Oct. 1, 2020

Going the distance in six years or less

Share this story

The young woman came to the Rams Reconnect event at Virginia Commonwealth University with her parents, clutching a folded letter. The letter was her invitation, sent to a group of former students whom VCU hoped to convince to return and finish their degrees. The students’ common characteristic was being this close to graduating — they were in good academic standing and they’d earned more than 90 credit hours out of the 120 typically required to complete an undergraduate degree.

Despite having nearly completed a college degree, however, these students were stop-outs. The term refers to students who have withdrawn from their institution, often intending to return. Unfortunately, the longer they stay away, the less likely they are to graduate. The Rams Reconnect program identifies good candidates for graduation and helps these stop-outs overcome the barriers blocking them from crossing the academic finish line.

Tomikia LeGrande, Ed.D., vice president for strategy, enrollment management and student success at VCU, remembers noticing the young woman’s discomfort, seeing her mother nudging her. LeGrande introduced herself to the group, telling the students, “Welcome home.” After LeGrande finished speaking, the young woman and her parents walked up to her. The parents said they’d been trying to convince her for two years to come back to school. The young woman, still holding the letter, said receiving it had made her feel she might be ready to try to finish her degree.

“What really seems to be the difference maker for students is when we can show them their degree audit, and they can see how close they are to graduation,” LeGrande said. “Some of them leave and don’t really have a clue of how close they are.”

Their reasons for leaving frequently are financial, and the amounts involved are often both relatively small and incredibly difficult for students to secure.

“On average, those financial barriers are about $800,” LeGrande said.

By the time some students have completed the majority of their degree requirements, they’ve exhausted all readily available sources of financial help. To some students, that $800 might as well be $800,0000. LeGrande argues that helping students overcome barriers of this type can have an outsized impact.

“That $800 investment helps that student increase their earning potential as well as the likelihood of the student being able to give back to the community in a variety of ways,” she said.

Other commonly cited barriers include social and emotional challenges, the need to work, housing instability, transportation issues, military service and child care. Key components of Rams Reconnect are providing completion grants to help students in this situation and offering general advising and financial counseling aimed at creating a plan to clear roadblocks to graduation.

“Just being willing to have thoughtful conversations with the students about the barriers they face helps make them feel VCU cares for them and empowers them to make the decision to return,” LeGrande said, referring to the role advisers can play.

Rams Reconnect, which held its first event in 2019, is still too new to have generated much data on its impact on students’ graduation rates, though at least one participant has now graduated. “We believe that every student who is admitted to VCU deserves a VCU education,” LeGrande said. “Our goal is to understand how we can help the students make that happen.”

Recognizing ‘the reality of students today’

