Feb. 26, 2016

New book edited by VCU professor tells story of freed Virginia slave’s journey

Share this story

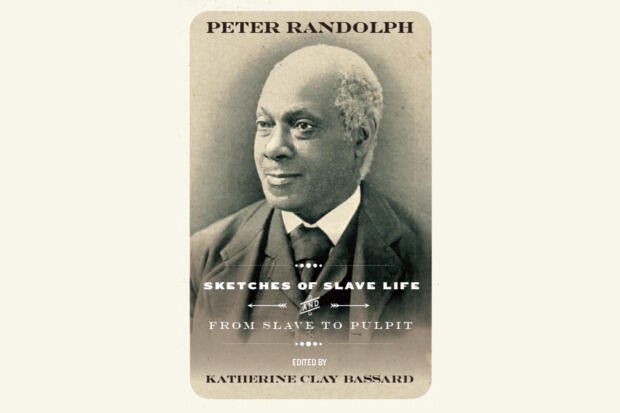

A Virginia Commonwealth University professor has edited the first anthology of the autobiographical writings of Peter Randolph, a 19th-century former slave from Prince George County, Virginia, who became a prominent abolitionist, pastor and community leader.

“Sketches of Slave Life and From Slave Cabin to the Pulpit” (West Virginia University Press), edited by Katherine Bassard, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of English in the College of Humanities and Sciences and VCU’s senior vice provost for faculty affairs, offers a window into Randolph’s experience of enslavement, emancipation and freedom.

Who was Peter Randolph, and what was his story?

Randolph was a prominent 19th-century African-American pastor, community leader and author. He is the author of three autobiographical writings, “Sketches of Slave Life” (two editions in 1855) and “From Slave Cabin to the Pulpit” (1893). He began life enslaved on the plantation of Carter H. Edloe in Prince George County, Virginia, who freed Randolph along with the entire plantation workforce upon his death in 1844. Three years later, after a number of legal obstacles, 66 former Edloe slaves were transported to Boston, Massachusetts, along with nearly $15 apiece as stipulated in the will. In 1855, at Randolph’s leading, the group launched a lawsuit from Boston against Edloe’s estate for the remainder of their “inheritance” (they were supposed to get $50 each). Their suit was successful and resulted in the preservation of documents that corroborate and illuminate Randolph’s writings.

Why do Randolph's autobiographical writings remain important today?

Randolph’s writings are what I call “emancipation narratives,” which interrogate the categories of “enslaved” and “free” identities in more nuanced ways than the abolitionist-sponsored fugitive slave narratives. The fugitive slave narrative (for example, Frederick Douglass’ “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave,” 1845), featuring self-emancipated individuals, has served as the dominant paradigm for our understanding of African-American agency and self-determination.

In Randolph’s case, being freed by last will and testament and with an entire plantation cohort led to a series of negotiations of the terms of freedom as a process rather than a singular event. I think the success of the film version of Solomon Northup’s “Twelve Years a Slave” similarly hinges on expanding our views of the complexity and fluidity of enslavement and freedom for 19th-century African-Americans.

What sets Randolph's experience of slavery and freedom apart from other narratives?

They lived in close proximity, held jobs as waiters, domestics and laborers in common spaces, worshipped together and mourned together.

Not only was it rare for enslaved African-Americans to be emancipated by will (about one in 1,000), I know of no other case where the group used legal means to sue and win a claim against the deceased master’s estate. This is an extraordinary display of agency and solidified the claim to freedom. “Sketches” has been quoted for its vivid description of African-American communal life — especially religious culture — in the 19th-century South.

What I found fascinating is the way that this community in the court records emerge as intact family units (their surnames, for example, appear for the first time in the preface to “Sketches”) and held together to face the vicissitudes of life in freedom. They lived in close proximity, held jobs as waiters, domestics and laborers in common spaces, worshipped together and mourned together. This challenges the notion that African-American family and community was completely destroyed by slavery. The individual and communal resilience of this group is remarkable and admirable.

What do you hope readers get out of reading Randolph's autobiographical writings?

I hope that readers will emerge with the sense that slavery involved millions of people over centuries of time and that it will spark a desire to hear as many different stories and narratives as we can uncover, document and research. All of the stories of slavery have not been told and the vast majority are unrecoverable. But each one that we uncover teaches us something we didn’t know before.

How does this new book fit within your larger body of scholarship?

My work in early African-American literature has been a journey of bringing to life a silenced and often buried past. My work has focused primarily on early African-American women: “Spiritual Interrogations: Culture, Gender and Community in Early African American Women’s Writing” (Princeton University Press, 1999) and “Transforming Scriptures: African American Women Writers and the Bible” (2010).

Lately, I have become fascinated by the material that remains in the archives. Randolph’s writings led me to the manuscript of Fields Cook, a prominent 19th-century barber, entrepreneur, Reconstruction activist and pastor, who left an unfinished manuscript of his memoir dated in 1847. It is the only manuscript in existence written by an African-American while still enslaved in the South. I am currently working on a digital edition of Cook’s manuscript, “A Sketch of My Own Life: Manuscript of an Enslaved Virginian,” with my English department colleague Joshua Eckhardt, Ph.D., through British Virginia.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.