July 1, 2015

From zombie ants to shooting spores, biology course introduces students to all things fungi

Share this story

Fungi have been shooting their spores all over a table in professor Fernando Tenjo’s classroom.

His students gather them up and joke about how “adorable” and “cute” the little reproductive necessities look under the microscope. Few people would use those same words to describe the fungi over by the window. That was scraped off rabbit dung and grows more hideous by the day.

“It’s amazing how many different types there are,” said Jonathan Eden, who just completed his bachelor’s degree in biology. “We’re only dealing with a few. There are so many more out there, and a lot of them are still a mystery.”

Eden and 10 other Virginia Commonwealth University students explored the good, bad and ugly of fungi this summer in a Fungal Biology class. It is designed to answer basic questions about fungi, how they grow, their relationships to humans and more.

Students this summer also had the distinction of employing the latest techniques and technologies in a quest to discover new species of fungi.

“Before this, only a few of them had any experience with this technology,” said Tenjo, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Biology, part of the College of Humanities and Sciences. “Now they all do.”

Numbers game

It is generally accepted that there are about 1.4 million species of fungi. Some experts put the number as high as 5 million to compensate for new technologies that have opened up a world of possibilities in the study of genetics.

Whatever the number, only about 100,000 of these species are officially on the books as having been discovered and described.

The rest, as Eden said, is a mystery.

Tenjo’s course introduces students to the technological advances that are helping to unravel that mystery.

The advent of DNA sequencing, which gives researchers the ability to paint a detailed genetic picture of any organism, has led to more frequent discoveries.

It’s not unusual now to see more than 1,000 new species of fungi discovered in a year. Researchers using DNA analysis recently discovered three new species from a packet of porcini, an edible mushroom.

It sounds easier than it is.

“To describe a species, you still need to grow it in the lab, document their nutritional requirements and other morphological and biochemical aspects that take a lot of time,” Tenjo said. “It may take 1,170 years to describe 1.4 million fungi.”

The rate of discovery will only increase as next-generation sequencing technology improves, Tenjo said, and he wants his students to be part of the action.

The professor began offering Fungal Biology as a special topics course in spring 2012. He has taught the class almost every semester since as a regular course and hopes to be able to make it available to even more students, giving undergraduates the rare opportunity to use the latest technology in the field.

Out with the old, in with the new

A lot has changed since Tenjo began looking at fungi in his undergraduate studies in Colombia during the 1980s.

“We had to look at a fungus on a plate and be able to tell which kind it was,” Tenjo said. “That’s tough. But with this technology, anybody can do it.”

Students use a variety of technologies in the class. Last week, they went about their work in various corners of the classroom performing different experiments.

“He trusts us a lot,” said Dorothy Yen, a senior biology major.

Tenjo provided guidance when needed, but students had mastered many of the processes that were new to them just four weeks earlier.

“That’s been the highlight for me,” said junior biology major Nicholas Kelly as he prepared a slide of spores to examine under the microscope. “I didn’t know anything about fungus, and I like a lot of the things we do in the lab.”

During one experiment, Kelly helped cross two kinds of yeast whose traits complement each other, allowing them to grow in nutrient-deficient environments. It’s one of many experiments students carried out during the lab portions of the course, during which they learn to cut and culture the fungus, isolate and identify it.

A major goal of the course is to teach students the art of amplifying and sequencing DNA from their samples, which come from soil in the James River.

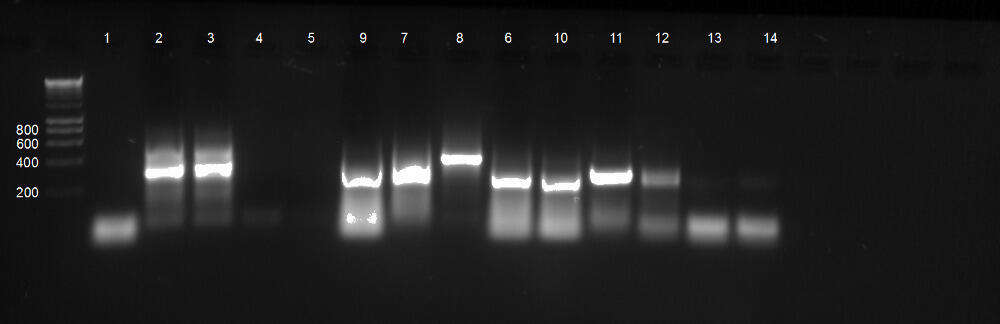

To amplify the DNA, students learned polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, a quick and automated way to make copies of many DNA segments.

One process they used is called agarose gel electrophoresis. Samples are put into a gel made of polymer derived from seaweed and then subjected to an electric current, which separates DNA pieces based on size. Students then put the gel into a machine that produces an image in which DNA is illuminated.

Some of the DNA will be sequenced in the traditional way. Called Sanger sequencing, it was the most widely used method until next-generation technologies began appearing a little more than 10 years ago.

The students also will have samples run through the Department of Biology’s Ion Torrent machine, a next-generation technology that produces thousands of DNA sequences in a matter of hours.

These sequences then will be compared to data for already documented species.

“Some of them might be old, some of them might be new. We will need to get a novel DNA sequence,” Tenjo said. “This is a bit tricky, but comparing to DNA sequences in databases can give us a first approach to a new fungal species.”

A class on fungus?

Tenjo’s course is not required; most students say curiosity drew them to it.

“I just thought it was an interesting topic,” said Angela Park, a senior biology major. “I didn’t know what I would learn in a class about fungus.”

As it turns out, Park and her classmates learned quite a bit in the flash of a summer semester.

On just the second day of class, they went out in the field and collected samples from the James River’s North Bank Trail. On another outing, they talked to a local mushroom farmer about what kinds are safe to eat.

They learned that entire ecosystems can be affected by fungi. For example, certain bats and frogs — both of which help control insect populations — are dying off because of diseases caused by fungi.

They found out that a caterpillar fungus is used like Viagra throughout Asia and learned about fungi’s role in commercial products and medicine. They also discovered how similar fungi and humans are genetically.

“That’s why antifungal medicine is not really good for us,” Park said.

Then there are zombie ants.

A fungus called Ophicordyceps camponoti-rufipedis kills ants and takes control of their bodies, growing a stem from the ant’s head from which it shoots its spores.

Tenjo’s students studied the variety of ways fungi disperse their spores.

The fungi by the window — called Pilobolus — grows toward and shoots its spores at sunlight. To see it in action, students put the fungi in dishes and covered them with tin foil, leaving holes in the top for the sun to come through.

Like their conquering of new DNA analysis tools, it was just one more example of how Tenjo’s students took it upon themselves to put what they were learning about fungi into immediate action.

“I just let them go, and they have been doing all of this on their own,” the proud professor said.

And soon they will know if they discovered any new kinds of fungi along the way.

Featured image up top : Junior biology major Nicholas Kelly prepares to examine a slide of spores under the microscope.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday. VCU students, faculty and staff automatically receive the newsletter. To learn more about research taking place at VCU, subscribe to its research blog, Across the Spectrum at http://www.spectrum.vcu.edu/

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.