Feb. 12, 2025

The legacy of the singular American writer Tom Robbins lives on at VCU

Share this story

Tom Robbins may have said it best – with a wink and a final set of parentheses – when he inscribed a copy of a book based on recollections of his colorful life as a writer.

To VCU (nee RPI), who made me the man I am today. With thanks (and apologies), Tom Robbins - Feb. 2011

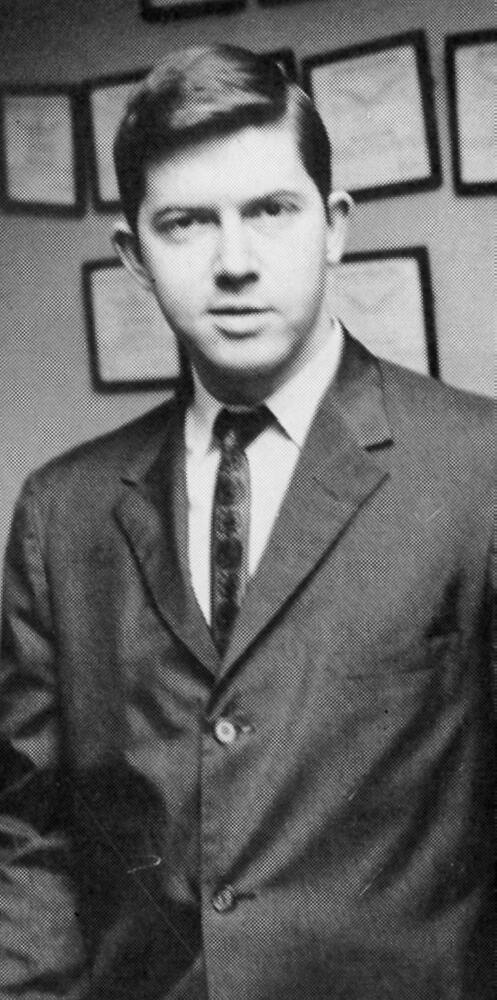

No apologies needed. Robbins, who was once described by People magazine as “the perennial flower child and wild blooming Peter Pan of American letters,” died Feb. 9 at age 92. In works such as 1976’s “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues,” which was notably adapted into a 1993 film he narrated, the Richmond Professional Institute alum showcased a unique literary voice – a writer who, as People described, “dips history’s pigtails in weird ink and splatters his graffiti over the face of modern fiction.”

A native of western North Carolina, Robbins graduated with a journalism degree from RPI, Virginia Commonwealth University’s predecessor institution, in 1959, and he never lost sight of the school’s influence on his trajectory. In his 2014 book, “Tibetan Peach Pie: A True Account of an Imaginative Life” – which he insisted “is not an autobiography. God forbid!” – Robbins claimed five hometowns, Richmond among them. And VCU Libraries remains home to a legacy that future generations can continue to explore.

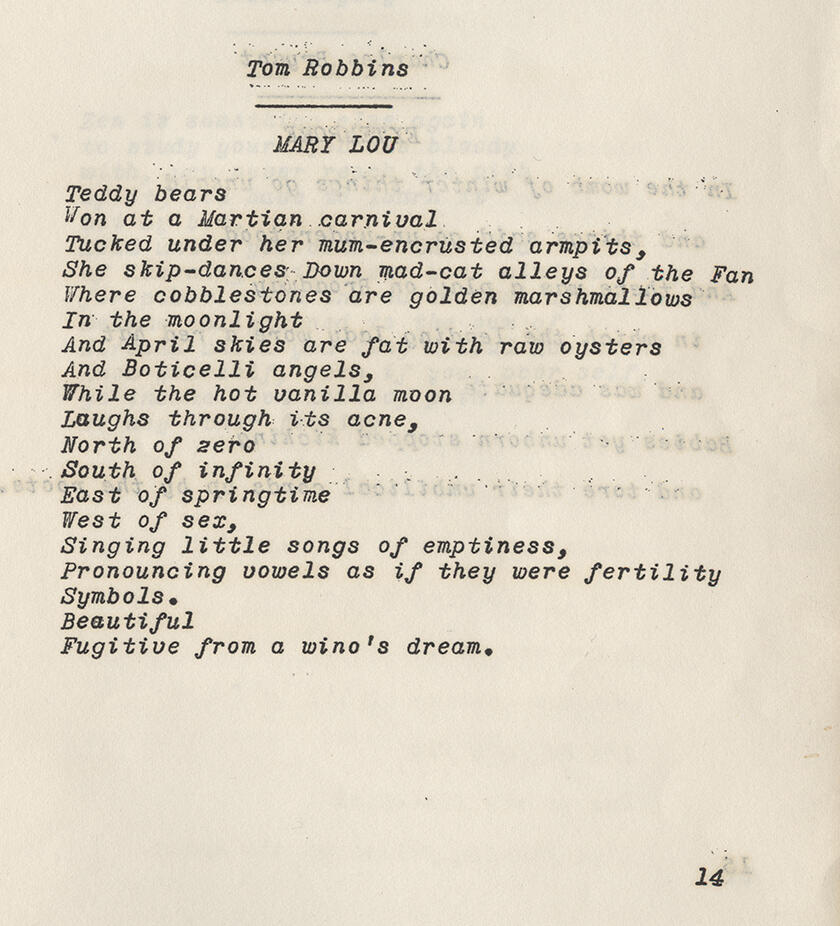

Beyond Robbins’ novels in its general collection, VCU Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives houses his papers, including manuscripts for his novels and some of his other works. It includes handwritten drafts, typed versions of drafts and galley proofs.

