June 28, 2017

To end the opioid epidemic, VCU health sciences faculty are changing the way pain management is taught

Share this story

Opioids: An American health crisis

Overdose deaths in the United States involving prescription opioids have quadrupled since 1999, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ninety-one Americans die daily from an opioid overdose and more than 1,000 are treated daily in emergency departments for not using prescription opioids as directed. In 2016, Gov. Terry McAuliffe and Virginia Health Commissioner Marissa Levine declared the opioid addiction crisis a public health emergency in Virginia.

At VCU and VCU Health, efforts are underway to combat this public health crisis — through addiction treatment, pain management, health care policy, education and research. This multipart series provides a snapshot of those efforts.

F

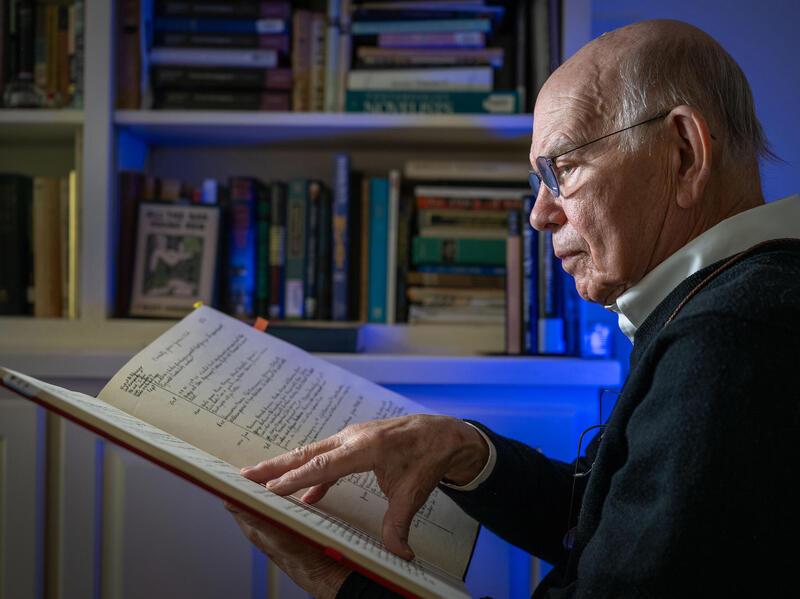

or two years following his youngest son’s death, Omar Abubaker, D.M.D., Ph.D., could not take the elevator to his parking space at Virginia Commonwealth University’s MCV Campus. To get there, he would have to walk past the campus bookstore where he spent his final moments with Adam before hugging goodbye at the corner of 12th and Leigh streets and hearing his son say “I love you” for the last time. Adam Abubaker overdosed on a fatal mixture of heroin and benzodiazepine early the next morning. He died on Oct. 2, 2014. He was 21.

“There is no way to truly describe the feeling of losing a child,” Abubaker said. “It is as if a part of me died, but continues to constantly ache.”

The National Institutes of Health estimates about 80 percent of heroin users started with prescription pain medication. Adam fit the narrative. In high school, he had surgery for a minor shoulder injury sustained during football practice. The surgeon prescribed 90 Vicodin pills after the procedure. Abubaker believes that first physician-enabled exposure to narcotics led to his son’s heroin addiction.

“He didn’t get hooked at the time,” Abubaker said. “But eventually he kept coming back.”

Since Adam’s death, Abubaker has committed himself to learning about the disease that took his son’s life. He has studied the biological basis of addiction and the dangers associated with overprescribing opioids. He teaches what he learned to anyone who will listen. At VCU, the School of Dentistry professor and department chair instructs courses to dentistry students on safe opioid prescribing and to nursing students on how to work with patients who struggle with addiction.

Abubaker is not alone in his mission to educate students about opioids. Last fall, VCU School of Medicine became the first allopathic medical school in Virginia to adopt the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s new opioid prescription guidelines into its curriculum. Earlier this year, physicians and educators from VCU’s Schools of Medicine and Dentistry collaborated on a web-based continuing medical education course that instructs practicing physicians, nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants on safe opioid prescribing practices.

Across the university and health system, VCU faculty members are changing the way pain management is taught and working together to quell the nationwide opioid addiction crisis.

