Dec. 14, 2018

Students uncover stories of enslaved people who lived and worked at Richmond’s Wilton House

Share this story

Much is known about the history of Richmond’s Wilton House, which was built in 1753 and home for more than 100 years to Virginia’s prominent Randolph family.

It hosted George Washington shortly after Patrick Henry delivered his “Give me Liberty, or Give me Death!” speech during the Second Virginia Convention in 1775. And then-governor Thomas Jefferson visited the Marquis de Lafayette and his 900 troops camped there in 1781 before they helped secure American independence at Yorktown.

But much less is known about the identities and daily lives of the enslaved people who lived and labored at the 2,000-acre tobacco plantation.

This fall, a class of six Virginia Commonwealth University graduate students in the Department of History in the College of Humanities and Sciences conducted extensive research on Wilton’s enslaved community on behalf of the Wilton House Museum.

“At Wilton House Museum, the star of their tour has always been the house itself. They want to be able to tell the stories of all the people who lived and worked there, including the enslaved people who did all the labor,” said Sarah Hand Meacham, Ph.D., an associate professor who specializes in colonial American history. “We wanted to find their individual stories, and to learn about their lives and experiences.”

Last week, students in the class, Research in Early American History, presented their findings at the museum, paving the way for Wilton House to showcase the research.

“We were incredibly impressed with the students’ professionalism in their presentations and quality of their original research,” said Katie Watkins, director of education at Wilton House Museum. “[We] will be incorporating elements of the students’ research into our daily programming and tours, as well as including it in our long-range interpretive plan. Their work greatly expands our understanding of the complicated relationship between the Randolphs of Wilton, the enslaved community that lived there, and the family as a whole.”

One student researched what happened to a group of enslaved men and women who were meant to be freed in 1840. Another focused on burial practices of the enslaved people in the colonial era, and where the Wilton slaves might be buried. Yet another investigated the region’s enslaved people’s healthcare practices at the time.

The students combed through archives, Meacham said, including those at the Library of Virginia, the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Special Collections at Swem Library at the College of William and Mary, the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg, and the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

“They have tracked down coroner's reports, they have tracked down court of chancery reports. They have had moments of panic that they wouldn't find anything. They have had plan B, plan C and plan D,” Meacham said. “And they have all done remarkable work researching the enslaved community here at Wilton House and what their days and what their lives were like.”

One of the students, Ana Edwards, looked into the story of Robert Cowley, a mixed-race man who was a slave owned by Peter Randolph, brother of William Randolph III, who built Wilton House.

Cowley, Edwards found, was freed in 1785. He served as doorkeeper of Virginia’s state capitol, a job that was awarded to him along with a house and a salary of $200 for service — details of which are unknown — during the Revolutionary War.

Being mixed race, Cowley had been rumored to be the son of a prominent Virginia family, possibly Peter Randolph. Edwards, however, presented evidence that Cowley may instead have been the grandson of a white woman, an indentured servant name Anne Colley.

“I came across a book called ‘Free African-Americans of Virginia and North Carolina,’” Edwards said. “In that book, it’s an extensive listing of free black people in the colonial era. I came to a page with the name Colley, and it told the story of a white woman who was an indentured servant to a woman living in Westmoreland County. Her name was Anne Colley. And she was brought up on charges of giving birth to a child out of wedlock who was a mixed-race child. That child would have grown up and been roughly the same age as Robert Cowley.”

The book lists six people who may have been descendants of Colley, including a man with a name similar to Robert Cowley who was described as the doorkeeper at the state capitol.

Cowley was also notable for having been accused of being involved in Gabriel’s slave rebellion, but was exonerated. However, details of his alleged involvement and exoneration seem to have been lost, Edwards said.

Another student, Peighton Young, researched four slave owners from the Randolph family who chose to manumit — or free — large numbers of African Americans between 1783 and 1859 at a time when free black people were considered a danger to white Virginia society.