The collection also includes fan letters and spiral notebooks with personal flourishes. In a handwritten postscript to a broadcasting contract, Robbins wrote: “I should warn you that you may have to press your bleep button a few times.” A business card describes him as "Part-time Buddha, Menace to Society, Admirer of Clouds.” (An online gallery, “Tom Robbins: An Imaginative Life,” captures his spirit.)

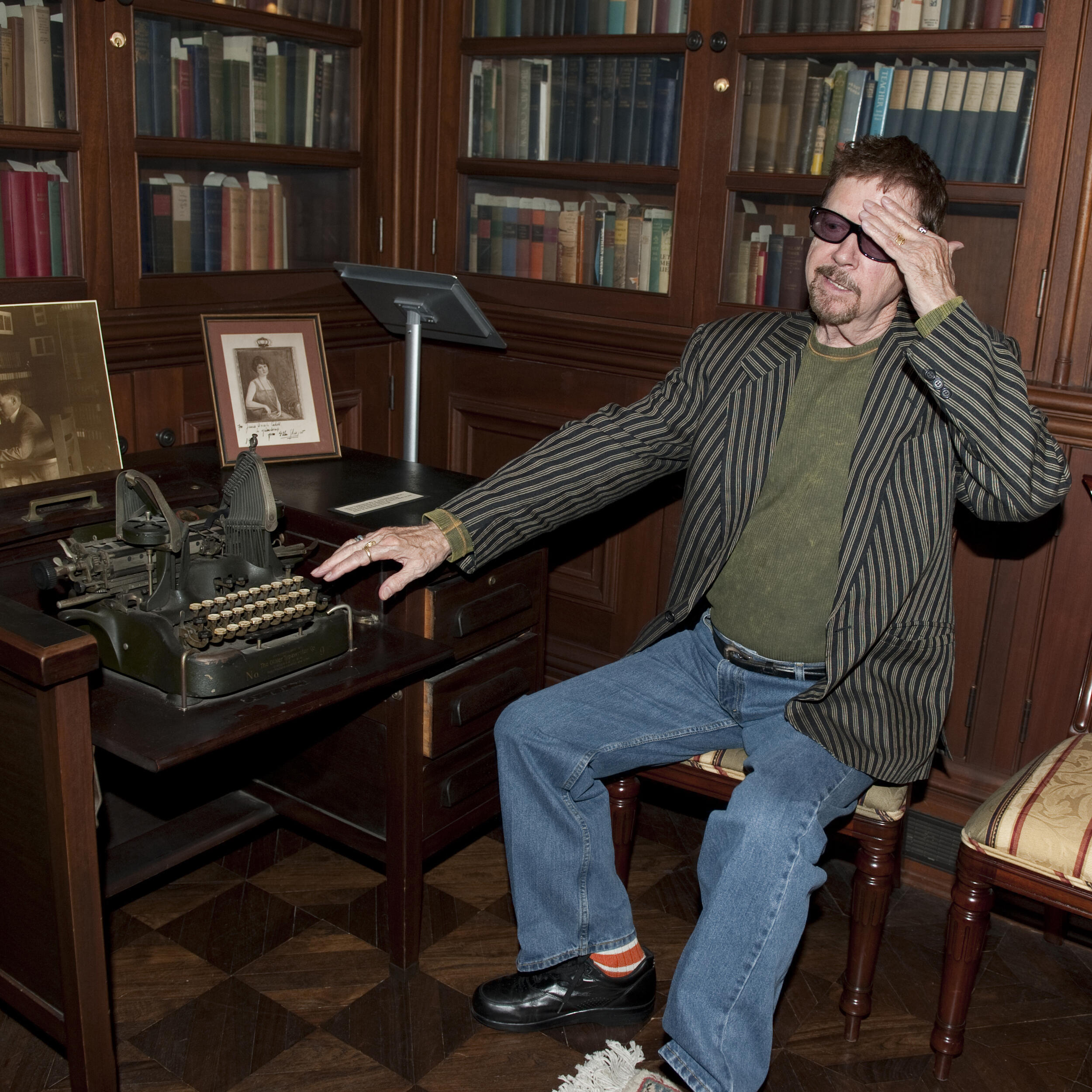

John Ulmschneider, who retired in 2020 as VCU’s dean of libraries and university librarian, worked closely with Robbins in acquiring the author’s papers, and he gleaned special insight from their sessions in Washington state (where Robbins lived for decades), North Carolina and Richmond.

“Critics never fail to point out the creativity of his plots, the beauty of his language and the power of philosophical discourses that appear in his work,” Ulmschneider said. “But I don’t see them recognize a crucially important element: the affection and sentimentality that suffuses his work and his characters. He creates his literary worlds with love and spirituality, and it shows in the affectionate portrayals of many of his characters.

