June 30, 2016

Seipel retires after four magical decades in the School of the Arts

Share this story

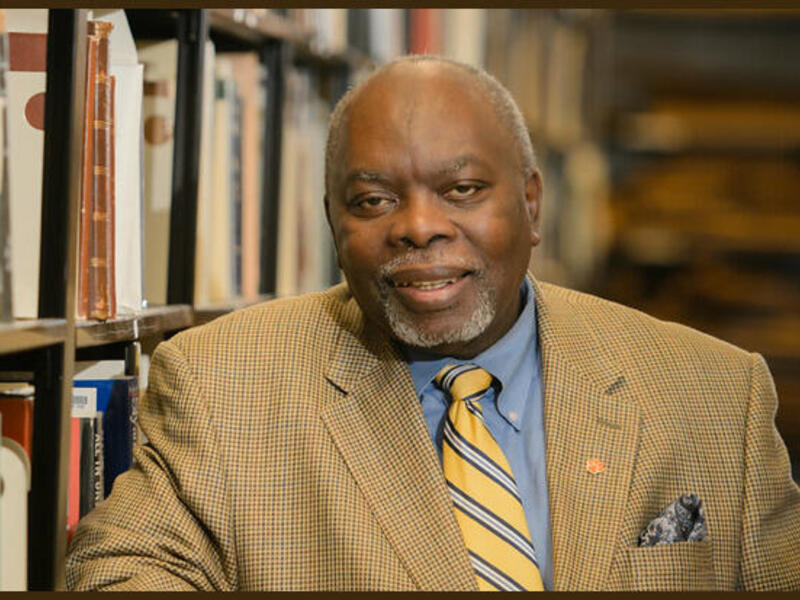

Joseph H. Seipel came to Virginia Commonwealth University in 1974 with a one-year contract to teach in the Department of Sculpture. More than 40 years later, he is retiring as dean of the School of the Arts. In that time, he says, the School of the Arts has become part of his DNA. Even more so, Seipel has become part of the school’s DNA.

“I’m leaving with absolutely great memories of a spectacular 42-year career and I couldn’t have asked for a better life,” said Seipel, who retires today. “The colleagues and friends that I have are lifelong and what an experience this has been. It’s been great.”

Under Seipel’s leadership, the school rose from No. 4 to No. 2 overall among arts programs in the U.S. News & World Report list of America’s Best Graduate Schools and maintained its No. 1 position as the top public program.

Even when this was Richmond Professional Institute, this was a hell of a good art school and VCU has had a good art school all along.

“Even when this was Richmond Professional Institute, this was a hell of a good art school and VCU has had a good art school all along,” Seipel said. “If I did anything to assist in that, it’s because those rankings are actually based on reputation and I have a big mouth. I never had a question about our quality, ever. … It’s just been making sure people know about it. And then we worked really hard on recruiting the best graduate students we could.”

Seipel followed a storied road to the arts and VCU. As a student at the University of Wisconsin, he started in art education but had second thoughts after taking a three-hour lecture course that he was sure he would fail. “I was horrible,” he said. “I would leave halfway through all the time and I actually never bought the textbook. … I took the test cold.

“I was not a very good high school student but I was a pretty good college student. I remember going home and letting my mother know that I was going to fail a course in college and she was pretty upset about that.” In the end, the class did turn him away from art education, but not because he failed the class.

“I got a B. And I was so offended that I could get a B in art education for so little work and being such a nitwit that I dropped out,” he said. “Then I went into ceramics.” While Seipel was one of the better students, his ceramics teacher Bruce Breckenridge took offense when he learned Seipel wanted to work with famed ceramicist Peter Voulkos at the University of California, Berkeley.

“One night, about 2 in the morning, I was sitting on the floor making some molds or something when Bruce walked in. My teacher walked in and stepped on all my molds,” Seipel said. “He’s walking drunk and he steps on all my molds and laughed at me and said, ‘Berkeley huh?’ And then roared off just laughing and went into his office. He was my mentor — I mean, I was devastated.”

Breckenridge threw Seipel out of his class, saying he could not come back until he came up with some new ideas. Seipel left all his classes for about two weeks, during which time he drew and tried to develop ideas that personally connected with him. Two weeks later, Seipel returned with an inches-thick stack of drawings and Breckenridge decided the drawings demonstrated Seipel should be in sculpture instead of ceramics.

