<br>Photos by Thomas Kojcsich, University Marketing.

Nov. 9, 2017

President’s Forum brings VCU together for critical conversations on monuments, political divide

Share this story

Along with the rest of the country, Richmond and Virginia are wrestling with difficult issues that have no easy solutions. On Tuesday, Virginia Commonwealth University convened a forum of faculty, students, staff, alumni and community members to discuss how to navigate these challenging problems, including how to govern in an era of deep partisan divides, and how cities like Richmond should approach their Confederate monuments.

“Our university has proven — and I want it to continue to prove — that we can work to engage in difficult conversations with civility, respect, deep thought and to be as informed as possibly can be,” said VCU President Michael Rao, Ph.D.

“This is a perfect environment for us to be good listeners, to learn from each other and to expand our views,” he said. “We do what's difficult and we do what's difficult well. And we do not turn our heads away from problems that really are the most vexing for people to have to deal with. We address them head on.”

The 2017 President’s Forum, “Engaging in Critical Conversations,” was held Tuesday afternoon in the Larrick Student Center on the MCV Campus, providing an opportunity for the VCU community to consider effective ways to take part in deep and informed dialogue on important issues facing Richmond, Virginia and local communities.

The event featured two panel discussions, one focused on finding a path forward through political discourse marked by discord and antagonism, and the other focused on Richmond’s history and future, with a particular emphasis on the city’s Confederate monuments. Following each panel, the audience broke into small groups to continue the discussion and to seek to generate more ideas, questions and solutions.

Is common ground possible?

The first panel featured two members of the General Assembly — Sen. Rosalyn R. "Roz" Dance, a Democrat from Petersburg, and Del. Peter Farrell, a Republican from Henrico County — in a discussion moderated by John Accordino, Ph.D., dean of the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs.

Why is it, Accordino asked, that it seems to have become so difficult for those with opposition views to find common ground in politics?

Farrell, who is retiring from his seat, said that he formed a number of friendships with his Democratic colleagues during his time in the House of Delegates, and that it is important to develop relationships and trust with others before tackling issues of disagreement.

“If Roz called me evil every day, I’d have no reason to work with Roz Dance. What’s the point? She doesn’t care what I have to say in that scenario,” he said. “But because I trust her and I respect her, it allows me to begin to have a conversation. That, to me, is one of the biggest things that’s changed. Now, you can read it on social media. ‘Oh, that's not true.’ ‘I don't trust that.’ There's no conversation anymore at all.

“Both sides are equally as guilty,” he added. “That’s where you've got to start. Stop thinking that your side is superior or better. Both are awful at this. They’re both ruining dialogue in the United States.”

Dance emphasized the importance of respect and listening to all sides.

“You’ve got to listen. You’ve got hear. You can’t just listen to one side. One side tells you [a piece of legislation] would be devastating. OK, let’s hear what the other side says. ‘The other side says it’s devastating, you tell me why it’s not. What do you have?’” she said. “There have been those cases when the best outcome happens when you bring them together.”

Dance also said lawmakers must keep a sense of modesty throughout the legislative process, and to remember that their job is to work together to help all Virginians.

“In the General Assembly, when a bill gets filed, that’s just the beginning. Because then you find problems. You come back the next year, and you amend it and you amend it until you get it right. But don’t think you get it right the first time,” she said. “You have to be patient, you’ve got to listen. You can’t get arrogant and think, ‘If I don't win this, I'll look bad or my numbers will look bad, I didn’t get a bill passed.’ You don’t want to get a dumb bill passed that’s going to hurt people just to say that you’ve got a record of getting bills passed.”

Members of the General Assembly, Farrell said, tend to get along fairly well, especially when compared to the animosity and partisanship in Congress. But the media, he said, tends to focus on the small areas of disagreement rather than the hundreds of bills that pass each year with huge bipartisan majorities.

“A lot of the times, when we get along, it’s just not very sexy [in reporters’ eyes],” he said. “For instance, I had to spend two years reforming a worker’s comp system with the views of doctors, workers, lawyers, employers. Got them all to agree. It took two years. It passed 100 to nothing. But nobody knows about it because it’s not very sexy. We do a lot of good work together.”