“Due to the anti-black sentiment that pervaded Virginia and American society during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the act of manumitting was frequently hindered by legal setbacks in terms of restrictive legislation, for social and political hostilities, and could be extremely costly monetarily,” Young said.

Each of the Randolph men involved in Young’s study were found to have some degree of anti-slavery sentiment and held some sympathies regarding implications of enslavement. However, she found, the fact that these men chose to manumit did not necessarily lead to a positive end on the part of the African Americans who were manumitted.

Jacob Randolph of Isle of Wight County freed 16 slaves during a wave of anti-slavery sentiment following the Revolutionary War. “I have yet to find additional records detailing what happened to those 16 people beyond their names, ages, and health statuses as the time of their manumissions,” Young said.

In the case of Richard Randolph of Bizarre, he manumitted a number of slaves who — albeit 15 years after his will mandated their manumission — went on to start a free black community on land provided by Randolph’s estate.

Yet in two other Randolph family manumission cases Young studied, the cases were so botched that the formerly enslaved people received little to no protection or benefits they were supposed to receive under the Randolphs’ last wills and testaments.

“Some of those who were manumitted met with threats of violence and land theft shortly after being manumitted,” she said. “Ultimately, I think my conclusion of manumission culture in Virginia is fairly negative. It was by no means guaranteed to be successful, even if it was supported by members of Virginia’s elite, and frequently ended in additional hardships for the formerly enslaved.”

Eric Szandzik, a student in the class and a financial analyst in VCU’s Office of Research Administration, analyzed Wilton House’s finances.

“I analyzed the financial trends and state of affairs for the Wilton House by utilizing eight documents: Peyton Randolph's will from 1784, Henrico and Powhatan tax records from 1790 and 1801 (four documents), William Randolph IV's will from 1815, and Anne (Andrews) Randolph ‘Executive Account’ (an accounting book) which ends in 1821, and a descriptive letter about the house from 1833,” he said.