“A big part of the opioid epidemic is due to physician practice,” said F. Gerard Moeller, M.D., professor of medicine at VCU and director of the VCU Institute for Drug and Alcohol Studies. “Now, we have to do two things: We have to reduce people’s exposure to opioids and, for those who are already addicted, we have to treat them. If you just cut off the oxycodone, the patient is going to switch to heroin.”

‘A problem that starts in health care’

The vast majority of American doctors overprescribe pain medication. Health care providers wrote 259 million prescriptions for painkillers in 2012, according to the CDC — enough for nearly every American to have their own legal bottle of opioids.

“The correlation between opioid-related deaths and the increase in opioid prescriptions is striking,” said Alan Dow, M.D., assistant vice president of interprofessional education and collaborative care and professor of medicine and health administration at VCU.

The prescription increase started in the 1990s, when national pain medicine organizations began issuing guidelines that included the recommendation of using opioids to manage chronic pain. Pain specialists at the time argued the nation faced an epidemic of untreated pain, with the American Pain Society advocating for the recognition of pain as the “fifth vital sign.” In 2001, the Joint Commission, a national health care facility standard-setting and accrediting body, implemented pain standards for hospital accreditation, requiring health care providers and hospitals to ensure their patients received appropriate pain treatment. In some cases, doctors were found liable for not meeting patient expectations.

At the same time, an extensive marketing campaign was in effect for using OxyContin in the treatment of non-malignant pain. OxyContin sales representatives visited physicians across the country, leaving them gifts, free patient samples and invitations to all-expenses-paid symposia. The pharmaceutical company that makes OxyContin augmented the marketing campaign by downplaying the drug’s addictive potential and targeting primary care physicians, who continue to prescribe the majority of opioid pain relievers according to the CDC.

“I was part of the problem,” Moeller said. In the ‘90s as a medical professor in Texas, Moeller recalls teaching students there were no data to show that chronic pain patients were at risk for opioid addictions.

“Unfortunately, what we thought then was not true,” he said. “I think that is a large part of why the opioid epidemic has taken such a toll.”

From 1996 to 2000, annual global OxyContin sales increased from $48 million to almost $1.1 billion, according to a 2009 article in the American Journal of Public Health. Other opioids such as morphine and codeine also experienced an unprecedented rise in production and sales at that time.

Overdose death rates increased with the increased opioid sales. The overdose death rate in 2008 was nearly four times the 1999 rate; sales of prescription pain relievers in 2010 were four times those in 1999; and the substance use disorder treatment admission rate in 2009 was six times the 1999 rate, according to a 2011 CDC report.

In 2013, drug overdoses surpassed car crashes as the leading cause of unnatural deaths in the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The numbers continue to rise, with more than 90 Americans dying every day from opioid overdoses, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“People start by abusing prescription medications and then move on to harder stuff,” Dow said. “This is a problem that starts in health care.”

Pursuing sobriety

Abubaker speaks of his son tearfully, and in the present tense.

“He is a good kid,” he says. “I had no suspicion he was in danger until I found out about the heroin. It was too late by then.”

The Tuesday after Thanksgiving in 2013, Adam, along with his brother and sister, visited Abubaker at his Church Hill home. Gathered in the living room, the siblings told their father about their brother’s addiction as Adam sat sorrowfully beside them. Adam’s brother had discovered his heroin paraphernalia a few days earlier and, when confronted about it by his older brother, Adam confessed.

“I was shocked,” Abubaker said. “I thought maybe he used marijuana every now and then, but never heroin. It was naïve, but I didn’t realize people in our socioeconomic status used heroin. I thought, ‘What am I going to tell people?’”

It was naïve, but I didn’t realize people in our socioeconomic status used heroin.

Adam checked himself into a drug treatment center in Richmond’s Northside the next day and lived there drug-free from December 2013 until April 2014. On Mother’s Day 2014, soon after he had moved to a supervised sober home with other recovering addicts, Adam called his father screaming. His mother, from whom Abubaker separated when Adam was a child, had died suddenly in her sleep from a heart condition. The shock of his mother’s unexpected death tested Adam’s sobriety, but he was able to abstain from drugs with the support of his housemates, with whom he went daily to group therapy.

In August 2014, Adam moved into an Oregon Hill apartment and started taking emergency medical services classes at John Tyler Community College. He also started working full time as a sales representative for an automotive equipment engineering company in the city. A month later, on a Friday afternoon in September, Adam met with his counselor at VCU Medical Center’s Nelson Clinic and then joined his father for lunch at his office down the street.

