali and Kenya for his research.

In his latest book published by Linus Learning, “Dual Pandemics: HIV and the Coronavirus in Several Kenyan Communities,” Brooks, Ph.D., a professor of anthropology in the School of World Studies in Virginia Commonwealth University’s College of Humanities and Sciences, explores the concurrent effects of HIV and coronavirus on people in the East African country.

“As I was interviewing people about their HIV management, it occurred to me to ask about how they negotiated the coronavirus, and I got varied responses,” Brooks said. “There was a good deal of folkways and misunderstanding surrounding it.”

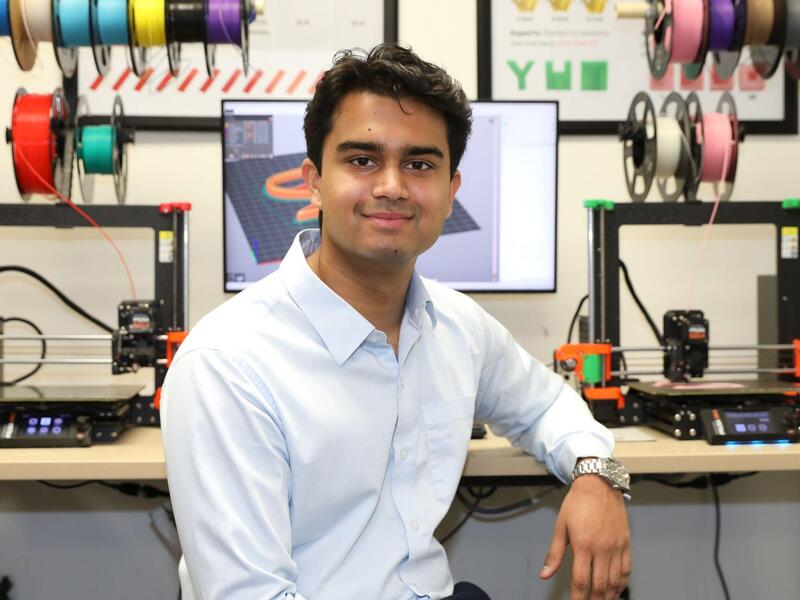

During the research process, Brooks relied on help from several of his undergraduate students, including high-schooler Sidhartha Basu, who took an introductory anthropology class with Brooks as part of the VCU Advanced Scholars Program and then worked as his research assistant.

“The research I did with Professor Brooks was my first foray into academic research in anthropology,” Basu said. “This was so different from what I thought research meant – collecting data from field notes and then analyzing it to draw conclusions, instead of labs and powerful computers crunching data.” Another of Brooks’ students, Delaney Ludwig, designed the book cover.

VCU News spoke with Brooks about his latest work.

Why did you decide to do a series on the HIV pandemic?

Linus Publications approached me back in 2008, and they knew that I had a professional and scholarly interest in the contraction and spread of the virus. I was working with a facility, the Minority Health Consortium in downtown Richmond, doing HIV testing and counseling. Then, Christopher Lance Coleman, a former colleague at the VCU Nursing School, asked me if I would be willing to collaborate on a book dealing with African American men and the virus. That’s how it began. I was telling their stories.

I focused on men initially because for every man who gets the virus worldwide, there were 12 to 13 women who contracted the virus – mostly from their male partners. Justifiably, most of the research attention has been given to women and children. I felt obliged to tell the story of the men who were dealing with, handling and living with the virus.

I did the same thing in South Africa. In Mali, I had the opportunity to tell the story of women facing the virus. That was very revealing in that Mali is 90% Muslim, which added a whole new layer to researching that HIV experience. I found in South Africa and other places (especially Mali) that there was a good deal of judgment – and it often resulted in blame being placed on women, although they were typically infected by their men. In addition, most women are still unable to persuade their male partners to use condoms.

Your latest book deals with the effects of two pandemics at the same time. What did you find during your research?

I was supposed to begin this work in fall 2020. In October, I was scheduled to go to Kenya, but of course, COVID-19 came along and shut everything down, including Kenya. I wasn’t able to resume work on this project until spring of 2022.

When I was able to travel to the country, it was under very strict conditions. Kenya had a rigorous protocol in place. The government shut down the schools; you couldn’t have your children on the street unless they were seeking health care. Hospitals restricted visitors and limited such visits to loved ones. So, as I was interviewing people about their HIV experience, it was logical for me to inquire about how they navigated these dual pandemics.

I asked my informants what their contact was with COVID-19, how knowledgeable they were about it, had they come in contact or did they know someone with it. And finally, I asked if they knew how to avoid it.

One of the biggest takeaways was that we still have a good deal of work to do in order to combat some of the prejudices surrounding these health emergencies. For example, we know there are some high-risk populations where HIV is concerned, including injection drug users and men who have sex with men. Those aren’t easy groups to identify in Kenya because same-sex relationships are still technically illegal.

If I had captured those voices, I would have been able to present a more holistic and inclusive picture of the virus in the country. But if an informant had come forward and identified themselves as such, it might have been risky, even though I used pseudonyms for everyone whose narrative is in this book. What is unique about “Dual Pandemics” is that unlike my previous works on the topic, I surveyed men and women in roughly equal numbers.

I must say how grateful I am to my editor at Linus, Jay Herath. He shepherded this series over so many years. I look forward to our continued collaboration. And, of course, I am grateful to all of my students. Each of them is acknowledged in the book.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.