Oct. 14, 2020

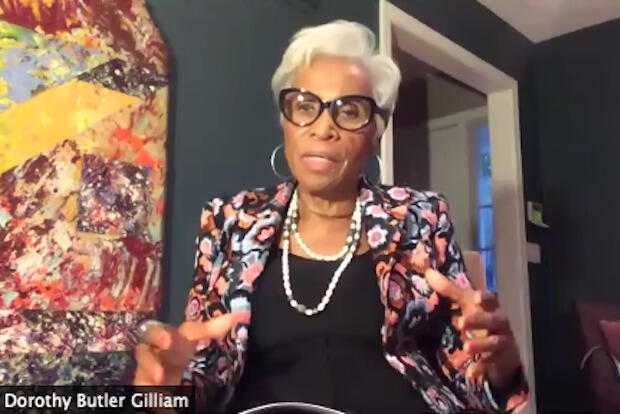

Washington Post trailblazer Dorothy Butler Gilliam on her career and the future of journalism

Share this story

When Dorothy Butler Gilliam was hired as the first Black woman reporter at The Washington Post in 1961, she was driven by the words of Martin Luther King Jr., when he said “Go and make a difference.”

It was far from easy.

“Taxi cabs wouldn’t pick me up when I was trying to get a cab so I could write my story and get back and make my deadline. It was very frustrating. But I had to do it and I had to make it work,” she said. “Sometimes when I went into white neighborhoods, it was an invitation to be abused. One time, [while visiting a home to do an interview] a doorman saw me and he said ‘You can’t come in the front door. The maid’s entrance is around the back.’ I was dressed nicely. I was very professional. But he just couldn’t believe that I was a reporter for The Washington Post.”

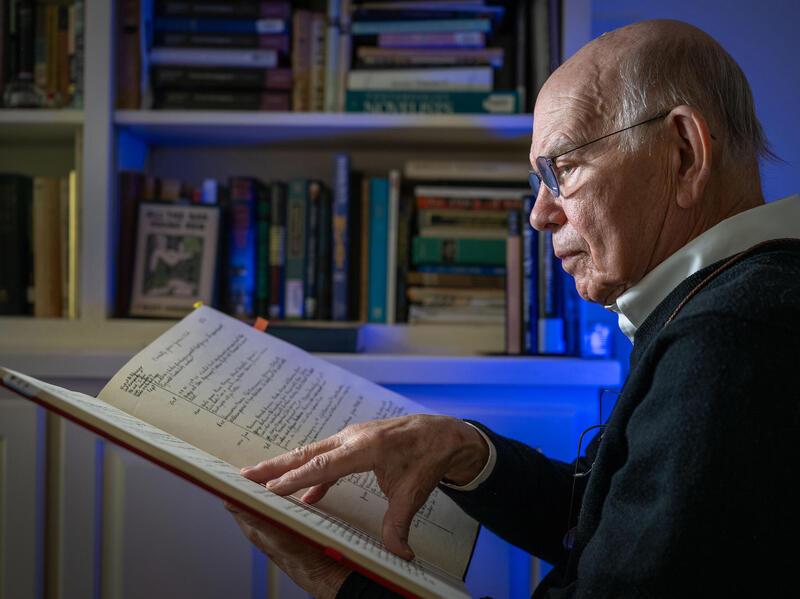

Gilliam discussed her trailblazing career Tuesday in a virtual event hosted by the Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture in the College of Humanities and Sciences at Virginia Commonwealth University and co-hosted by the Virginia Pro Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists and the BND Institute of Media and Culture.

Gilliam, a former president of the National Association of Black Journalists and author of the 2019 memoir “Trailblazer: A Pioneering Journalist’s Fight to Make the Media Look More Like America,” spoke as part of an ongoing speaker series hosted by the Robertson School. The event was moderated by Diane Walker, an anchor at NBC 12.

Gilliam’s career at the Post spanned a half century, and included time as a reporter, editor, columnist and director of the newspaper’s Young Journalist Development Program. She also has been a TV reporter in Washington, D.C., and a senior research scientist at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs, where she founded a program encouraging young people to pursue careers in journalism.

She also has a close relationship with VCU. She served as a Dabney visiting professor in 2000 and was a commencement speaker for the Robertson School when it was called the School of Mass Communications.

‘A front-row seat’

Gilliam’s journalism career began in the Black press. At 17, she worked as a secretary at the Louisville Defender and got her first opportunity to cover assignments when the paper’s society editor was out sick.

“It was a surprise to me that journalism opened doors to just so many new experiences,” she said. “I found that there was a small Black middle class in Louisville that I didn’t know about. These were the doctors, the lawyers, actually the editor of the newspaper. They lived in a certain section of town. My dad was a minister and we lived in the working class section of town. One of the great things about journalism and one of the reasons I’ve been so happy as a journalist is that it opens the door to new worlds. And it gives you experiences that you wouldn’t expect to have. It’s a front row seat to history.”