Wrestling with the past

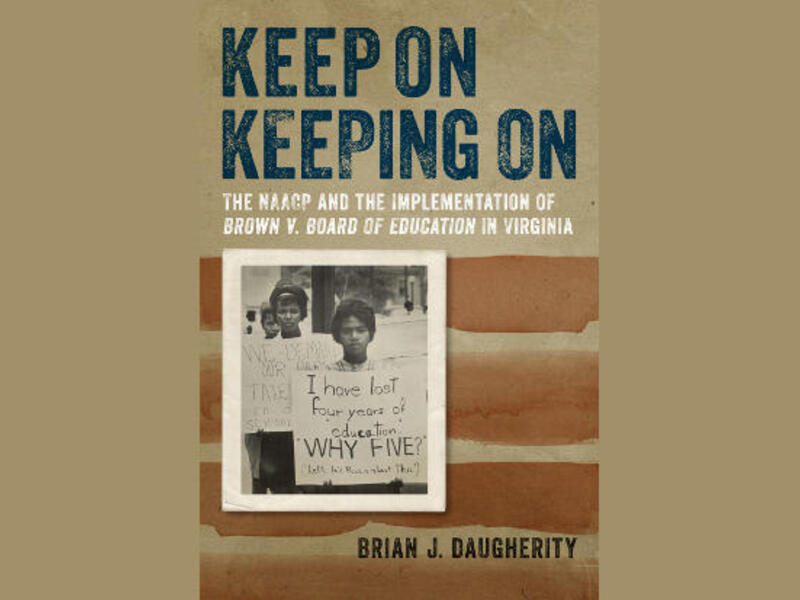

The second panel, moderated by Brian Daugherity, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of History in the College of Humanities and Sciences, focused on how communities such as Richmond are struggling with their histories linked to slavery and oppression and wrestling with public art and monuments. It featured Gabriel Reich, Ph.D., associate professor in the VCU School of Education; Melanie L. Buffington, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Art Education in the School of the Arts; and Christy Coleman, CEO of the American Civil War Museum.

“Many communities, including our own, are struggling with the ways in which public art represents and commemorates periods in American history,” Daugherity said. “As communities enter these conversations, what are key approaches and factors that we might consider in shaping our discussions and decision making?”

Buffington, whose current research focuses on public art, specifically the monuments of Richmond and how they reflect historical memories, said it is essential for the process moving forward to be as inclusive and deliberative as possible.

“It’s really important that we create a transparent process and allow time for many voices to be present in the process. It’s not going to be quick or easy. It took 20 years for the Robert E. Lee statue to get built,” she said. “Public art doesn't happen quickly. Commemoration usually doesn’t happen quickly.”

It’s important to recognize the voices that have been silenced in the past, and to make sure that we're listening to them now.

“It’s important to recognize the voices that have been silenced in the past, and to make sure that we're listening to them now,” she added. “And we also have to acknowledge that the silencing was intentional and that it was usually intended to enforce the power of white people over others. We need to recognize the harm that is done with some of the misrepresentations of the past. Especially when these misrepresentations are built into our community. In the case of Monument Avenue, it acts as a major thoroughfare in our city.”

Reich — whose current research focuses on the collective memories of the Civil War and Emancipation, and how those memories are affected by cultural tools, such as state history standards, examinations, public monuments, family stories and the practice of teaching — said a key question cities must ask themselves is, “What is the purpose of public art and monuments, and what do they convey?”

“That art represents us as a community whether we like the art or not and whether we like what it represents or not,” he said. “Communities change over time. Values change over time. So often public art becomes anachronistic. We think we’re very righteous now. But our descendants are going to look back at us and be shocked at some of the things that we say and do and believe.”

“[This] art was built to last. This art was put up to represent these ideals of ‘Lost Cause’ and they didn’t put it up in papier-mâché. It’s in stone. It’s in brass. It’s really durable materials and it’s still there,” he said. “We changed around it.”

Richmond’s Confederate monuments, Reich said, were built to serve as a teaching tool. The question is, he said, what are the statues teaching today?

“Look at the speeches that were made on the day of the unveiling of [the Robert E. Lee monument],” he said. “They talk about it as, ‘This is going to teach future generations. It was going to create continuity in this idea. The veterans were getting older at that point. They wanted to be sure that the younger generations would revere the heroes of the Confederacy in the same way that their parents and grandparents did.”

When Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney convened the Monument Avenue Commission to solicit public input and make recommendations about the Confederate monuments, Coleman and the American Civil War Museum decided to post online all the records, minutes and notes related to the monuments found in its Museum of the Confederacy collection.

“It’s there. We have it. We don’t have to guess what they were thinking. We have the minutes and the notes from these organizations,” she said.

Museums across the country, she said, are grappling with their role in the debate over Confederate monuments.

“All of us have also gotten that phone call, ‘If we take them down, will you take them?’ Because communities feel a level of absolution — ‘If we take them down and put them in a museum, then we’re all good.’” she said. “The problem is most of us do not have the resources to take art and monument and statuary of that scale and care for them to the standard. If you knew how much communities actually spent to keep the grass cut, keep the lights on, polish them up, all that kind of stuff, it would shock you. Museums simply don’t have that capacity.”

Richmond has an opportunity, Coleman said, to tell a wider story about the city and its public art and monuments.

“We do have so many amazing works of art and public history sculpture on the landscape,” she said. “Rather than being so obsessed with Monument Avenue — and, quite frankly, as a city, we marketed that to the world that that’s all we were for 50 years — but our landscape began to change as early as 1973 when the Bojangles statue was put up. So, today, we have an extraordinary wealth [of monuments and public art] that can tell about the life and the struggles of this city and its evolving scale in ways that no other city can.”

Subscribe for free to the VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Monday and Thursday during the academic year.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.