“And that’s how I got into sculpture,” Seipel said.

Seipel left the University of Wisconsin after his first year of graduate school and moved to Boulder, Colorado, where he worked for the Boulder Valley School District as a media production specialist. He then moved to Baltimore and earned his MFA at the Rinehart School of Sculpture at the Maryland Institute. Afterward, he tended bar at Bertha’s in Baltimore, where he became friends with filmmaker John Waters and his crew who frequently hung out there. At that point, he applied to VCU for a teaching position.

Seipel’s 1974 interview with Harold North, then chair of the VCU Department of Sculpture, started at a picnic table behind 914 W. Franklin St. and lasted all day. Seipel ended up staying for a party where he realized the university community was “a spectacular community of like-minded artists. … The next day they called me back and asked what it would take to come to VCU. I said, ‘I’d sure like to make $9,000 a year,’ and they offered me $11,500 and I had the world by the ass.”

Decades later, Myron Helfgott, retired sculpture professor, still remembered Seipel’s application.

“When Joe applied for the job in 1974, there was a number of other applicants,” Helfgott said in a 2011 discussion. “But one thing that endeared Joe to us was that he sent a photographic self-portrait in bib overalls signed Joseph ‘Joe’ Seipel. ‘We want that guy!’” (Incidentally, in the same discussion, Seipel mentioned that he traded one of those publicity shots to Allen Ginsberg for a lock of hair.)

At the time, the sculpture department was on the second floor of a carriage house behind 914 W. Franklin St. and its studios were in virtually every garage down the alleyway between Franklin and Grace streets. Seipel gave his first class lectures in the basement of the president’s office at 910 W. Franklin St.

<slideshow id=140 align=center width=450>

In 1985, Seipel became chair of the department under Murry DePillars, Ph.D., then VCUarts dean. Richard Toscan, Ph.D., would succeed DePillars as dean more than a decade later.

“For many years Joe was a key part of my team as we built the national reputation of the School of the Arts from 25th when I arrived in 1996 to one of the top four programs in the nation and the No. 1 public university art and design school in the U.S.,” Toscan said.

“As head of our Department of Sculpture in those early days, he was one of the first to realize that telling the story of how well our graduates were doing professionally was a key to building national stature. Joe always loved a good party with friends and colleagues and cleverly used these get-togethers at national conferences to send a stealthy message about how great we really were. The beer may have been free, but everyone left — even if they didn’t realize it at the moment — knowing more about the School of the Arts and the powerhouse we were becoming in the field.”

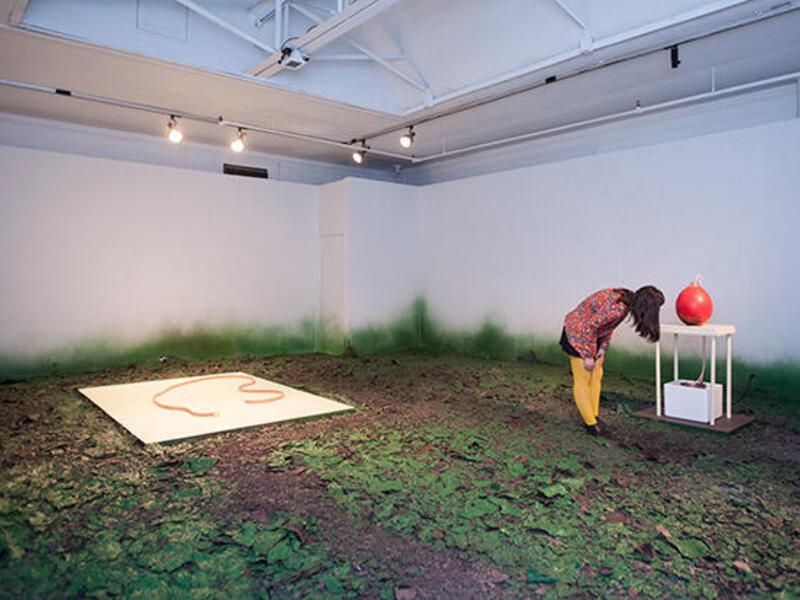

One of Seipel’s initiatives that garnered national attention for the sculpture department was changing its curriculum to include more technical opportunities for students. For that, the International Sculpture Center presented him with the 2001 Outstanding Sculpture Educator award.

