Aug. 10, 2020

New murals, including this one co-created by a VCU alum, inspire conversation about Black Lives Matter

Share this story

Two portraits bookend a new mural in the Virginia Museum of History & Culture. To the left, a woman stares into the distance, her flowing locs adorned with the symbols recounting the history of oppression of African Americans. A cowrie shell representing Afrocentrism leads to images of shackles and slave ships and then to the clenched fist symbolizing the Black Power movement and today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

On the opposite end, a man smiles out at visitors, a halo of chemistry and biology symbols surrounding his face.

The background is filled in with patterns reminiscent of Greek pottery, painted in the earth tones typically associated with Africa. At the center is the figure of a bird, its head turned to face backward. The bird, known as Sankofa, is a metaphorical symbol for understanding the knowledge gained in the past and bringing it to the present in order to make positive progress.

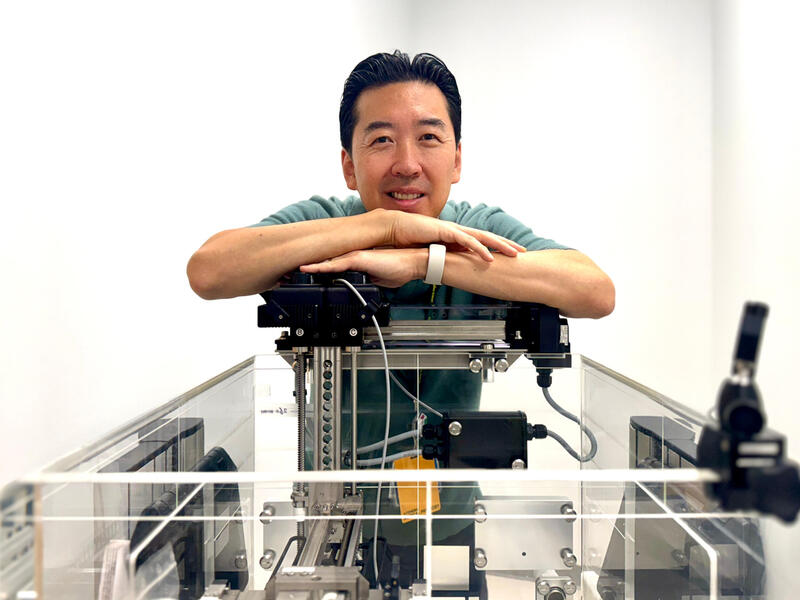

The intertwining symbols represent the history of oppression and adversity faced by African Americans — and the perspectives and aesthetics of the two Richmond artists who created the mural: Ian C. Hess, a Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts alumnus who co-founded Endeavor RVA, and Jowarnise Caston, a visual artist and designer known for her naturalistic portraits of women in eloquent poses.

“In a way, the symbols tell a story,” Hess said, “but also cast a vision forward that we may aspire to.”

The mural is one of several public art projects organized through Mending Walls, a public art project conceived by Richmond muralist Hamilton Glass, following the killing of George Floyd in May. Glass noticed Floyd’s death captured more attention than previous incidents of police violence, and started having conversations with white friends to get their insights into why it was different.

At the same time, Glass was struck by the resulting protests around Richmond, and struggled to watch spray-painted tags on buildings simply washed off and painted over.

“Instead,” he said, “we need to further the conversation of those voices who feel unheard. That’s why those tags are on the wall in the first place.”

Glass approached the Community Foundation with his idea for Mending Walls: pairing artists from different cultures and backgrounds to create murals that contribute to the Black Lives Matter conversation, while also creating space to find healing through personal connection. The project launched the next day.

So far, Mending Walls has seen four artist pairings, including Caston and Hess, and Noah Scalin, the inaugural VCU School of Business artist-in-residence, and Alfonso Pérez Acosta.

Hess and Caston’s conversation began with finding a way to blend the perspectives and messages they each wanted to convey. Caston wanted to talk about generational and historical trauma, as well as the Crown Act, a new Virginia law that prohibits discrimination against natural hair in schools and workplaces. Hess was interested in how mental health intersects with police violence, and wanted to include a memorial portrait of Marcus-David Peters, a Black man who was killed by Richmond police while experiencing a mental health crisis.

Then they sought to blend their aesthetics — merging graphic design and fine art, and commingling Greek, Egyptian and African symbols.

“The mural design was a process of taking our strengths and combining them in a way that illuminated the sensitive topics we both wanted to talk about,” Hess said.

Caston added, “Much like our similarities and differences of our artistic styles, our approach to creating this mural centered on our similar desire to encourage equitable change to end traumatic reoccurrences, but different in how and what experiences we wanted to portray. We were challenged to overcome our creative differences to cohesively express our ideas.”

The process of connection is just what Glass had in mind — and what he hopes visitors to the mural will take away from their observations. He also plans to keep the conversations going through a documentary, podcast series and civic talks.

“The real idea was to get artists from different backgrounds together to have those tough conversations, but also to inspire empathy and connection between the two, and then between those who are digesting the work,” Glass said.

“In these heightened times that we’re in, we all say stand for, but what you stand for can look differently to different people. Black Lives Matter means different things to different people. Mending Walls honestly stands at a place where both sides need to be heard and empathize, because that’s where the real change is going to happen.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.