May 21, 2015

VCU study finds students are eating fruits and veggies in school lunches, contradicting criticism

Share this story

Under new federal school lunch regulations championed by Michelle Obama, school cafeterias across the country must now offer more whole grains, vegetables, and fruits, and less fat and sodium. But the new guidelines also sparked widespread criticism that children hated the healthier lunches and were choosing to simply toss out the fruits and vegetables.

As it turns out, that is likely not the case. A forthcoming study led by Suzanne Mazzeo, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Psychology in the College of Humanities and Sciences at Virginia Commonwealth University, found that the majority of school children are choosing to eat the school lunches' fruits and vegetables.

"Most kids are eating the fruits and vegetables is the bottom line," said Mazzeo, a leading expert in healthy eating and exercise, particularly for children and families.

The study, which was conducted at two Title I elementary schools in Chesterfield County, is funded by a two-year $100,000 grant by the National Institutes of Health. The study's results are among the first empirical evidence to show that the overhaul of the National School Lunch Program is working and that school children are actually eating the healthier school lunches.

Mazzeo recently discussed her team's findings and offered a preview of the forthcoming study.

Now that you've wrapped up your research in the Chesterfield County elementary schools, what are your initial findings? What conclusions have you drawn?

We had two main questions. The first was: Are they eating their fruits and vegetables?

We focused on fruits and vegetables because those are probably the most important components of a school meal, particularly for these kids in Title I schools. They're lower-income kids, and most get free- or reduced-price lunch. [School lunches might provide] some of the only fruits and vegetables they have all day.

We focused on that because we know that fruits and vegetables are really important to obesity prevention and prevention of other chronic diseases like cancer. Whether the kids are overweight or not, it's important for them to eat fruits and vegetables. So we wanted to see if that was happening.

And, secondly, in one of the schools, we did a tasting intervention to see how that would affect the kids' consumption of fruits and vegetables as well.

We found that most kids were already eating their fruits and vegetables. They weren't throwing them out. Looking at both schools at baseline, almost 45 percent of the kids had nothing – no fruits or vegetables – left on their tray.

And then 20 percent of the kids had everything left on their tray – so 20 percent ate no fruits or vegetables. But as most parents know, some kids never stop talking enough to eat anything. And some kids might just be really picky eaters. There's a certain amount of kids who just don't eat much of anything, no matter what you serve them.

But, overall, more kids had nothing left than any other group. Most kids are eating the fruits and vegetables is the bottom line.

For the tasting intervention, we took little sample cups [of fruits and vegetables] and told them 'This will be on the menu in the next few weeks. Would you like to try it?' And then, if they tried it, they got a sticker. We assessed both schools right after that, and then we checked again six weeks later.

[After six weeks], it went down a little bit in both schools, probably as the novelty wore off because we started at the beginning of the school year. But we pretty much saw the same pattern – that the greatest number of kids had nothing left on their trays.

At the school where we did the tastings, those kids had even fewer fruits and vegetables left on their tray. So the tasting intervention, even though it was incredibly simple, worked.

That's kind of exciting because [this type of tasting intervention] is something that schools could actually do. It's not expensive, and it wasn't specially prepared food – it was food that was already on the menu, made by the county.

Were these findings a surprise?

This is what we hypothesized, so it wasn't really a surprise (although it is always nice when things work out like you hoped!) But we were excited by the results because there was so much talk last year about kids throwing away the fruits and vegetables. There were a lot of provocative media reports. And you can go on YouTube and see all these videos of kids making fun of the new lunch policies or saying how much they hate the new school lunches.

But there weren’t much data out there, and these are some of the first data that shows empirically that kids are eating the fruits and vegetables.

And these are the kids who are most at risk of obesity and all the chronic diseases related to not having enough fruits and vegetables, and they're also more likely to live in food deserts where they don't have as much access to fresh produce. So that's why we particularly wanted to focus on these schools. And because so many of them are on free- and reduced-price lunch, it's not as much of an option for them to bring their own lunch.

What did the data collection entail? How did that work?

That was a big learning process for us. We looked at some other studies, and [in those, researchers] stood at trash cans and observed what the students threw out. That's what we'd planned to do initially, but it turned out – especially with little kids – there's a huge line. We wanted to be as unobtrusive as possible and not bother the kids and not bother the staff.

So what we ended up doing was have … We had a little sheet that noted whether they had taken the fruit or vegetable for that meal and what it was, and stuck it under their tray. And then when they were done, we told them "Don't throw it away. We'll rate it and then throw it away for you."

We got more plates than we even thought we would because once we figured out the most efficient way to [collect the data], we were able to get almost every first through third grader.

What are implications of findings and how can they inform policymakers and schools?

I feel really hopeful about this study because when you talk to people about school lunches their first reaction is usually like, gross, the kids don't want to eat that and we just need Jamie Oliver in every school.

I'm a really practical person. We're not going to get chefs in every school. Yes, there are some programs doing that, but not every school is going to get a grant to have these fabulous meals made. We have to be realistic about what is possible within our current means.

...We were able to show that schools can easily do things to get kids to eat fruits and vegetables.

So I like that we were able to show that schools can easily do things to get kids to eat fruits and vegetables.

There are things we can do that are practical and realistic that we can do right now without waiting for some amazing cafeteria grant to come our way. It really was not expensive, and we showed that kids – the kids that we're most concerned about – will eat their fruits and vegetables.

What's the next step for your research?

Richmond recently started offering free meals to everyone in the inner city schools. Part of the same federal law that changed school lunches said that if you have at least 40 percent of your school is eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch, then the whole school can get free lunch without having to submit extra paperwork.

Chesterfield County decided not to [take part], even though they have schools that are eligible.

We want to do something similar to this study, but looking at how universal lunch impacts kids. Does it make them more likely to eat fruits and vegetables as part of that lunch? Do they pack a lunch and get a school lunch too?

We want to compare schools that did take advantage of this policy and those that didn't to see if there are differences in what the kids are eating.

There have been a few studies in the last couple years that have found that packed lunches are actually less healthy than the school lunches. Which makes sense if you think about it – I know when I pack my kids' lunches, it's hard every day to find a fruit and vegetable that they want to eat.

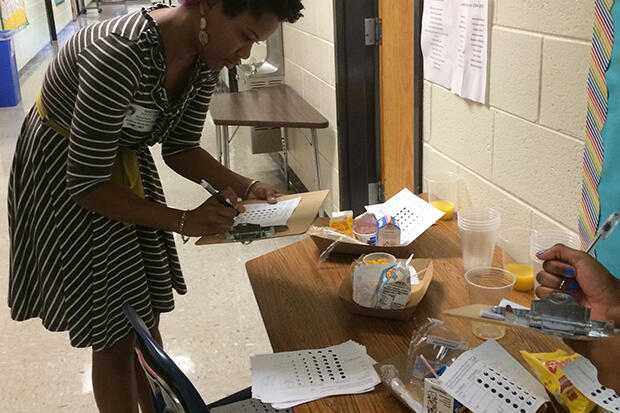

Feature image at top: Rachel Boutte, a counseling psychology graduate student at VCU, rates how much fruit and vegetables remain on students' plates in a Chesterfield County elementary school.

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday. VCU students, faculty and staff automatically receive the newsletter. To learn more about research taking place at VCU, subscribe to its research blog, Across the Spectrum at http://www.spectrum.vcu.edu/

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.