“That was a total shock,” he said. “I was surprised. That was a very nice honor and that all happened because of the kind of faculty that we had in the sculpture department. … There was a commitment beyond just the teaching – there was a commitment to the community. If people needed to come in on a Saturday, they came in on a Saturday. If they needed to spend 60 hours a week, they’d spend 60. If we didn’t have money and we might have to go to a conference, four of us would go in a room we’d pull a mattress off the bed and sleep on the box springs and the mattress.

“It was very different than it is now. But we developed a kind of a close-knit community that got attention throughout the country for, for all sorts of reasons, not the least of which was they were making really good work.”

Also In 2001, Seipel became senior associate dean of the VCU School of the Arts. During his tenure, he had been offered other dean jobs that he turned down. But when the Savannah College of Art and Design came knocking in 2009, he had become a little restless and thought it would be a particularly interesting challenge.

“It was actually a great move for me, because it put me into an art school that was an art school. It wasn’t an art school in a comprehensive research university,” Seipel said. “Plus it was a private school and I was a vice president there so I got a chance from a pretty lofty position to see how the operation ran.”

But the Savannah job also made him realize how much he missed being in a big research university. And two years later, when Toscan announced his retirement, Seipel was at the top of the list of possible replacements.

“I missed my friends in pharmacology,” he said. “I missed my friends in business and engineering, down at the medical school, in humanities and science. ... Coming back here it was like being in heaven. I loved it and I also find a lot of people with kind of like minds who wanted to do research across disciplines, something that was very much on my mind — what is the worth of an art school in a research university? How do you take advantage of all of those opportunities? And that’s something that I’ve been trying to do.”

Since becoming dean, Seipel has been a passionate advocate of cross-disciplinary partnerships across the university, particularly with arts and the health sciences. For Seipel, art goes beyond entertainment or culture. It changes the way medical care is given, influences how doctors see things and sparks new ideas in the medical field.

Joe’s leadership has made VCU a creative campus.

“Joe’s leadership has made VCU a creative campus,” said VCU President Michael Rao, Ph.D. “From the support he galvanized to raise funds for the Institute for Contemporary Art to the dynamic, cross-disciplinary connections and innovative programs he has initiated across campus, Joe has been instrumental in positioning the School of the Arts as a global, forward-thinking institution.”

Dinkus Deane, director of operations at the School of the Arts, has known Seipel since the 1980s when the former was an undergraduate student in painting and printmaking. Later, as chair of the sculpture department, Seipel mentored Deane as a graduate student in the program. When Seipel became dean, he asked Deane to return.

“Joe gave me a call about five years ago and asked if I had time to help manage a little project they had going on at the Pollak Building,” Deane said. “It was the dean’s suite renovation. I had been working on movies and for my own construction company for years and I thought a change of pace would be nice. When the job was finished, he offered me a full-time position. Greatest job I've ever had. Joe is the best boss I have ever had. I worked for myself for 10 years so I'm well aware of what a rotten boss is like!

“Joe's legacy … is his dedication to the students and the arts, and we will see that dedication for decades to come in the buildings that we call Depot and ICA. I would also mention kindness. He is the kindest of people, and even when things get tough, he always has a smile on his face.”

Seipel calls it unusual for an art school to be so respected in an urban research university. But he describes VCU as the “university of yes” because nobody ever says no. “If you want to do some research with the medical school or business or engineering or humanities and sciences everybody is willing, and that’s not usual in big universities, I assure you,” he said. “We’re very lucky to have the colleagues that we do across this campus.”

Seipel has two studios — a 2,000-square-foot studio and a 900-square-foot studio — one of which still has unfinished work that he started some 20 years ago. “So the first thing I’ve got to do is I’ve got to finish that work, find some catharsis with that work and hopefully have an exhibition sometime in the not-too-distant future. And then see what happens,” he said.

Seipel says it will take some time to get his studio legs back. “You can always go out and you can make something, but to have a sustained practice is really what you need if you’re going to be making work that responds the way you want it to.

“And then, I might read a book — who knows? I might just read a book or once in a while just get in the car and go for a drive just for the hell of it.”

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.