Aug. 24, 2018

Social work students explore Richmond history at the intersection of race and mental health

Share this story

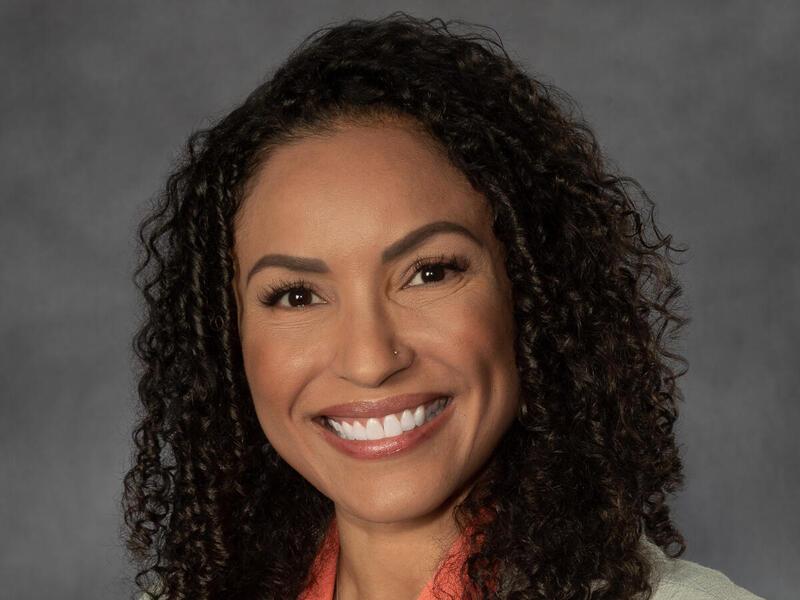

Princess Blanding, sister of Marcus-David Peters, a 24-year-old black man shot and killed by a Richmond police officer in May, stood before a crowd of Virginia Commonwealth University School of Social Work students, faculty and alumni.

Her message: People experiencing mental health crisis deserve help, and we need to break down the stigma preventing them from getting it.

“Think about some of those words that prevent a whole lot of us and our family members and our friends from actually saying, ‘I need help. I'm going through something,’” she said. “The brain is the only major organ in our very complex system that, when it is in distress, we ostracize them, we pass judgment on them, we treat them as outcasts.”

Peters, a high school biology teacher and VCU graduate, was unarmed, naked and undergoing what Blanding described as her brother’s first mental health crisis on May 14. As he charged the police officer, the officer tried unsuccessfully to stop him with a Taser, and then shot him.

“Marcus needed help,” Blanding said. “He didn’t need, nor did he deserve, death.”

Blanding was a keynote speaker Tuesday at “Richmond [Re]Visited 2018: The Intersections of Race & Mental Health,” an event organized by the VCU School of Social Work Black Lives Matter Student-Alumni-Faculty Collective that explores Richmond’s history and provides context for issues affecting social workers and community members.

The event, now in its fourth year, focused on a theme of mental health and racial justice.

M. Alex Wagaman, Ph.D., a member of the collective and an assistant professor in the School of Social Work, said the goal of this year’s event was to help participants — students, faculty, staff and alumni — gain a “better understanding of the ways in which our country's history of violence toward people of African ancestry is a form of intense trauma that has never been healed.

“We want social workers to understand the systemic and community context necessary for mental wellness, including the ways in which social work has upheld white supremacy,” Wagaman said. “And we want everyone to identify ways that they can practice social work through a racial justice lens, including the dismantling of white supremacy in our communities and the organizations where we work.”

![M. Alex Wagaman, Ph.D., assistant professor in the School of Social Work, and Daryl V. Fraser, associate professor in teaching in the School of Social Work, introduce the students to Richmond [Re]Visited 2018: The Intersections of Race & Mental Health.](/image/408bc4b8-0150-47e1-b743-d2d3855fecc3)

A deeper understanding of racial justice

Richmond [Re]Visited aims to introduce or reintroduce future social workers at VCU and others in the social work community to Richmond’s long and troubled history of segregation, discrimination, and racism that still permeates the city’s neighborhoods, schools, jail and businesses.

Over the past four years, Wagaman said, the event, along with year-round efforts by the School of Social Work Black Lives Matter Student-Alumni-Faculty Collective, has deepened students’ understanding of racial justice and prepared them better for a career serving the community.

“Students and faculty have felt more empowered to learn about and discuss issues of racism and racial justice in their classrooms, field placements and assignments,” she said. “Our relationships to, and with, community leaders doing racial justice work has deepened. And our school as a whole is developing a sustained commitment to racial justice.

“I also have seen our graduates enter the profession with more confidence in their capacity to do racial justice work,” she added. “The sustained involvement of our alumni in the collective also tells us that the work is important. It gives people a space to learn and be nurtured in this work.”

This year’s theme was inspired by last spring’s Cultural Awareness Day hosted by the VCU Association of Black Social Workers. The keynote speaker, King Davis, Ph.D., a former commissioner of behavioral health and developmental services for the state and emeriti faculty of the School of Social Work, discussed his research on Central State Hospital, originally known as Central Lunatic Asylum, the first mental institution for blacks in America.

“The members of the Black Lives Matter Collective who were in attendance were particularly struck by the historical evidence he had of the ways that criminality and mental illness were used to characterize formerly enslaved people post-Emancipation Proclamation,” Wagaman said. “In fact, there were documents written that stated that black people would not be able to handle freedom — that liberation would make people mentally ill. This was a turning point in the new forms of enslavement that we see today in the form of mass incarceration and over-institutionalization of black people in this country.”

