June 3, 2015

Deconstructing the Confederate flag

Share this story

The Confederate flag — or more accurately, the battle flag of the Confederacy, which is the rectangular version most of us are familiar with — symbolizes many things. For some, it may celebrate their Southernness. For others, it may represent the Civil War and its ties to the legacies of race, slavery and economics.

For artist Sonya Clark, the flag’s most intriguing aspect is how polarizing it is.

“There’s no neutrality in this symbol,” said Clark, chair of the Department of Craft/Material Studies in the Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts. “People don’t say ‘whatever’ about the battle flag of the Confederacy. It’s not a neutral symbol. And because it’s not a neutral symbol, there are several access points to it. Some of those are contentious; a lot of them are. But I’m interested in how the symbol serves people differently.”

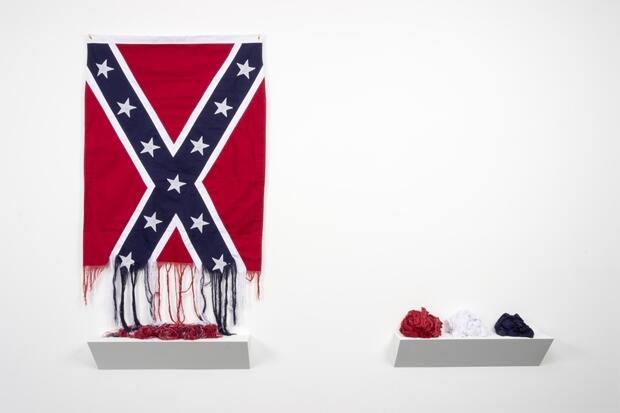

Clark takes an intimate look at that symbol in her latest work, “Deconstructing the Confederate flag,” debuting at New York’s Mixed Greens gallery this month as part of the “New Dominion” exhibition. She’ll kick off opening night on June 11 with a performance in which she will invite members of the audience -- including influential people in the civil rights arena and the arts community -- to take turns unraveling the flag with her thread by thread.

“New Dominion,” curated by Lauren J. Ross, curator of the Institute for Contemporary Art at VCU, presents a selection of eight artists living and working in Richmond, with a subtle nod to the city’s history and present. The exhibition presents works that touch on tensions between the past and the future, independence and loyalty, individuality and community. Seven of the artists, including Clark, have connections to the VCU School of the Arts:

· Susie Ganch, associate professor of crafts, fashioned tapestry-like wall hangings from discarded plastic coffee cup lids gathered from local coffee shops. These works not only find new life for a material generally regarded as disposable, but they also carry traces of Richmond’s literal DNA.

· John Freyer, assistant professor of photography, presents a work from his ongoing series “Free Ice Water,” in which he guides conversation between participants over Mason jars filled with water, drawing on the cultures of both relational aesthetics and substance abuse recovery.

· Hope Ginsburg, associate professor of art foundation, presents works from an ongoing series, “Breathing on Land,” in which she and other participants practice meditative breathing using scuba gear on dry land.

· Recent MFA alumna Noa Glazer combines materials and techniques that she conceives of as “Old World” and “New World” in her work. In “New Dominion,” she presents sand-casted salt forms embedded within synthetic foam.

· Arnold Joseph Kemp, chair of the Department of Painting and Printmaking, offers a sculpture that is simultaneously blessed and cursed, along with hand-painted photocopies that give touches of individuality to anonymous mask-like forms.

· Painting and printmaking professor Richard Roth’s paintings are grounded in modernism, yet rebel against its dogmatic tendencies by playing against doctrines of flatness.

· Clark’s second piece in the show, “Rooted and Uprooted,” focuses on the legacy of people of African descent in the Western Hemisphere. It addresses identity prior to and after slavery. As a first-generation American, Clark is intrigued by ‘Americanness’ and the ways in which we define it.

Rounding up the exhibition, Richmonder Ben Durham combines his own memories with Internet research on residents of his hometown to inform handmade paper works that are simultaneous portraits of individuals and their environments.

“Many of the works embrace a sense of reinvention, self-determination, ownership and agency,” Ross said. “Many contain a dose of something specific to Richmond. I loosely based the exhibition's theme on some thoughts about Richmond's history.”

As the capital of the Confederacy, Richmond’s history is intertwined with the Civil War. It’s fitting then that Clark started “Deconstructing” on the 150th anniversary of the war’s end.

“April 9 of 2015, we started unraveling the Confederate flag in the studio,” she said. “And the point of doing that was to have sort of a parallel to what’s happening in this contemporary time that has its legacy in slavery, its legacy in the Confederacy and the legacy in the history — the complicated history — of the U.S. … I just wanted to address that history but address it in the present context.”

The performance is not an aggressive act, Clark says. But set against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement, necessitated by recent events in places such as Ferguson and Baltimore, she hopes it will inspire interesting dialogue.

“The performance of it is almost a meditative kind of ‘what does it mean to undo the symbol?’” Clark said. “What does it mean to then use the raw elements that came together to make this symbol? To take them apart and potentially make something new again out of that?

“When you look statistically at what has happened in this century and the history and the legacy of people of African descent have been treated in this culture, of course anger is a natural emotion. With this piece, I’m really trying to think about … anger is justified, and then what? Because anger is simply an emotion. But I’m much more interested in what happens next. So how do we move forward and how far forward have we moved in 150 years?”

Just as undoing the harm of decades of social injustice is difficult, so is the physical act of unraveling the flag.

“It’s not an easy task,” Clark said. “This is the thing. It’s not an easy thing to undo. Thread by thread. It’s a little frustrating.”

This is not Clark’s first work involving the Confederate battle flag. In 2010 when then-Gov. Bob McDonnell designated April as Confederate History Month, she created “Black Hair Flag” in response.

“I didn’t have a problem with him doing that because of course Richmond is the seat of the Confederacy,” she said. “My issue, what I would take him to task for, is that he didn’t actually make any reference to the legacy or contributions that people of African-American descent have [made].

“What is he celebrating exactly, you know? Is he celebrating part of the history, the whole story of the history? And it seemed like in his conversation and in that proclamation, he was only celebrating part of the history. And so that led to the first Confederate flag piece that I made, “Black Hair Flag,” in which I inserted the presence of African-American people to finish or to complete part of the story that I felt like he was only sharing a slice of.”

For Clark, the Confederate flag is a symbol of the South and the Confederacy that has absorbed much history, dialogue and sensibility about Southern identity and race politics.

“I had to use a symbol that I could squeeze some stuff out of,” she said. “It’s absorbed all this dialogue around me and I want to … put my ear to the cloth and find out what it’s whispering.”

Feature image at top: From Sonya Clark's "Unravelling" and "Unravelled"

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday. VCU students, faculty and staff automatically receive the newsletter.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.