Sept. 27, 2022

VCU professor's documentary explores the first psychiatric facility for African Americans and the history of scientific racism

Share this story

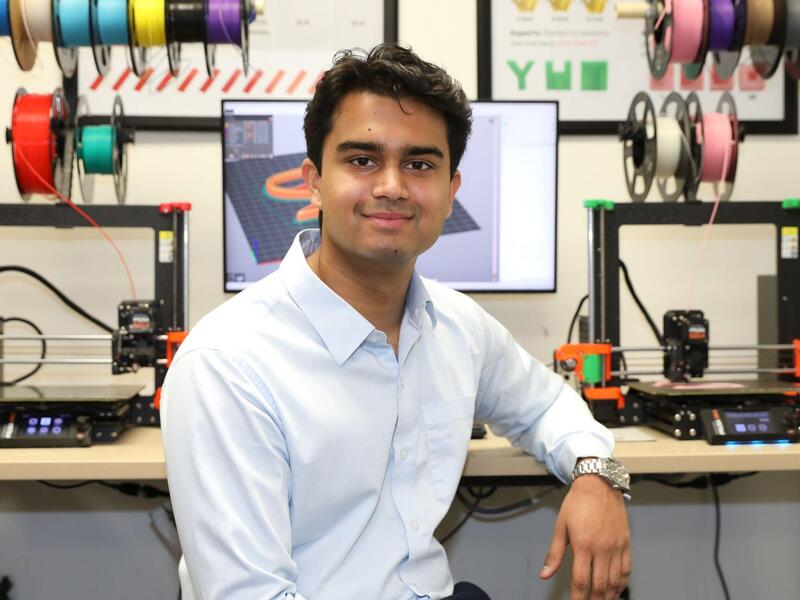

Shawn Utsey, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Psychology at the College of Humanities and Sciences, has been preparing for the moment he could explore the history of the first psychiatric facility for African Americans in the U.S. since he first came to Virginia Commonwealth University in 2004. Now, the Central State Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane, more recently known as Central State Hospital, is the subject of Utsey’s latest documentary.

Utsey’s film, “The Central Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane,” a Burn Baby Burn production, premiered at the Afrikana Film Festival in Richmond on Sept. 17.

This is the fourth feature-length documentary for Utsey, who studies how race-related stress impacts the physical, psychological and social well-being of African Americans. He has also written and directed the 2010 film “Meet Me in the Bottom: The Struggle to Reclaim Richmond’s African Burial Ground,” the 2011 film “Until the Well Runs Dry: Medicine and the Exploitation of Black Bodies” and the 2018 film “Toward a Black Psychology: Origin and Evolution of a Discipline.” His latest project on Central State similarly takes viewers through the history of a site at the intersection of race and health.

“I’m hoping that people will be inspired by the story of this hospital that began in the aftermath of slavery that had one purpose — to warehouse the newly freed African Americans who were suffering from mental illness and many who weren’t — and how it evolved over the years into a place that the community began to connect with and take pride in and that members of the community who worked there thought of as a family,” said Utsey, the film’s writer and director.

In 1869, the Central State Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane in Petersburg opened, becoming the first psychiatric facility in the U.S. to exclusively treat African American patients. Many white physicians of the time were among the same ones who had invented psychiatric disorders afflicting Black patients, including drapetomania, a “disease” that caused enslaved Africans to flee captivity. The conditions at Central State when it opened were akin to warehouses, “not necessarily for health reasons but for reasons of control, of punishment,” Utsey said.

As time went on, the facility continued to be understaffed and underfunded compared to facilities for white patients, such as Eastern State Hospital, Utsey said. This exacerbated the already significant disparities in mental health and other health care facilities that Black patients experienced during segregation.

“In the ’50s and ‘60s, the number of Black Ph.D.’s in psychology and the number of psychiatrists of color were limited. And so, at the hospital, although it was entirely Black patients and all of the service staff were Black, all the doctors and the administration were white,” Utsey said. “So it was kind of a colonialized medicine model, if you will, and that power differential and the distance from the decision-makers and the community added kind of fuel to the fire to make the gap even wider.”

In terms of aligning with the cutting edge of psychiatric medicine, “they were kind of behind the times,” Utsey said of the hospital due to lack of resources prior to integration. Electric shock therapy and lobotomies were commonly performed. When integration came in the 1960s, Utsey said, conditions were not much better.

“The staff report that, at Central State Hospital, they sent their best clients, the highest-functioning clients, to Eastern State Hospital, and Eastern State sent their lowest-functioning white clients to Central State. That magnified the struggles they already had,” Utsey said. “Integration wasn’t kind to Central State and the mental health treatment of African-Americans in Virginia. We can still see the lingering effects of a poorly planned integration for redistribution of resources to benefit Central State.”

For hundreds of years in the U.S., psychiatric conditions have been diagnosed differently by race, and resources have been distributed unevenly in terms of funding and training for mental health care. These are effects Utsey still sees today.

“I think what’s important in terms of the documentary is how it deals with the history of scientific racism and how scientific racism has created these notions of ‘insanity’ (the term in that era) that are different for Black folks than for white folks,” Utsey said. “For example, there’s this false notion that Black people who are insane are more likely to express that as mania or anxiety and that white folks are more likely to be depressed. Those kinds of ideas are still borne out in the differential diagnoses that Black patients received in these hospitals.

“Black patients are more likely to receive a more severe diagnostic description, and when they are diagnosed with anxiety, they’re more likely to be overmedicated, as opposed to depression. I still think we have a lot we can learn about the remnants or the residuals of scientific racism and how that’s painted a narrative of racial differences in mental health.”

In the process of making this documentary, Utsey said what surprised him most was the stories of the Black employees he interviewed from the 1950s, ‘60s and later — and how they came together to advocate for the patients they cared for. Some of the former employees in the hospital’s more recent years, he said, still get together regularly to catch up and share stories of their time at the facility.

“I was expecting to learn of this tremendously awful institution that was a horror story for Black people in the antebellum South in the wake of the Civil War and that had continued to misdiagnose and otherwise harm the Black community, but that’s not all that I found,” Utsey said. “I mean, that was certainly part of the narrative. But what jumped out at me was the stories of the former employees who transformed the lives of patients because of their own caring and their own focus on the humanity of the patients. Everyone I talked to had their own stories about how they tried to make a difference, how they themselves had to adjust to a situation that was very difficult. But throughout it, they saw the humanity of the people they worked with. And they tried to elevate that as part of their responsibility to the patients.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.