March 23, 2015

VCU, UVA and Swedish researchers discover that childhood environment strongly influences the development of cognitive ability

Share this story

Young adults who were raised in educated households develop higher cognitive ability than those who were brought up in less ideal environments, according to a new study conducted by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of Virginia and Lund University in Sweden. While the study does not refute previous findings that DNA impacts intelligence, it does prove that environmental influences play a significant role in cognitive ability as measured in early adulthood.

The study compared the cognitive ability – as measured by IQ – of 436 Swedish male siblings in which one member was reared by biological parents and the other by adoptive parents. The IQ of the adopted males, which was measured at ages 18-20, was 4.4 points higher than their nonadopted siblings.

The findings will be published online in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on March 23.

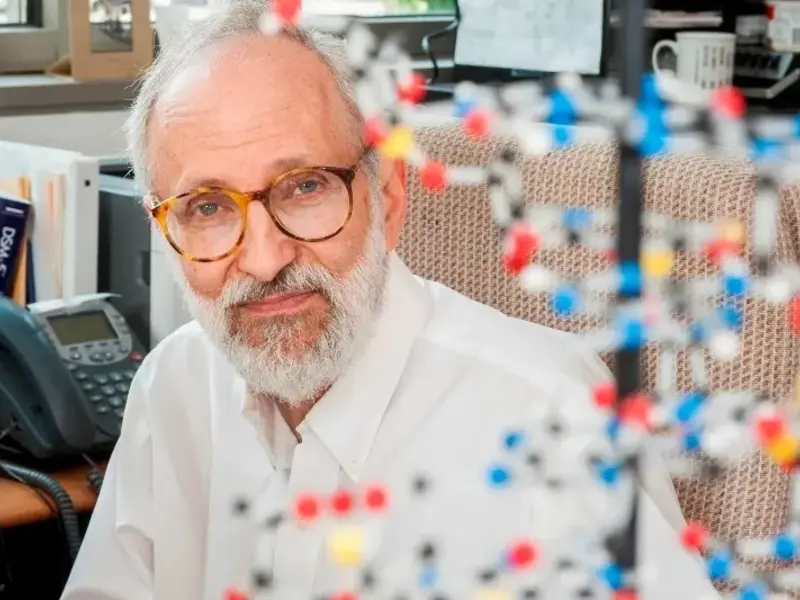

“In Sweden, as in most Western countries, there is a substantial excess of individuals who wish to adopt compared to adoptive children available,” said joint first author Kenneth S. Kendler, M.D., professor of psychiatry and human and molecular genetics in the Department of Psychiatry, VCU School of Medicine. “Therefore, adoption agencies see it as their goal of selecting relatively ideal environments within which to place adoptive children.”

The adoptive parents tended to be more educated and in better socioeconomic circumstances than the biological parents. In the study, parental education level was rated on a five-point scale and each additional unit of rearing parental education was associated with 1.71 more units of IQ. In the rare circumstances when the biological parents were more educated than the adoptive parents, the cognitive ability of the adopted away offspring was lower than the one who was reared by the genetic parents.

Adoption into a more educated household is the most permanent kind of environmental change, and it has the most lasting effects.

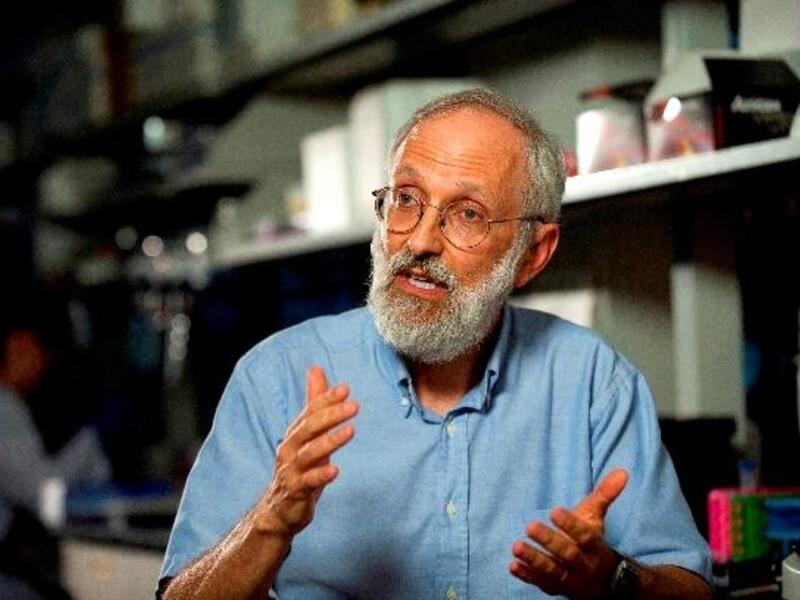

“Many studies of environmental effects on cognitive ability are based on special programs like Head Start that children are placed in for a limited amount of time,” said joint-first author Eric Turkheimer, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia. “These programs often have positive results while the program is in place, but they fade quickly when it is over. Adoption into a more educated household is the most permanent kind of environmental change, and it has the most lasting effects.”

Previous studies have found that educated parents are more likely to talk at the dinner table, take their children to museums and read stories to their children at night. “We’re not denying that cognitive ability has important genetic components, but it is a naïve idea to say that it is only genes,” Kendler said. “This is strong evidence that educated parents do something with their kid that makes them smarter and this is not a result of genetic factors.”

Turkheimer authored a landmark study in 2003 demonstrating that the effect of genes on IQ depends on socioeconomic status. The most recent study further affirms that finding.

“Differences among people in their cognitive ability are influenced by both their genes and environments, but genetic effects have often been easier to demonstrate because identical twins are essentially clones and have highly similar IQs,” Turkheimer said. “Environmental effects have to be inferred, as in the rare event when pairs of siblings are raised by different parents in different socioeconomic circumstances. The Swedish population data allowed us to find that homes led by better educated parents produce real gains in the cognitive abilities of the children they raise.”

The PNAS study is titled “The Family Environment and the Malleability of Cognitive Ability: A Swedish National Home and Adopted Co-Sibling Control Study.”

In addition to Kendler and Turkheimer, contributors to the study included Lund University researchers Henrik Ohlsson, Ph.D.; Jan Sundquist, M.D., Ph.D.; and Kristina Sundquist, M.D., Ph.D. Sundquist and Sundquist also have affiliations with the Stanford Prevention Research Center at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.