Feb. 13, 2025

School salad bars raise fruit intake among kids and benefit economically diverse schools, VCU researchers find

Share this story

School salad bars boost how much fruit kids eat but don’t drive up vegetable intake, according to a new study by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU. That’s still good news for salad bars, which some schools have installed to help kids meet the fruit and vegetable guidelines of the National School Lunch Program and the Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010.

Melanie Bean, Ph.D., and VCU colleagues tested whether salad bars increased elementary school students’ fruit and vegetable intake in one Virginia school district. The study, published Feb. 5 in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, demonstrates the positive impact of school salad bars on kids’ nutrition. It builds on previous findings from the same research team, which found that school salad bars improved the overall dietary quality of students’ lunches.

“What’s really important is that vegetable intake did not go down,” said Bean, a professor in the School of Medicine’s Department of Pediatrics and co-director of the Healthy Lifestyles Center at CHoR. “Students were still eating the same amount of vegetables with the salad bar. They were just adding fruit, and eating more fruit. Students in salad bar schools also selected a greater variety of fruits and vegetables, potentially leading to a greater range of nutrient intake.”

The school district installed salad bars, which featured a rotating variety of four vegetables and three fruits, into all of their elementary schools over several years. The research team randomly selected seven schools receiving salad bars and paired them with control schools with similar demographics. The researchers matched the school pairs based on their Title I status, a designation where at least 40 percent of students live below the poverty line. Among the Title I schools, between 60% and 100% of students received free, federally funded lunches.

“We know that fruit and vegetable intake in particular is lower among families who are under-resourced, and that their risk for chronic disease is higher,” Bean said. “School meals play a particularly important role for these families.”

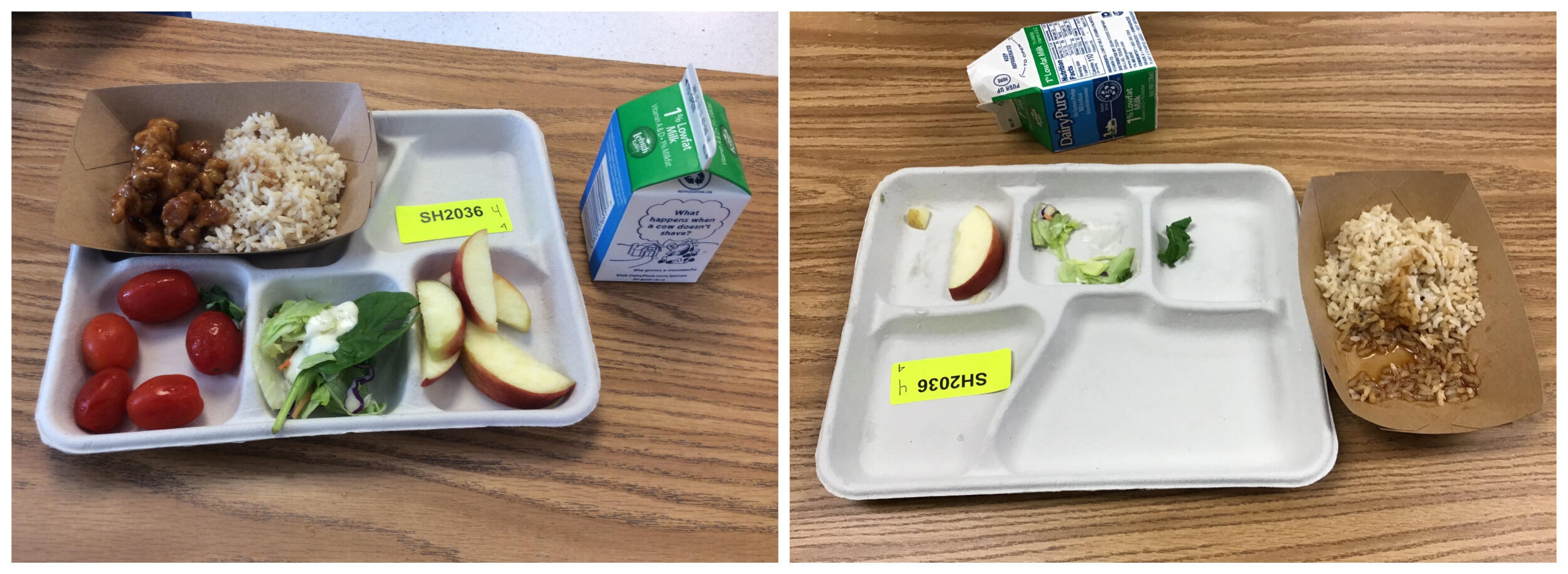

Researchers measured the amount of fruit and vegetables kids ate by taking photos of their lunch trays — over 13,000 photos from 6,623 students — before and after lunch. They then estimated how much the students ate, as well as how much food waste the kids left on their plates, before salad bars were installed and four to six weeks after installation.

The research team found that students in “salad bar” schools ate approximately one-third of a cup more fruit than they did before the salad bars were installed, and around one-third of a cup more than students in control schools, who were served fruit and vegetables in a typical lunch line throughout the study. Vegetable consumption — approximately one-quarter of a cup — stayed the same in both groups.

That could be because most kids naturally prefer fruit over vegetables.

“Sweet tastes are more palatable, and we hypothesize that kids were more familiar with some of the fruits versus the vegetables,” said Suzanne Mazzeo, Ph.D., a professor in VCU’s Department of Psychology in the Colleges of Humanities and Sciences and one of the study’s co-authors. Over time, Mazzeo said, students might choose more vegetables from the salad bars.

The researchers also found that fruit food waste increased very slightly over time in “salad bar” schools but not in control schools, while vegetable food waste was unchanged in both.

Strikingly, the results were consistent across Title 1 designation, which means that all kids benefited from the salad bars.

“The National School Lunch Program, and salad bars within the National School Lunch Program, are in some ways kind of an equalizer,” Bean said. “It overcomes those disparities that we see in fruit and veggie intake across sociodemographic groups.”

The study’s co-authors include Lilian de Jonge, Ph.D., a professor at George Mason University; Laura Thornton, Ph.D., a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Hollie Raynor, R.D., Ph.D., a professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville; Ashley Mendoza, a research coordinator in the Department of Pediatrics and at ChoR; Sarah Farthing, a research manager in the Department of Pediatrics and at ChoR; and Bonnie Moore, from the nonprofit Real Food for Kids.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.