“I hope his work gains recognition for that characteristic affection,” Ulmschneider continued, “because it reflects so much of Tom’s own affection for the world and for everyone around him.”

In his Richmond days, Robbins lived in the Fan District and became part of the local bohemian art scene. He was a regular at a number of bars on West Grace Street, including the Village Café, which remains a fixture of the VCU landscape. Robbins edited the RPI newspaper Proscript in 1958-59, and he wrote columns (“Robbins Nest” and “Walks on the Wild Side”) that contained early elements of his irreverent writing style.

Richmond writer and VCU alum Dale Brumfield, in a 2015 piece in VCU’s The Commonwealth Times, revisited Robbins’ final column from his RPI student days. In May 1959, as Brumfield wrote:

Robbins said goodbye to many of the colorful locations, teachers and eccentrics he profiled over the course of the school year before renouncing his original post-graduation plan to float to Hawaii in a martini shaker.

“I vow to keep right on in my frantic effort to purge American civilization of its complacency, to continue to stir up the animals and to trod on the toes of abominable bridge players and dullards who take automobiles and athletics seriously. Nothing bores me as much as sanity.”

After graduation, Robbins worked briefly as a copy editor at the Richmond Times-Dispatch – in a Facebook post this week, a former RTD acquaintance recalled how Robbins was remembered for selecting photos of Black celebrities for a syndicated newspaper gossip column, in an era when such judgment was often challenged. Robbins then moved west to Seattle and environs.

He wrote arts criticism for The Seattle Times and hosted the alternative radio show “Notes from the Underground.” Robbins said that it was in 1967, while writing a review of a Doors concert, that he found his literary voice. His skills were featured in articles and essays for Esquire, Playboy, The New York Times and GQ. And from his West Coast base, Robbins lived large and wrote counterculture novels that became cult classics.

“Even Cowgirls Get the Blues,” which filmmaker Gus Van Sant brought to the big screen with stars Uma Thurman, Keanu Reeves and many more, was among numerous works by Robbins that “charmed and addled millions of readers with screwball adventures,” The Associated Press wrote upon the death of “the novelist and prankster-philosopher.”

Other titles include his 1971 debut novel, “Another Roadside Attraction,” along with later works “Still Life with Woodpecker” (a love story whose topics include aliens and a pack of Camel cigarettes), “Jitterbug Perfume,” “Skinny Legs and All” (its characters include a dirty sock and a conch shell), “Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas,” “Fierce Invalids Home from Hot Climates,” “Villa Incognito,” “B is for Beer,” “Wild Ducks Flying Backward” (short writings) – and “Conversations with Tom Robbins,” a book about him in which the VCU Libraries copy includes his proudly inscribed VCU roots … and his parenthetical “apologies.”

Tom De Haven, the retired VCU English professor and novelist, recalled the joy of meeting Robbins when the author was donating his papers to VCU.

“It was a genuine thrill. When I was an undergraduate at Rutgers-Newark, I read ‘Another Roadside Attraction.’ … I couldn’t believe that you could write and get published and become famous for writing fiction like that! Game-changer for me,” De Haven said of a writer who had “the kind of imagination that comes up with astonishing stuff every page or two.”

De Haven added that Robbins kindly wrote the foreword to “Richmond Noir,” a 2010 collection of short stories from local writers that explores the dark recesses of the River City.

“For what everyone else got, like 50 bucks, his only demand: We couldn’t change so much as a comma,” De Haven said. “And we didn’t."

The vibrancy of Robbins’ writing and story lines was evident off the page, too. Ulmschneider reflected on the house in La Conner, Washington, that Robbins lived in – and developed into a character in its own right.

“It started out as a single tiny house – all he could afford when he first moved there in 1970,” Ulmschneider said. “He steadily added to it by building extensions around an open yard area, in which he planted a little tree just when he moved in. Eventually, over many years, the single house became a rambling home/exhibition hall/office completely surrounding a courtyard, with that sapling he planted in 1970 now an 80-foot tree towering over it in the center. He took great delight in touring visitors through his home, and visitors came away speechless with wonder at what he showed them.”

The house tour included enthralling (and sometimes bizarre) circus posters, artwork, collections of objects – toy metal motorcycles, tiny airplanes, illustrated canned peaches and plums, wall hangings and more – all on display in every corner of the home, Ulmschneider said.

“A visitor followed him in a winding circular path around the house, mouth agape at the wonder of it all,” he said.

And in a second-floor office, with a cherished large skylight to illuminate the space, Robbins wrote his first drafts by hand on yellow legal pads – which VCU Libraries now preserves. The room was an apt setting for a writer who developed an intimacy with his characters while himself becoming a towering figure.

“For a true honest-to-God celebrity, Tom always seemed quite shy – diffident even – a down-to-earth person. He truly loved his Southern world, and all the characters who inhabited it, with the most natural, genuine and deepest affection,” Ulmschneider said. “I think future generations will recognize Tom as one of the most extraordinary literary stylists of the 20th century.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.