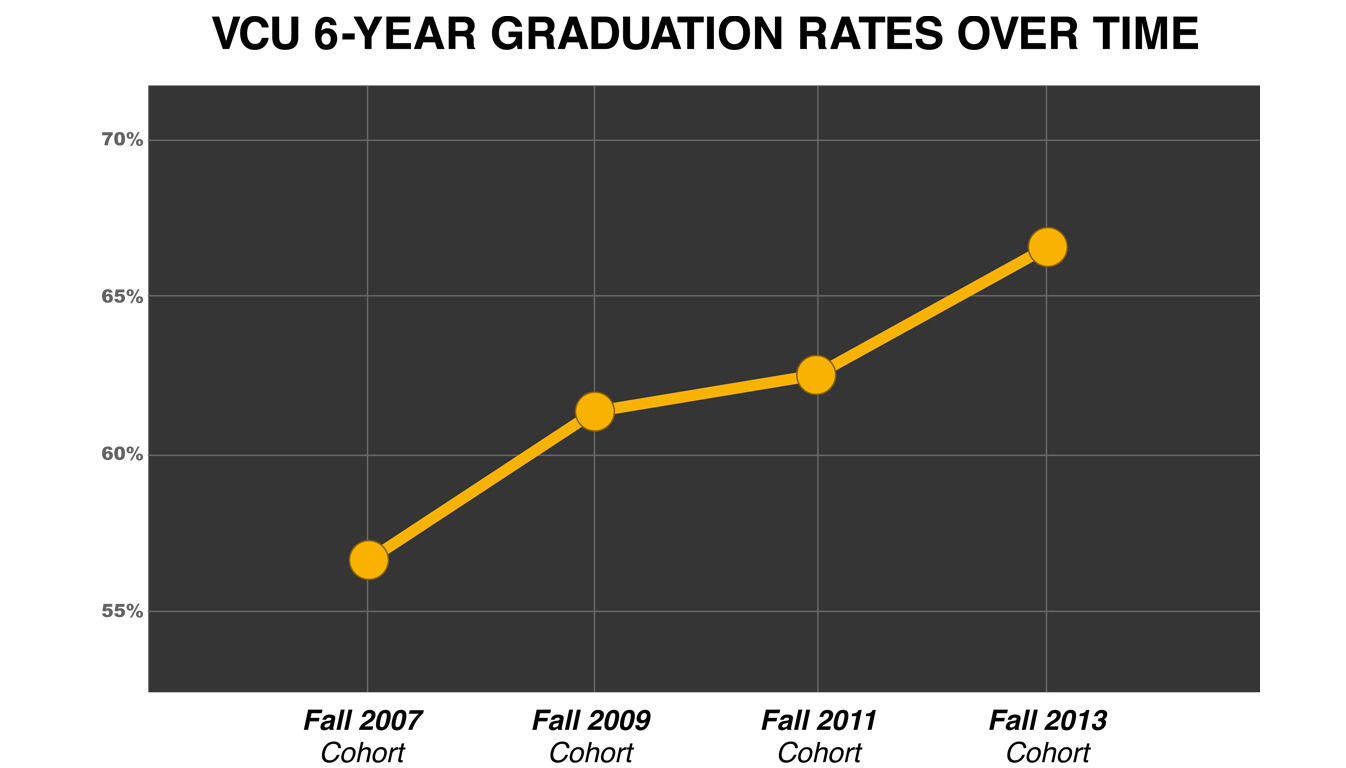

Universities evaluate their success at helping students graduate by measuring what percentage of enrolled students complete their degrees within four years and six years. Since 2013, VCU’s four-year graduation rate has increased by 31% and its six-year graduation rate by 19%. The current four-year graduation rate is 48.2% and the six-year graduation rate is 67.6%. Both rates now exceed the national averages recorded by the National Center for Education Statistics: an average 43.7% four-year graduation rate and 62.4% six-year graduation rate for students who started college in 2012.

Connected with this, VCU has narrowed the difference between its average overall graduation rates and the graduation rates for traditionally underserved groups, including minority and low-income students. For minority students who entered college in fall 2013, the six-year graduation rate is 67.7% — slightly higher than the overall average. Data from students who entered VCU in fall 2013 shows that students who received the Pell Grant — federal aid awarded to lower income students — had a six-year graduation rate of 63.2%.

While both the four-year and six-year rates are important indicators of how well an institution is serving its students, some experts believe that improving the six-year graduation rate is particularly significant for ensuring that nontraditional and underrepresented students succeed.

“We want to recognize the reality of students today,” said Leanne Davis, assistant director of applied research at the Institute for Higher Education Policy, a national organization that aims to improve college access and success for students, with a particular focus on underserved populations. Davis notes that those underrepresented groups include students of color, lower-income students, parents and veterans, many of whom often change from attending full time to attending part time, or stopping out and returning.

VCU’s improvements in six-year graduation rates, Davis said, is “a notable accomplishment for the institution, and it’s much higher than the national average for universities as a whole and also for public universities.”

Helping students graduate on time, LeGrande says, involves understanding how students have changed. “Students are different than they used to be 40 years ago,” she said.