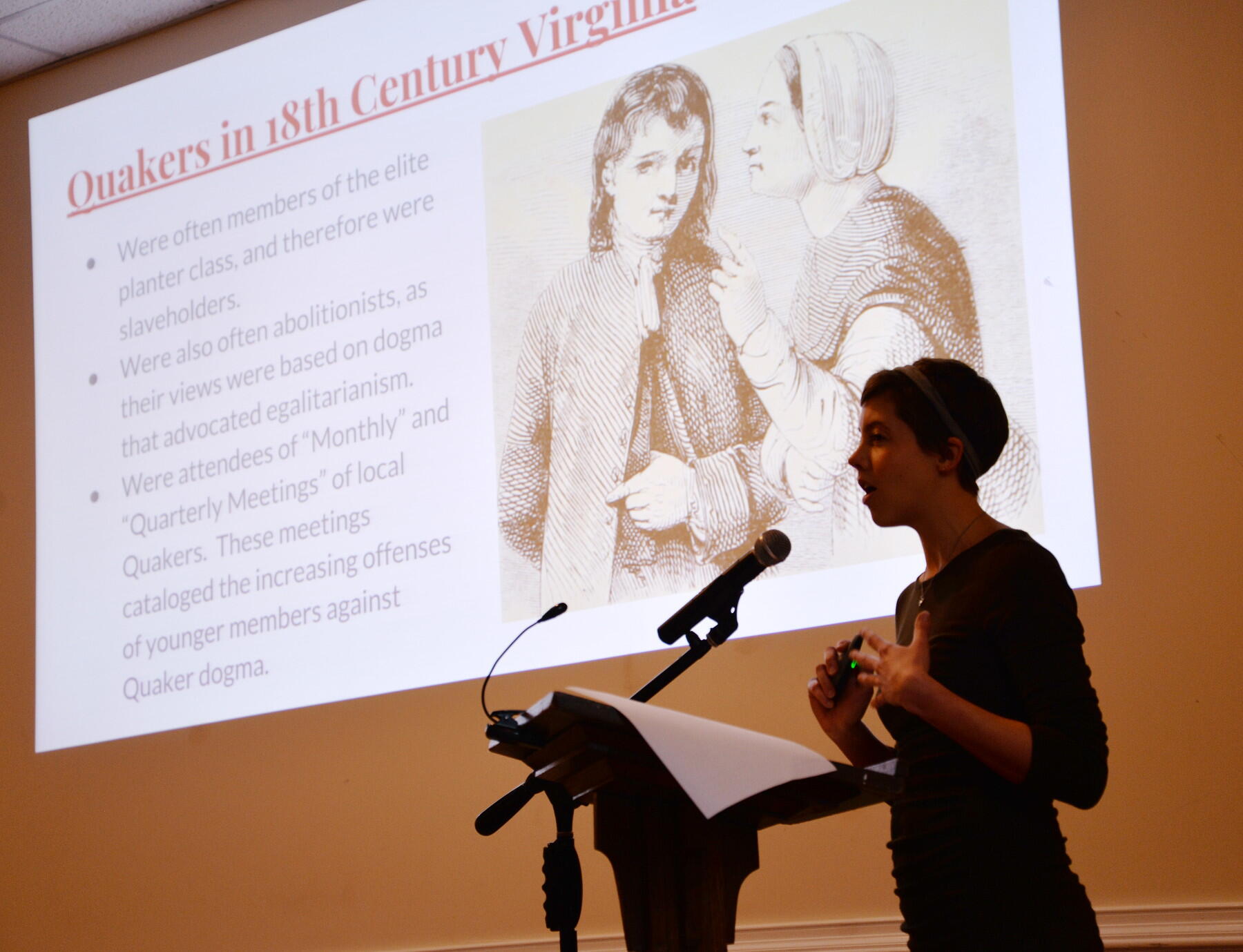

Yet another student, Alexandra Zukas, focused on Robert Pleasants, a Quaker merchant and planter from Henrico County.

“Pleasants was both a slaveholder and an abolitionist, which seems to have been rare, but not nonexistent, surprisingly,” Zukas said. “Before 1782, it was very difficult to free slaves in Virginia; slaveholders had to petition the Virginia General Assembly for permission to do so, and it wasn't always granted.”

In 1782, the Virginia General Assembly made it legal to free slaves via will.

“This comes into play in Pleasants’ story because his father, John Pleasants, had put a stipulation in his will that all inheritors of his slaves (Robert and his siblings, as well as some nieces and nephews) were to free those slaves if it ever became legal to do so,” Zukas said. “Robert Pleasants freed his slaves in 1782, but his family members (all Quakers who initially claimed to be pro-emancipation) refused to do so. He took them to court in order to force them to honor the will, and eventually over 400 slaves were freed because of the case.”

Pleasants’ story ties into the Randolph family because he represented one of the Randolphs’ slaves, Aggy, in her fight for freedom.

“When Ryland Randolph of Turkey Island passed away, he had manumitted Aggy and her children in his will and given them an inheritance; of course, Randolph’s relatives refused to execute the will, so Aggy had to go to court to obtain her freedom,” Zukas said. “I originally intended to study her in my paper, but I became really interested in Pleasants, and in particular the way that Quakerism interacted with abolitionism, the culture of the South, and the ideals of the American Revolution.”

Meacham said she is proud of her students’ work to tell the stories of the enslaved community at Wilton and related sites, helping provide a more complete understanding of Virginia’s history.

“In Virginia, a lot of fourth graders go on field trips to historic sites in Virginia like Wilton House as part of their Virginia studies curriculum,” she said. “When it comes to a project like this, I think about how a fourth grader can understand such large movements in history. And one way to do that is to tell very specific stories, very specific narratives that allow them to contrast what our day-to-day lives are like with what people's day-to-day lives were like in the past. And so I’m proud that [this project will help] tell stories that can help bring that home for them.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.