Nov. 25, 2013

Researcher strives to help middle school children with behavior issues succeed

Share this story

Succeeding in school can be challenging for any child, but the journey may be especially difficult for youngsters with attention and behavior problems.

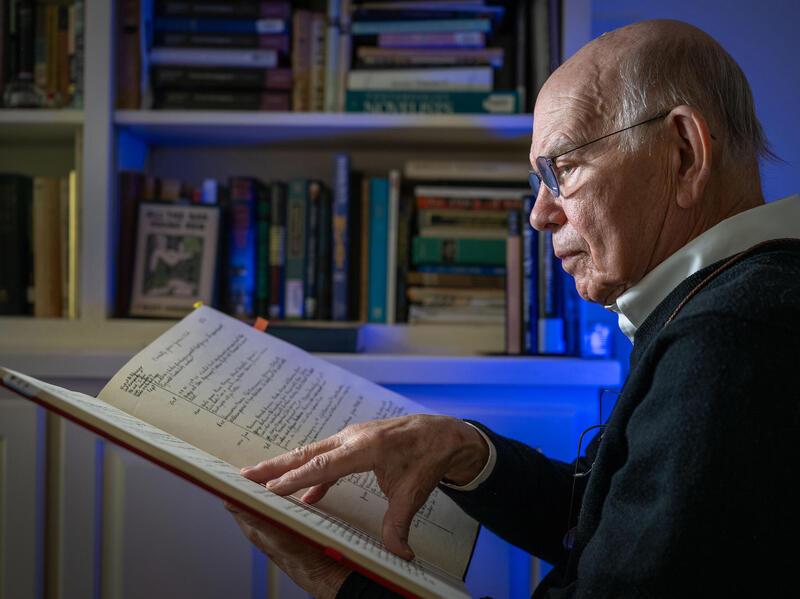

Joshua Langberg, Ph.D., assistant professor of clinical psychology in the Virginia Commonwealth University College of Humanities and Sciences, is hoping to make a difference for those children.

Langberg has spent the better part of the past 10 years working with schools across the country to develop interventions to help middle school students with conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) succeed in school.

For the next four years, Langberg and co-investigator Albert D. Farrell, Ph.D., professor of psychology at VCU, will be leading a $2.4 million grant from the Institute of Education Sciences to compare two different school-based interventions and determine which one may offer the most effective approach. The Institute of Education Sciences is the research arm of the United States Department of Education.

In 2008, prior to coming to VCU, Langberg developed the The HOPS Manual – Homework, Organization, and Planning Skills, an intervention for middle school students with ADHD that is implemented by school psychologists and/or counselors. From 2009 to 2012, Langberg worked with a number of school districts to determine an acceptable model for teaching these skills to students in schools. This was transferred into the manual, which outlines a step-by-step, session-by-session approach to be implemented in the school setting. This will be one of the interventions evaluated in his new study.

While HOPS was designed as a one-on-one approach, once Langberg met with school psychologists and counselors, they indicated that they saw themselves also using HOPS in smaller groups or as class-wide interventions. One school decided that they would instruct all students to use the HOPS system for organizing their school materials. So Langberg went back and revised the manual so it could be used in multiple ways and provides flexibility.

Working directly with schools to develop the intervention resulted in a program that is effective and feasible to implement – directly impacting the lives of students, families and teachers.

As co-founder of VCU’s Center for ADHD Research, Education and Service, which provides much-needed evidence-based ADHD services to the Richmond area, Langberg is also involved with training clinical and counseling psychology graduate students at VCU to provide evidence-based interventions for children, adolescents and families with attention and behavior problems.

Below Langberg provides insight into his work, where he hopes his field is headed and his passion for being a mentor.

How is the translational nature and impact of your research on children and schools relevant?

Langberg: I focus on developing interventions that can be implemented directly in school settings. This ensures that all children have access to care. I also focus on developing interventions that are really feasible for schools to use. Many times, that’s not the case – what we develop in research is really not usable in school and community settings. So I try to develop interventions for these youth that the school can really take and apply.

Many children with attention and behavior problems struggle with the skills needed to learn and succeed academically, such as organization, time management and planning skills. These skills are what all children and adolescents need to know in order to get homework done and to study for tests effectively and in a timely manner. These skills continue to be very important into adulthood and are necessary to be successful in college and in work settings.

Children with ADHD have particular difficulty with these skills. They may have the capacity to be A-B students, they are procrastinating, losing their homework, and as a result, they may receive C’s and D’s in their classes. Most of the interventions I have developed focus on helping children with ADHD in middle school do better academically. The main reason to focus on this age range is that middle school students with attention and behavioral issues often have a hard time with the transition to middle school. The context changes considerably – think about going from elementary school, where there is one teacher who really provides a lot of support and monitoring, to middle school, where students now have at least four teachers who each assign different homework and cannot provide the level of support and monitoring that was offered in elementary school. Children often struggle with this transition and so most of my interventions focus on supporting kids academically during and after that transition.

We really focus on teaching students how to organize their materials, plan ahead for the completion of tests and projects, record homework accurately and in sufficient detail, and to manage their time effectively and efficiently. Importantly, we also show families and schools how to use these interventions so they can help reinforce and monitor students using the skills.

The family and school piece are important. There are really no interventions for youth with attention and behavioral difficulties that work when delivered to children alone. We teach the child the skill, but what’s really important is teaching parents and school personnel how to monitor and encourage youth over time so they maintain the use of these skills.

Where do you see the future of your research field headed?

Langberg: I hope research will focus on developing feasible, easy-to-use interventions, even if that means that we have smaller effects and we have to continue to intervene over time.

I hope we will move away from testing interventions that take “the kitchen sink approach” and that target every behavior the child is having difficulty with at the same time. We’ve been doing that for a number of years and you can generate great effects, but the problem is that these interventions are costly and often require lots of staff time, effort and training to implement. I hope to see the field moving toward interventions that can really be disseminated. The goal is supposed to be that we develop not just something that works, but that can also be used widely.

Lastly, I hope the field moves toward a more chronic approach to treatment. Most research now is short-term. We want to see what we can cram into eight weeks and then cross our fingers and hope improvements last the rest of their lives. Frankly, that doesn’t work. So I think we should move toward smaller doses of intervention delivered continuously over longer periods of time. Maybe this will help with it being more feasible.

As a research mentor, what do you want your students to walk away with?

Langberg: Being a mentor is honestly the most enjoyable part of my job. I view training up-and-coming clinicians and researchers as one of the primary responsibilities of my job.

In my case, during my post-doctoral and graduate training, I had some excellent and invested mentors who took the time to teach me how to be effective as a researcher and a clinician. Working with those mentors throughout graduate school and their support is really what got me started on this path and why I have been successful with a research and training career.

I currently mentor students at all levels – from undergraduates to post-doctoral scholars. I expect my students to work very hard, but most leave with the skills both academically and interpersonally that they need to be successful and are able to make informed career choices.

What advice do you have for students looking to enter the research field?

Langberg: The environment is pretty competitive these days and students have to get started early. I think it’s especially important for undergraduates and early graduate students to understand this. Mentors don’t come to you – students need to be assertive and seek out mentors. It may take many tries to connect with the right one, but the search needs to start early. Coursework only counts for half of the game, if not less. Students need to be proactive and work with people who are doing research. That is going to set them on the right path.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.