The traditional image of college students — enrolled full time, living in a dorm, focused entirely on studying and academic success — doesn’t fit much of VCU’s student population. For example, VCU’s residence hall capacity is 6,234, meaning the majority of students don’t live in dorms. A third of VCU’s students are first-generation college students, and these students are more likely to report financial stress and pressure from family expectations. More than 50% of undergraduates are minorities, many of whom are affected by historical income gaps and have fewer family resources to pay for college. About a third of students are eligible for Pell grants, which signals that they’re lower income. LeGrande added that many students have families depending on them, including younger siblings, elders or children, and that this can require a student to juggle multiple and competing priorities.

“When you think about the confluence of those factors, what you realize is that our students don’t work just because they want to, they work because they have to,” LeGrande said. (In 2017, 45% of VCU seniors worked more than 10 hours off campus, on par with the national average for students in urban institutions).

The more other considerations pull on students, the more likely it is that at some point “life happens,” putting a goal of graduating in four years (or ever) out of reach. The key to preventing stop-outs, LeGrande said, is to focus on improving student success throughout students’ time at the university. To improve the six-year graduation rate, you have to improve the four-year graduation rate, she said, noting that it doesn’t work well to wait until someone is at risk of not graduating before taking action. To improve the four-year graduation rate, you have to build foundations for success as early as possible in a student’s experience.

Planning for success

To understand how VCU has improved its graduation rates, it’s important first to understand why the effort matters and how graduation rates connect to the mission of making sure that a high-quality education is available to as many students from as many walks of life as possible.

Obviously, most students start college hoping to earn a degree. Likewise, an institution wants to help them achieve their dreams. What can be less obvious are the obstacles that pile up when students don’t finish or take longer to finish. Stopping out could mean a student has a large debt load without the increased opportunities that a degree brings. Even if a stop-out is intended to be temporary, if it lasts more than six months, loan repayments become due, increasing financial barriers to degree attainment.

But when an institution says it wants to increase graduation rates (also called completion rates), that could mean very different things, said Mikyung Ryu, Ph.D., director of research publications for the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

“There are two opposing methods to increase college completion rates. One way would be, institutions do a better job retaining students and helping them to graduate in a timely manner,” she said. “Or institutions could become more selective and make it harder for at-risk students with lower chances of graduating to be accepted.”

In other words, one way to increase graduation rates is to identify students, when they apply, who are likely to face challenges — and avoid the risk for both the institution and the students by not accepting them. Though Ryu does not recommend this approach, she notes that it could increase an institution’s measures of student success.

LeGrande says she’s proud that VCU has chosen to take a different path, readily enrolling students who are underrepresented in higher education. “The beautiful thing about VCU is there is clearly a commitment to access, success and excellence,” she said. VCU enrolls more underrepresented students than many institutions with similar admissions standards and graduates them at higher rates.

“I think what VCU has proven is students who the nation has identified as succeeding at lower rates than their peers can be just as successful under the right set of conditions,” LeGrande added. “You don’t lessen rigor at all, but it means you have to think about what those students’ needs are and then build structures of support for all students based on that.”

The pillars of that support are guidance, financial assistance and engagement, LeGrande said.

VCU interprets guidance to mean much more than the traditional concept of academic advising. Guiding students well, LeGrande said, means going beyond explaining what courses to take to graduate with a certain major. At VCU, advising also addresses what skills students need outside the classroom, what experiences students should have during their time at VCU and determining whether they’re pursuing majors that are a good fit.

One path to success involves technology.

“So many students don’t know they’re in trouble until it’s too late, so we use technology to identify through predictive analytics what are behavioral characteristics and risk factors that anticipate you might have trouble along the way,” LeGrande said. That helps identify students who may need interventions from advisors and mentors.

