Dec. 1, 2020

How personal tragedy set this former VCU trainee on the path to become a urologic oncologist

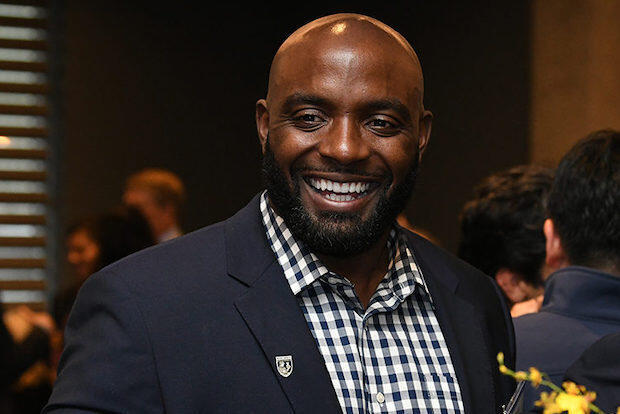

After his grandmother died of cancer, Randy Vince Jr. decided to pursue medicine to address the health care inequalities that exist for African Americans.

Share this story

Randy Vince Jr., M.D., was in his second year of medical school when his beloved grandmother died of kidney cancer. As he learned more about her last days, he realized she could have been a candidate for a potentially lifesaving surgery.

Her physician never even suggested the procedure.

Soon after, Vince made a decision that changed the trajectory of his career: to become a urologic oncologist that Black Americans like his grandmother needed.

“I decided I wanted to know how to perform the surgery she was not offered and be the best at doing it,” said Vince, who completed his urology residency at Virginia Commonwealth University’s MCV Campus in 2019. “I wanted to help families in similar situations. It’s been well-documented that people of color are not given the same standard treatments of care.”

I decided I wanted to know how to perform the surgery she was not offered and be the best at doing it. I wanted to help families in similar situations.

Vince points to studies such as one published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science in 2016 that examined beliefs associated with racial bias in pain management. The study provides evidence that false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and whites continue to shape the way medical students and physicians perceive and treat Black people, and that those beliefs are associated with racial disparities in pain assessment and treatment recommendations.

Now a urologic oncology fellow at the University of Michigan, Vince regularly speaks with communities of color about the basics of cancer and its treatments. “I’ll give talks to groups of Black men so they have a working knowledge of prostate cancer and can advocate for themselves,” Vince said.

In July, as COVID-19 and social unrest thrust health inequities into the national spotlight, Vince contributed to the Journal of the American Medical Association’s “A Piece of My Mind” series with an article titled, “Eradicating Racial Injustice in Medicine — If Not Now, When?”

In the article, he calls on physicians and the medical community to become leaders in addressing the pervasive inequalities that exist in the health outcomes for African Americans and proposes a series of steps to do so successfully.

He also describes growing up in West Baltimore, where as a kid he wondered why his family had to deal with basic struggles like putting food on the table and keeping the heat on, and details his experience as a Black man in medicine.

“During medical school, I was one of five African Americans in a class of 120 students,” Vince writes. “I listened with great discomfort and despair to countless lectures describing the health conditions that disproportionately harm African Americans. In none of these lectures, however, did any instructor explain or acknowledge what I had observed for many years — that access to care is a primary factor behind these disturbing statistics.”

At Michigan, his research includes using genomic platforms to enhance the diagnostic and prognostic data for clinicians and patients. “Additionally, I aim to use genomic panels to highlight the impact of systemic racism, not racial biology, on disparities in cancer outcomes.”

Vince returned to VCU — virtually — on Nov. 5 to deliver a presentation, “The Impact of Systemic Racism in Medicine: A Data-driven Assessment,” at the Department of Surgery’s Grand Rounds.

“It gives me a lot of pride that Randy [Vince] came out of our program,” said Lance Hampton, M.D., chair of the Division of Urology. “With all that is happening now in our country, it was clear to me that what he described in JAMA was a conversation we needed to be having. He lays it out in a very impactful way.”

Hampton, the Barbara and William B. Thalhimer Jr. Professor of Urology, notes that urology lags behind other specialties in terms of racial diversity. Only 2% of urologists are Black; 4% are Latino. To build a program and a field that more closely reflects society, the Division of Urology has created a new Diversity Scholars Program to attract top minority medical students to complete an away rotation on the MCV Campus.

“It will give us the ability to see the best students from around the country and hopefully they end up staying here for residency,” Hampton said. “Even if they don’t, it’s a good way to improve diversity in urology overall by providing experience in academic medicine and access to urologists who can write letters of recommendation. We have an opportunity to be the leaders in expanding racial diversity in our field.”

Vince also has made it a goal to expose more students to urology through his mentorship of pre-med and medical students, and is currently working with 20 mentees. He knows the importance of having just one person who believes in you and instills confidence in your choices.

“If I hadn’t had that one professor who told me I was smart enough to be a physician, I probably would have tucked my tail between my legs,” Vince said. “I didn’t know anything about becoming a doctor. It was really hard and took a long time. But I got into medical school, I got top scores on my board exams and matched into an extremely competitive specialty. Think how many kids have the potential to do this and more.”

This story originally was published by the VCU School of Medicine under the headline ‘I wanted to be the best.’

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.