She attended Lincoln University in Missouri and after graduation was hired at the Tri-State Defender, a Black newspaper in Memphis, Tennessee. At that paper, she covered the integration of Little Rock Central High School, which was marked by violence, including the beating of her editor, Alex Wilson, by a racist white mob.

“I was back in the office where he left me covering what was going on in Memphis,” she said. “I looked up on the television screen, a little black-and-white television set in the office, and I saw the news that my boss was beaten by this mob. So I knew that I had to get to Little Rock. So I ended up going to Little Rock, Arkansas, with a photographer and really having the opportunity to cover this violent integration of Little Rock.”

Gilliam later worked at Jet Magazine and studied journalism at Columbia University. The Washington Post’s city editor would routinely visit to interview graduates, she said, and he advised her to get daily newspaper experience and then to come back and talk to the Post about working there. However, the Post’s interest was sparked when they later learned that Gilliam was going to Africa as part of a program called Operation Crossroads Africa that sent Black and white students to African countries to conduct service projects.

“When I told them I was going to Africa, that just seemed to interest them. They said, ‘Well, would you send us something you’ve written?’ And I did,” she said. “And when I came back, I was hired as the first African American woman reporter.”

Slights, determination, and James Meredith

As a trailblazer, Gilliam knew there was far more on her shoulders than others in the newsroom.

“I felt I was really showing people a different image of African Americans,” she said. “That was another job that I had, in addition to being a reporter and writing the story. It was also a time to help show the larger public — very often a very prejudiced public — that we, African Americans, were able and willing to do what it takes to really be a part of this nation.”

She experienced slights on a regular basis, she said. Colleagues would be reasonably civil at work and then pretend they didn’t know her elsewhere.

“I knew that if I failed, if I said, ‘This is crazy, I quit,’ then it would have been much more difficult for the next Black woman,” she said.

She added that the first Black man reporter at the Post, Simeon Booker, who was hired in 1952, only worked at the paper for about a year-and-a-half.

“He said, ‘I was getting neurotic. People thought I was sick because I trying to cover stories in a city where even the dog cemetery was segregated,’” she said. “He said it was just too much. So I didn’t want to fail. So I persevered. That is not easy but it is something that we, as African Americans, have to do.”

Looking back on her early years at the Post, Gilliam said the assignment that had the most impact on her was the integration of the University of Mississippi in 1962.

“Mississippi was like a place apart. It was a lynching state. It was a state where Black life was cheap. It was a place where the university was like this bastion of white supremacy,” she said. “And it was very, very difficult to [watch as] this lone man, one person, had the courage to integrate the University of Mississippi. His names was James Meredith. He had been in the Army. And he said he really came back to fight white supremacy.”

That assignment, she said, drove home how different her experience was from other reporters covering the story.

“The white people who were part of the team, they could stay at the Sand and Sea Motel and sit in the lobby and have lunch or dinner and talk about the story and trade ideas, as reporters do,” she said. “But I knew they would not rent me a room.”

Gilliam ended up staying in a spare room above a Black funeral home. “I slept with the dead. I did what I had to do,” she said. “Certainly nobody bothered me.”

At the time, Gilliam was one of just a handful of Black reporters at white newspapers across the country.

“You could probably have gotten all of us into a very small room,” she said. “It was important to make a difference, to show that we could succeed, that we could do the job.”

[The] doorman saw me and he said ‘You can’t come in the front door. The maid’s entrance is around the back.’ I was dressed nicely. I was very professional. But he just couldn’t believe that I was a reporter for The Washington Post.

‘We’ve got to make a difference’

Gilliam and other trailblazing Black journalists advocated for more newsroom diversity, but always encountered white editors saying they couldn’t find qualified applicants.

“We knew — the few Black journalists who were there — we knew that was not true,” she said. “We had to just jump into action and start training programs.”

Gilliam co-founded what became the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, which today continues to provide training to journalists of color.

“That was our response,” she said. “When we saw a problem that needed solving, we just jumped into action. We said, ‘We’ve got to make a difference.’”

Today, she said, newsrooms continue to need more diversity, as well as more inclusion and acceptance.

“The problems that I faced many years ago were different but there still are many, many issues that need to be resolved,” she said. “It’s important that we keep up the fight, keep up the struggle against those who don’t want us to have inclusion, those who don’t want us to be a part of society.”

“I really want this nation to change dramatically. It’s been 400 years of Black people pushing and taking two steps forward, and then being pushed three or four steps backward,” she said. “We’ve given so much to this country, we’ve sacrificed so much, we’ve served in places where we weren’t wanted but were needed. It is time for a change. It is time for the media to dismantle its systemic racism. It’s time.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.