While financial assistance can include direct aid, such as the completion grants that have helped some participants in Rams Reconnect, as well as scholarships created through private philanthropy such as the Invest in Me initiative, VCU is also revamping systems to make it easier for students to avoid financial trouble. A new initiative assigns every student a financial counselor paired with an academic adviser.

“There shouldn’t be a question that cannot be answered between the two,” LeGrande said.

VCU is also redesigning billing so students can more easily see and understand how they’re being charged for their education. Finally, a new Student Financial Management Center partnered with other campus departments focuses on financial wellness, helping students budget their money and gain financial literacy.

Engaging students is the final, and perhaps most important, piece. “The classroom is the true meat of where the academic enterprise takes place, and so engagement with faculty members is really important for our students,” LeGrande said, noting that students who are engaged in the college experience — participating in classes, invested emotionally in their institution and committed to earning good grades, among other markers — graduate at higher rates.

Despite being a large institution with more than 30,000 enrolled students, VCU ensures all students have opportunities for more personalized attention. For example, VCU’s seminar-style Focused Inquiry courses are a part of the core curriculum and have an average class size of 19, which gives students ample opportunities to participate, interact with each other and benefit from the attention of faculty. VCU REAL connects students with faculty mentors and gives them a chance to see how what they learn in the classroom applies in other situations.

I think what VCU has proven is students who the nation has identified as succeeding at lower rates than their peers can be just as successful under the right set of conditions. You don’t lessen rigor at all, but it means you have to think about what those students’ needs are and then build structures of support for all students based on that.

More work ahead

VCU has more work to do, though, LeGrande said. For example, men of color still experience a significant gap when it comes to graduation rates. The six-year graduation rate for men of color who started at VCU in 2013 was 58.1%.

VCU leadership is working on an implementation plan to help men of color. “We have to connect these male students with their real purpose in being here,” LeGrande said. Male students, she says, sometimes weigh current obligations and earning potential versus longer-term goals of investing in themselves by earning a degree. This can prevent male students of any racial background from becoming fully engaged in the college experience. Any effort to help more men of color graduate, LeGrande said, must overcome this and other societal issues by going beyond focusing on academics. Institutions must also consider issues such as financial needs, support structures and a sense of belonging in the community.

Theodore Evans, an African American student on track to graduate with a major in pre-med biology and a minor in chemistry in fall 2021, says opportunities to connect at VCU have made all the difference for him. His college journey began in 2008 in South Carolina, and along the way, he struggled to stay connected with various institutions while juggling work and other obligations. “I was often in college aimlessly,” Evans said, “just taking courses because they’re telling me to take courses.”

He came to VCU in 2018, and even then, he didn’t know how to take advantage of resources at the institution or how to develop his skills to study, have resilience and find motivation. The connections he’s found at VCU have helped him stay engaged, fill in gaps in his knowledge and make real progress toward the degree he’s sought for so long, he said. He credits Daphne Rankin, Ph.D., associate vice provost for strategic enrollment management, and Alvin Bryant, assistant director of undergraduate advising, with getting him involved at VCU. He now participates in peer mentorship and organizations including Black Men in Medicine at VCU, where he’s eager to help other students find the connection he has.

Despite the successes VCU has had so far, the COVID-19 crisis and accompanying economic impacts raise some questions for the future.

During a recession, says Ryu of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, more high school graduates attend college because of a lack of job opportunities. This can increase the population of students who face challenges, and institutions might need to devote even more resources to ensuring their success.

LeGrande believes VCU can and will continue to offer students the complete package of access, success and excellence.

“Our goal for 2025 for student success is to get to where the nation’s most selective institutions are,” she said. As of 2019, highly selective institutions reported about a 57% four-year graduation rate and about a 76% six-year graduation rate on average.

“Think about the narrative when VCU gets to that place and can show the nation that student success is not predetermined by who you exclude but, more importantly, student success is determined by who you include and by creating the right set of support conditions designed with them in mind,” LeGrande said. “That takes educational equity to a whole different conversation.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.