“He sat there and I sat here,” Abubaker said, motioning to the yellow upholstery couch in his office in the Wood Memorial Building.

For two hours, father and son discussed Adam’s new job, his classes and the bright future that lay ahead. “The last thing I said to him? ‘One of these days we’ll celebrate your sobriety and go on vacation, just you and me,’” Abubaker said, his voice breaking. “Adam said, ‘Maybe one day, but for now, one day at a time, Dad.’” Looking back, Abubaker believes Adam could feel an impending relapse.

After lunch, Abubaker walked with his son to the campus bookstore to buy Adam a stethoscope and two books for class.

“We talked for another 10 minutes and then, right by the traffic light here, he said, ‘I love you, Dad. I’ll call you tomorrow.’”

Abubaker was instead awoken early Saturday by a call from a police officer.

“The officer said to me, ‘I just found your son pulseless and not breathing,’” Abubaker said.

Paramedics restored Adam’s pulse and transferred him to a local hospital. For five days Adam lived on a ventilator, but his brain activity had ceased. Every day, Abubaker arrived at the hospital in the morning and stayed until night hoping for a miracle, but he refused to see his son in the intensive care unit.

“I wanted our last memories to be happy,” Abubaker said. “I didn’t want to see him with the tubes.”

The other side of shame

The funeral home could fit 600 people; attendees flooded the sidewalk at Adam’s funeral.

“We made the decision when my son died that people needed to know he died of addiction,” Abubaker said. At the funeral, the family told the story of Adam’s struggle. “That was the beginning of facing the public, even though I was not completely over the shame,” Abubaker said.

Searching for something to ease the pain of his grief, Abubaker enrolled in the International Program in Addiction Studies, a partnership among three of the world’s top research universities in the field of addiction science: King’s College London, the University of Adelaide in Australia and VCU. In May 2016, he earned a graduate certificate in international addiction studies.

“I started learning things in that course that made me think, ‘I am a doctor and I didn’t know any of this,’” Abubaker said. “As I learned more, I committed myself to teach what I had learned.”

In the fall of 2016, Abubaker introduced to the dental school’s third-year students a lesson on forms of addiction and how to manage patients who have addictions. He also teaches an oral surgery course on post-operative pain management to second-year dental students and oral surgery residents, in which he incorporates information about pain medications and alternatives to narcotics. At the School of Nursing, he lectures on the opioid epidemic and addiction to psychiatric and mental health nurse practitioner students.

Abubaker’s efforts extend beyond the university. The VCU faculty member traverses the commonwealth talking to professional dental organizations about opioid addiction and risks of over prescription. He is often called to explain new statewide regulations on opioid prescription practice to professional dental organizations. This fall, he will teach a two-hour continuing education course on opioid prescribing to Virginia dentists at a statewide conference and will present on the topic at a national oral and maxillofacial surgery conference.

This isn’t just about science, it is about real people.

At every lecture, he talks about his son.

“I bring Adam up every time I teach about addiction because this isn’t just about science, it is about real people,” he said.

Abubaker teaches students informally during clinical rotations as well. He recalls a time when he was teaching students in the dental clinic about the extent patients who are addicted to pain medication will go to get the drugs.

“I told the students, if they suspect a patient might have issues with pain medication, they need to tell the patient they are worried about them and want to help,” he said.

The next day, one of his students emailed him: “She wrote, ‘You should be proud of me. I had a heroin addict as a patient today and I had the courage to talk to him like you said. He didn’t get upset. I took the tooth out and gave him ibuprofen and he left without asking for narcotic pain medications.’”

The student told Abubaker the conversation she had with him the previous day helped her identify the patient as an addict and guided her discussion with him about alternatives to narcotics.

“That gives me faith,” Abubaker said.

A university-wide approach

At the same time that Abubaker was introducing courses on safe opioid prescribing practices at the School of Dentistry, Moeller was amending the School of Medicine curriculum to align with new CDC pain management guidelines. The guidelines that were issued in March 2016 recommend significant restrictions on the use of opioids in chronic pain treatment. They advise physicians to try alternatives to opioids when possible and, if opioids must be prescribed, to start slow with low dosages.

In a lecture to second-year medical students, Moeller explains the reasoning behind the CDC recommendations, discusses non-narcotic alternatives to opioids and guides students on how to adjust patient expectations on chronic pain treatment.