Public housing and mental health

As part of Richmond [Re]Visited, participants took a bus tour of sites in Richmond that shed light on the city’s history.

Along the way, collective members Daryl V. Fraser, associate professor in teaching at the School of Social Work, and second-year doctoral student Keith Watts pointed out relevant points of interest, such as the gentrifying Highland Park neighborhood, the Richmond City Justice Center, Interstates 95 and 64 — construction of which displaced black neighborhoods — and public housing developments Gilpin Court and Whitcomb Court.

“Please note the proximity of all the public housing buildings to the juvenile detention center and the Richmond City Justice Center,” Fraser said. “They are all within approximately 1 mile of each other.”

That proximity, Watts added, affects the mental health of public housing residents.

“Your whole community is reminding you to constantly be worried about: ‘Am I going to go to jail?’ ‘Is my friend going to go to jail tomorrow?’” he said. “And all of these neighborhoods have an elementary school in the middle of them. When you think about the context of mental health, if you live in this community, if your school is there, you never have to leave. And all you see is courthouses and police and jails. It's a constant reminder of this oppressed life that you have. Just think what that does to the mental health of a child.”

Post-traumatic slavery syndrome

At one stop, the participants visited Great Shiplock Park on the James River, where the Rev. Sylvester L. “Tee” Turner described how the park is near the site of what was once a slave market and the epicenter of Virginia’s slave trade, the second-largest in the United States.

Turner, a longtime community leader and advocate for Richmond’s slave trail, said gaining a better understanding of post-traumatic slavery syndrome is key to understanding the context of issues facing Richmond today.

“You can't really talk about post-traumatic slavery syndrome and not really deal with internalized oppression, not deal with implicit bias, not deal with white privilege. Because all of those things come into play and all of those things sustain that institution,” he said.

“I'm passionate about this history and I'm passionate about how this history is impacting us today,” he added. “The more I do this work, the more I realize that we're all ignorant of this history. And if we're ignorant of the history, we'll always be ignorant of the true impact that it has in our lives.”

For example, Turner said, the language of the institution of slavery — most notably calling an enslaved person a “slave” — perpetuates the false narrative, even today, that black lives do not matter.

“When we talk about ‘slaves,’ slaves were considered to be three-fifths of a human. Anything that's three-fifths of a human is subhuman. If you're subhuman, you're not human, you're a beast. And if you are a beast, you are a threat. And if you are a threat — perpetuated through different laws and the media — then it's easy for someone to confuse a cigarette lighter for a gun and shoot you,” he said.

“That's part of what Black Lives Matter is really all about,” he said. “It starts in our subconscious when we perpetuate the term ‘slaves.’ So we have to remove that term from our vocabulary. And, by the way, W.E.B. DuBois said we're either part of the problem or we're part of the solution. So we can’t change what happened, but we can change the narrative of what happened.”

Racial trauma and healing

At another stop, the Richmond [Re]Visited participants heard from Jacqulyn "Jackie" Washington, an alumna of the School of Social Work and center director of the nonprofit Six Points Innovation Center, and Lillie A. Estes, a VCU alumna and community strategist at the Peter Paul Development Center in the East End.

Washington encouraged the group to understand how mental health is affected by issues at the community and individual level. For example, she said, when a historically black neighborhood is experiencing gentrification, it sparks a great deal of fear and anxiety.

“And now you see the mental health come into play,” she said. “The fear of not being able to afford the home you've lived in 40 years because of tax increases, for a black person that is triggering a lot of generational trauma.”

That trauma, she said, traces back to slavery. “Black people were already removed from their home literally and brought over to be enslaved.” And more recently, many residents and businesses of the Jackson Ward neighborhood were displaced to make way for the highway.

“Again, you are taking a group of people and removing them from their space,” Washington said. “Now we have all these conversations about gentrification, rising rental properties, so maybe you're not even a homeowner, but your rent is going up. A lot of it is intrinsically tied into greed and capitalism and white supremacy.”

Washington also said that many historically black neighborhoods in Richmond have suffered decades of racial trauma, dating back to the era of redlining, in which black neighborhoods were essentially shut out from mortgage lending, cutting families off from capital and reinforcing urban poverty.

At the same time, she said, Richmond is filled with organizations such as the Peter Paul Development Center that are working to promote healing of racial trauma.

“This is a healing space that realized that the East End was directly affected because of racism. It is experiencing a lot of trauma, rates of violence are high, life expectancy is low,” she said. “Families in the East End can come here and heal. They can learn, they can learn skills, they can be involved in decisions that are happening.”

Reducing stigma

In speaking to the Richmond [Re]Visited audience, Blanding said she wants the future social workers to understand the urgent need to reduce the stigma of mental health care.

“What happens is people don't tell anybody” when they are experiencing a mental health crisis, she said. “Words such as ‘crazy,’ ‘bipolar,’ those are some of the things we hear. Very heavy in the black community. If people were to insinuate that something is a little off with you, [people will say] you're crazy, don't deal with that person.”

She urged them to keep her brother’s story in the back of their minds in their work as social workers.

“How can you break down that negative stigma so that people, if they're going through something, they'll feel comfortable enough to say, ‘Hey, I need help?’ And it's OK to need help because it's kind of like a balloon effect. We try to hold it in and hold it in and we keep trying to deal with it [on our own]. But what happens if you pump too much air in the balloon? It's going to explode.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.