<br>Photos by Brian McNeill, University Public Affairs

April 7, 2017

VCU, UR students confront question: ‘What would a truthful representation of Richmond’s history look like?’

Share this story

Students from Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Richmond came together Tuesday with a panel of Richmond community activists and archivists to wrestle with the question: “What would a truthful representation of Richmond’s history look like?”

The idea is that the popular narrative of Richmond’s history too often fails to accurately convey the experience of the city’s black population and too often glosses over the ugly parts — Richmond’s slave trade, Jim Crow, the decades of segregation.

“Our goal was to get experts from the community to actively engage with students on this question, and to get VCU and UR students in dialogue,” said organizer Micol Hutchison, Ph.D., director of program development and student success for University College.

At Tuesday’s forum, there were students from a VCU Focused Inquiry course, in which they have been conducting informal ethnographies of the neighborhoods around VCU, while also learning about race relations and inequities in Richmond — such as the East Marshall Street Well Project — and politics in the city, today and over the past century.

There were also students from two University of Richmond classes: “Representing Civil Rights in Richmond,” taught by Laura Browder, Ph.D., the Tyler and Alice Haynes Professor of American Studies in the Department of English; and “Memory and Memorializing in the City of Richmond,” taught by Nicole Maurantonio, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Rhetoric & Communication Studies.

“Throughout the semester,” Browder said, “our students have wrestled with questions of justice and reparations: Why do we commemorate certain aspects of history, and choose to forget others? What does it mean for the Confederate cemetery to be funded with taxpayer money while the African-American cemetery remains overgrown and neglected? What does it mean for an important site in Richmond’s history as a center of slave trading to be paved over for a parking lot? What are the ways we can reach wider audiences with these hitherto untold stories, and open up new conversations about painful topics?”

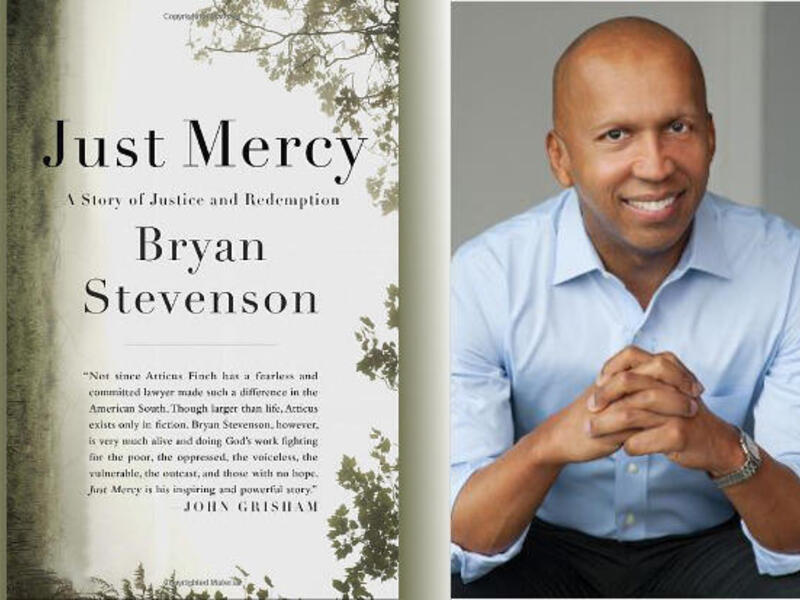

The event was part of a series of a year’s worth of events at VCU related to the university’s 2016–17 Common Book, “Just Mercy,” a 2014 memoir by Bryan Stevenson, a civil rights lawyer and professor, in which he tells the stories of his clients — often poor and often minorities — at the Equal Justice Initiative who were wrongfully convicted and otherwise mistreated by the criminal justice system.

Stevenson will speak at VCU on April 12, at 6 p.m. in the Siegel Center. His talk will be free and open to the public.

“Our Common Book events this year have all connected to the themes of ‘Just Mercy,’ but not always in obvious ways,” Hutchison said. “In our classroom discussions of ‘Just Mercy,’ we have explored the causes of mass incarceration, as well as the short- and long-term effects on the community. Within this, we have examined the unequal treatment that minorities and the poor receive in the criminal justice system and in society.”