In addition to the curriculum amendment, Moeller and his medical school colleagues instituted a practical unit in which students are presented with a robotically simulated patient who has overdosed on opioids. The students are provided with the patient’s medical history, which is that of someone who has been in chronic pain treatment with opioids. They are expected to revive the patient with the overdose-reversal drug naloxone.

“We added a more live example of what an overdose might look like,” Moeller said. “We want students to leave with the idea that chronic pain should be managed primarily with non-opioid medications, which has not been the way of thinking in recent history.”

Divergence from the trend

As of the start of 2017, Virginia requires physicians who are renewing their medical license to complete two hours of continuing medical education credits around safe opioid prescribing. Physicians are required to complete 60 hours of CME credits every two years.

In the spring, VCU introduced a web-based course through the university’s Center for Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Care that integrates the CDC’s 2016 opioid guidelines with the Virginia Board of Medicine opioid prescription guidelines issued in March. The course is intended to arm physicians with practical approaches to prescribing opioids more safely and to instruct physicians on how to provide better care for patients who use opioids.

The seven-module course instructs students on the extent and demographics of the opioid epidemic, the biological basis of opioid addiction, best practices for safe opioid prescribing and how to identify and refer patients with potential opioid use disorders to appropriate care. Short videos introduce big concepts and are followed by case studies and questions that help participants apply what they have learned and get a sense of how it integrates into their practice.

“If we prescribe opioids more safely, we can start to decrease those downstream problems of opioid overdoses and long-term opioid addiction,” Dow said. “This is a generally slowly evolving disease, and we have a chance as health care providers to intervene.”

Carrying his son’s torch

Nearly three years after his son’s death, Abubaker has gathered the courage to ride the elevator to his parking space, but he still cannot step foot inside the campus bookstore where he shared his last moments with Adam.

“My memories with Adam are in Richmond,” he said. “Even the pleasant memories are painful now. That is what hurts the most.”

The work he does on opioid addiction education is in addition to his responsibilities as a department chair, dentistry school faculty member and practicing surgeon, but he sees it as part of his grief process.

“In some ways, this is my therapy,” Abubaker said. “When you get into it, you almost get distracted from the pain.”

He views his commitment to opioid education as an extension of Adam’s generosity. His son, who spent much of his youth as a volunteer firefighter in Central Virginia, was altruistic even through his death, donating his organs to save four lives as his parting gift on Earth. “The time I now spend teaching about addiction and opioids is what Adam would have done had he lived a full life,” Abubaker said.

He hopes through his work, that less people will be prescribed unnecessarily lengthy opioid prescriptions and that fewer fathers will have to go through the pain of losing a child to addiction. He also wants to leave students with an understanding of addiction as a disease.

“Adam tried to teach me about addiction when he was alive,” Abubaker said. “I couldn’t be this way if it wasn’t for him. I will never get to see my son grow up, get married or have children of his own, and I will never see him realize his dreams, but I can tell his story. My work now is a continuation of what Adam started. In the end, this will be his legacy.”

Addiction resources

| The McShin Foundation 2300 Dumbarton Rd., Richmond, Va. 23228 (804) 249-1845 Recovering addicts and alcoholics |

Caritas (The Healing Place) 700 Dinwiddie Ave., Richmond, Va. 23224 (804) 358-0964 ext. 114 Addiction recovery resources for homeless men |

| FCCR Rehabilitation Center 4906 Radford Ave., Richmond, Va. 23230 (804) 354-1996 Specialized treatment options for alcohol abuse or substance abuse *Other locations in Midlothian and Fredericksburg |

Saara of Virginia, Inc. 2000 Mecklenburg St., Richmond, Va. 23225 (804) 762-4445 Alcohol and other drug addiction |

| Hanover County Community Services Board 12300 Washington Highway, Ashland, Va. 23005-7646 (804) 752-4200 (804) 752-4275 Alcohol and drug abuse |

Chesterfield Mental Health Services 6801 Lucy Corr Blvd., Chesterfield, Va. 23832 (804) 748-6356 Adult substance abuse services |

| Henrico Mental Health and Developmental Services 10299 Woodman Rd., Glen Allen, Va. 23060 (804) 727-8515 Treatment services for drug and alcohol abuse |

Richmond Behavioral Health Authority 107 S. 5th St., Richmond, Va. 23219 (804) 819-4000 Substance use and prevention services |

Subscribe for free to the VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Monday and Thursday during the academic year and every Thursday during the summer.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.