Feb. 3, 2025

From nurse to narrator with alum Michael Sullivan and his play ‘WillJee’

Share this story

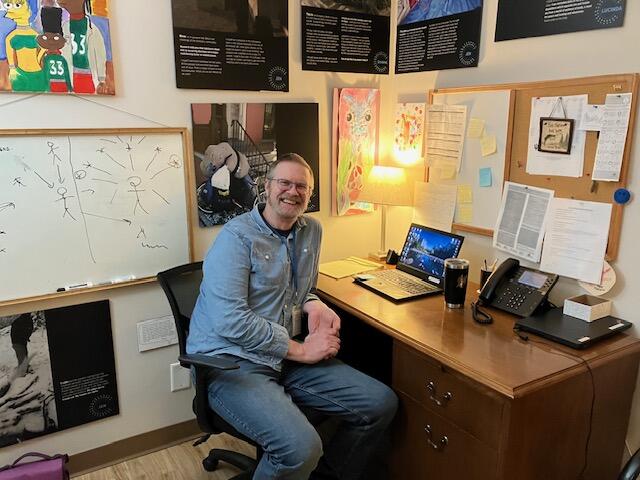

When audiences step into The Lynn Theatre to experience the new play “WillJee,” they will embark on a journey that blends humor, heartbreak and the miraculous. Written by Michael Sullivan, a graduate of the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing’s psych mental health nurse practitioner program, the play draws on his unique perspective on care, sacrifice and the human spirit.

The comedy centers on Will, a man grappling with his younger sister’s impending death. With unexpected help from the statue of St. Francis—and possibly from something he consumes—Will discovers a surprising ability to heal. But the power comes at a cost, raising questions about connection, resilience, and what it truly means to help others. The play is being held at the Lynn Theatre at Brightpoint Community College’s Midlothian Campus with performances through Feb. 6.

For Sullivan, the play is deeply personal. His nursing background not only informs the emotional depth of his storytelling but also inspires his exploration of themes like healing and sacrifice. Ahead of the play’s debut, he discussed the inspiration behind “WillJee,” the challenges of balancing comedy and emotional depth, and how his experience as a nurse shapes his creative vision.

What inspired you to explore both nursing and playwriting?

I’ve always been a bit of a career hopper. Up until I became a nurse, I’d switch industries about every two years. I worked in construction, banking, house painting, news reporting, sales, music teaching, storytelling, photography, among others. When my wife and I had children, our second one was a bit rambunctious and was getting stitches every other week jumping off something. I decided I should get a nursing degree so maybe we could cut down a little on all the ER visits. Seriously, that was the thought.

When I graduated, the timing was a bit off. It was a new program at Brightpoint Community College (formerly John Tyler Community College) and we finished late May, early June, so all the new nurse positions were filled. The only one available was at the Virginia Treatment Center for Children, doing pediatric psych. The first week there I’m on a unit trying to help a struggling kid by telling them stories, singing a little song. It worked! Felt like the perfect place for me. The next week I was helping to paint some walls there, which kind of sealed the deal.

Playwriting came late to me — after I turned 50. I’ve been writing since I was a kid and have made a living as a freelance writer and a reporter at times. After our first child (yes, they do seem to change you, don’t they?), I wanted to be able to read them stories or poems that I’d written, so I focused on children’s writing for about 10 years. This led to a few poetry anthologies and several poems and stories in Highlights Magazine. They awarded me a Pewter Plate for Outstanding Contributions to Children’s Literature one year.

About two-and-a-half years ago, my younger sister Mary was placed in hospice and I drove up to help care for her with my older sister, Jen. Since we’re that kind of family, I told her I intended to write a stand-up routine about her passing and that I would bring her ashes up onstage as a prop. She thought that was a great idea and made me promise to do it. I started writing it the first week I was there. I would do a little at night, then bring it up and read it to her the next day, then do a bit more.

She was given four to six weeks, so obviously there was a bit of a rush. Although she stayed with us for almost four months, the writing task ended up being too much for me to do. The stand-up routine ballooned into this very long, very complicated, very convoluted life tale. It was disheartening in a lot of ways. As the universe would have it, later that year an opportunity arose to participate in Cadence Theater’s Pipeline New Works Fellowship, mentored by Tony-winner David Lindsay-Abaire. I applied and got in.

In what ways have your experiences as a nurse influenced your motivation to create characters and tell stories?

I’ve been lucky (unlucky?) enough to have been on both sides of the bed, so understand very well the power of stories and experience. At one of the lowest points in my life, around the age of 21, it was a patient tech that helped me stay grounded on this planet simply by walking the halls of the unit with me. When he didn’t, my mind traveled too fast and in too many directions for me to last. When he spoke to me and we chatted, I slowed to a pace I could think at. It was that black and white.

Later, when I was on the other side and talking to people experiencing similar things, I was able to bring the knowledge and experience of that moment and many others like it into my practice. Being a nurse means listening to a lot of very painful stories, stories often never told before by that person. The fact that they are speaking it means that they somehow survived, though. So among all the mess there has to be a smidgen of hope. I like stories that find that smidgen when it mostly feels like it shouldn’t exist. I think it’s important to be able to call on those when we need them. If someone else got through it, I can.

The play's main protagonist, Will, experiences a journey that touches on the emotional and ethical complexities of caregiving. Did your nursing experience shape how you portrayed his struggles and decisions?

In the play, his mother is a former psych nurse who spent decades in the trenches, so to speak. I’m sure I’m like many other people who choose psychiatry as their profession in that we often find today’s actions are traceable, but only if we ask.

As an example, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve spoken to people with insomnia who complain of this anxiety that starts at a certain time every day and then keeps them up all night. With a little questioning, you discover that 5 p.m. or 7 p.m. was the hour when someone came home and the chaos in the house started. What kid would sleep well through that? What kid would ever sleep well later if that went on for years? It’s rare to find someone with a simple story. It’s common for us to judge what we see in front of us. Kind of all goes back to that Swiss cheese model they put on the board in school. How many things have to go wrong to fall all the way through?

Tell us about your experience working alongside David Lindsay-Abaire, a Tony- and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, screenwriter, lyricist, and librettist.

Gosh, I’ll gush! It was amazing. I had never studied writing formally before. I will say mostly “hands on.” My first writing gig was compiling obituaries for a newspaper. There is definitely a structure to those. There has to be. Finding a structure for longer things on the fly is challenging, and leads to a monstrous amount of copy and no discernible narrative. He started with giving us the basics of story structure and then gently prodded us back to this over and over. Often I’d have the information in the play but had just left it sitting there, unattended, or piled so much on top of it, that I’d lost it. He’d say something like, “You know you made the mother a nurse,” and I’d be like, “Duh!, use that, Michael!” And the scene would get back on its legs again and continue.

David is a kind and generous and deserving of all the accolades. A wonderful man.

And also, all the flexing possible for Cadence [Theater Program] in running this program. Wouldn’t have happened without them.

How do you see your playwriting and nursing influencing each other as you move forward in your career?

My hope is to continue to explore mental health stigmas through my writing and become a better storyteller. Given the weight of the stories we can hear in psychiatry, I think it’s healthy to have this outlet. I love the idea of the compassionate witness.

As my knowledge base expands and the field itself expands, it seems like there’ll be plenty of opportunities to continue to define and refine our understanding. We learn best as humans through stories, so they’ll continue to be needed.

A longer version of this story was originally published on the VCU School of Nursing’s website.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.