Aug. 25, 2016

VCU professor is helping America’s oldest tambourine ‘sing again’

Share this story

In 1994, Preservation Virginia’s Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists were excavating the original site of James Fort when they found a small copper alloy cymbal, also known as a “jingle,” that was once part of a tambourine that arrived in the colony prior to 1610 — making it the oldest known English tambourine in the United States.

Now, as part of an upcoming exhibit refresh at the Jamestown Settlement museum, the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation is seeking to recreate that tambourine, and has enlisted the help of a Virginia Commonwealth University professor to ensure the replica is as accurate as possible.

“This is bringing an object back to life,” said Bly Straube, Ph.D., former Jamestown Rediscovery senior curator who was instrumental in the effort to find the 1607 remains of James Fort, and who is consulting on the exhibit. “It was buried for 400 years. We did resurrect it, and put it in the museum — it’s in Jamestown Rediscovery’s archaeological museum, the Archaearium, on Jamestown Island.

“Now, we’re going to make it sing again.”

This is bringing an object back to life … we're going to make it sing again.

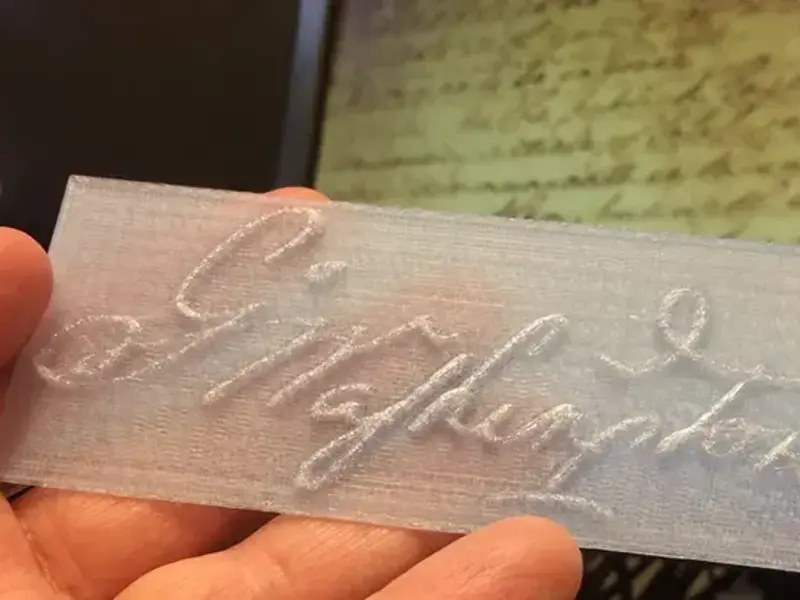

Last week, Bernard Means, Ph.D., an anthropology professor in VCU’s School of World Studies in the College of Humanities and Sciences, visited Jamestown Rediscovery’s lab to 3-D scan the jingle, allowing him to create a digital 3-D model for use in replicating the tambourine.

“I’ll take the 3-D model back to the Virtual Curation Laboratory at VCU where I will edit it. Once I get that done, I’ll make two reproductions in plastic that will be accurately modeled to the size and shape of the object, and then folks at the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation will be able to make replicas of the tambourine,” he said. “It’ll allow them to reproduce the sounds of the 17th century with an accurate reproduction of a tambourine from that era.”

As part of the project to reproduce the tambourine, the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation enlisted the help of John Paul Lindberg, a former principal percussionist and principal timpanist at the Virginia Symphony and an instructor of percussion at the College of William & Mary.

“I got an email from Dr. Straube, and she asked if I’d be interested in signing on,” he said. “She told me, ‘We have found a tambourine jingle, probably dating from 1608 to 1610, and we need to replicate a tambourine.’ I was like, how could I not sign on to this? It’s really cool.”

As a percussionist, Lindberg said the opportunity to help create a museum-quality reproduction of the earliest tambourine in America was too good to resist.

“The first time I came in here and held the jingle in my hands, I felt like I was going to cry. It was just … you never get to touch an instrument of that vintage. I mean, holy cow,” he said. “My interest in the whole thing is very simple. I want to see a reproduction of this tambourine in a museum, and I want it to be as perfect a reproduction as possible — that’s why we wanted to 3-D scan the thing. It was something that absolutely had to be done to make it a museum piece.”

With the 3-D model of the jingle in hand, the team plans to work with Norfolk Machine and Welding to recreate the jingles, and with Grover Pro Percussion in Boston to build it.

“I called a man by the name of Neil Grover of Grover Pro Percussion, which makes probably the best tambourines in the world,” Lindberg said. “I said, ‘Neil, you want to sign on to this? We need a tambourine built, but we need to do it from one jingle.’ So we looked at it, and thought it’s probably a 10-inch tambourine — it’s a small jingle — and we’re going for it.”

Straube, who was senior curator at Preservation Virginia’s Jamestown Rediscovery for 21 years, and who helped start the project in 1994, is working with the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation to refresh its 17th-century exhibition galleries. The tambourine, she said, will be featured as part of an installation on musical instruments played by three Jamestown-era cultures: the Angolans, the Powhatan and the English.

“For the Africans, it’s a gong. For the Powhatan, it’s a gourd rattle. And, because I knew about the tambourine [jingle], I suggested the tambourine for the English,” she said. “Part of our exhibit, I think, will be audio, so it is important for us to recreate the tambourine.”

Several other indications of musical instruments have been found at Jamestown, including two trumpet mouthpieces, several Jew’s harps, three whistles, a number of rumbler bells and the mouthpiece to a woodwind instrument, possibly a recorder.

“We don’t find too many musical instruments. We’ve only found a handful, but [they] show a whole other side of life of the fort that’s not really been documented,” Straube said.

Means, who has spent the summer 3-D scanning artifacts such as 2,000-year-old terracotta figurines in India, mastodon fossils in California and dog vertebrae dating to 400 A.D. in upstate New York, said the Jamestown tambourine is a particularly special project.

“It’s really interesting,” he said. “In archaeology, I’m used to picking up and touching things. One of the really nice things about this artifact is that not only will we be able to touch it, but we’ll be able to use it to actually hear the past.”

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.