“The question that then arises is, ‘Why? Why are these groups treated differently?’” she said. “One of the answers to this question is that underrepresented minorities and the poor are often treated and viewed as lower-class citizens in our society. This leads us to look at the city we live in and how it treats and has treated all of its citizens, and how it considers, represents and memorializes its past.”

For the UR students, Tuesday’s gathering at VCU was the culmination of a semester of field trips and class visits that explored “sites of memory” in Richmond, she said.

“Nicole’s and my students have been to the Tredegar Civil War museum and the United Daughters of the Confederacy,” she said. “We have walked Monument Avenue and have spent a morning working at the East End cemetery and have hosted a number of artists and archivists concerned with telling Richmond stories — especially stories that have for too long gone untold.”

The panel of community experts featured archivists Ray Bonis, a senior research associate at VCU Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives, which has a number of collections related to people and organizations who have traditionally been underrepresented, and Irina Rogova, project archivist at the Race & Racism at the University of Richmond Project, which aims to recover and interrogate the university’s history to create an equitable and inclusive environment for the community.

You cannot tell the story of the city by leaving out the story of nearly one-half of its people.

“You cannot tell the story of the city by leaving out the story of nearly one-half of its people,” Bonis said. “African-Americans, women and other groups — especially the working class, of both races — are often underrepresented in telling the story of this country, let alone Richmond.”

Rogova encouraged the students interested in telling a more accurate story of Richmond to “find people in the community who have had to keep their own histories because no one else is doing it for them.”

But, she added, it is important to forge meaningful connections with those community archivists. “Don’t just go in and grab their history and say ‘I’m going to put this in my archive and you’re never going to see it again,’” she said. “Make those connections, and make them accessible.”

The panel also featured community strategist Lille Estes; Christopher Rashad Green, who is on the family representative council for the East Marshall Street Well Project; Free Egunfemi, a historical activist and founder of Untold RVA; and Vaughn Whitney Garland, Ph.D., a sound artist and oral historian.

To achieve a more truthful representation of Richmond’s history, Green said, it must include the voices and stories of Richmond residents whose stories have been ignored.

“The question is how would I like to see Richmond? It’s very simple. We want the people of Richmond — the community — to tell the narrative. We have brilliant people in our community,” he said. “How I like to see Richmond, we need to take control of our destiny. You don’t know my journey, my history, but I’m going to bring that to the table.”

Egunfemi agreed, saying experts on the truthful history of Richmond can be found among the African-American community.

“The first thing we would do is look toward the nontraditional intellects in our community because obviously black people haven’t had equal access to education. So to think that the only people that can inform this dialog are people who come through a university is mistake No. 1,” she said. “When you are doing your work in the world, make sure you’re reaching out beyond just whoever shows up to the community conversation. Find the black community experts who have devoted their lives to preserving and promoting the narrative.”

Also on the panel were documentarians, journalists and educators Erin and Brian Palmer, who are currently working on “Make the Ground Talk,” a documentary on a historic black community that was uprooted during World War II to build a naval base. They talked about their work as volunteers cleaning up Richmond’s overgrown black cemeteries.

“When we think about what we would like the narrative of Richmond to look like, it’s one that acknowledges the context for a place like East End [Cemetery],” Erin Palmer said. “Face the evidence. These places did not become overgrown in a vacuum. They did not become illegal dumps in a vacuum. … So we talk a lot about the laws that were put into place post-Reconstruction that started to restrict the political and economic power of African-Americans just as they were emerging from the Civil War and Reconstruction, building institutions, building community, building churches, building fraternal organizations — all of which we see reflected at East End.”

Brian Palmer, who is also an adjunct faculty member with University College and is helping organize Common Book events, said that a truthful representation of Richmond needs to accept evidence such as the stories of Richmond’s black community that can be found in the Richmond Planet, an African-American newspaper founded by 13 Richmond slaves that was published from 1883 to 1938.

“What’s prevented us from accepting all that evidence?” he said, showing a newspaper story on the projector screen. “From 1889, this is the Richmond Dispatch, the narrative — which in some ways is still with us — is ‘Negro fiend lynched in Alexandria last night for the usual crime.’ So there’s a kind of continuity in the way that African-Americans have been represented. And if you remember Bryan Stevenson, he talks about narratives of racial difference. Meaning, there are stories we’ve inherited about particular people. So the story of black men is dangerous and guilty.”

Subscribe for free to the VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Monday and Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.