July 5, 2023

History well-spoken: VCU professor Carolyn Eastman to explore speechifying in the Revolutionary Era

Share this story

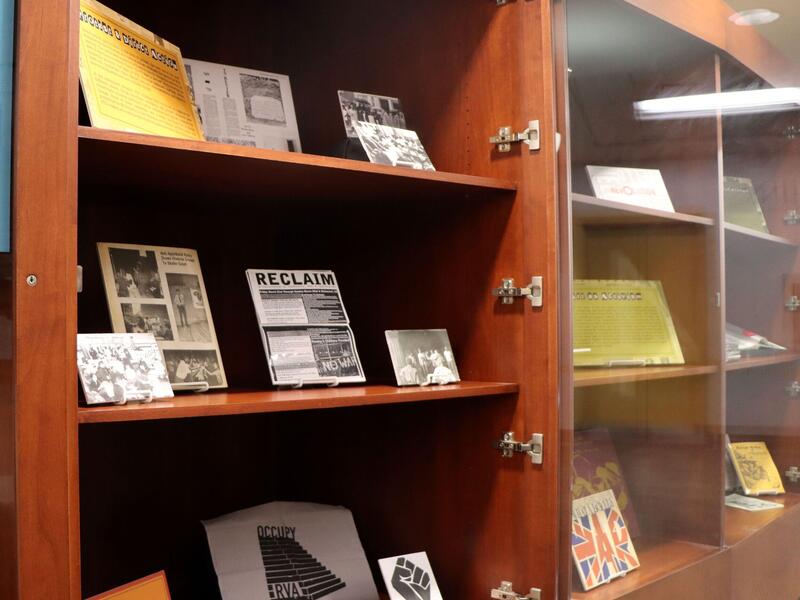

Carolyn Eastman, Ph.D., a professor in Virginia Commonwealth University’s Department of History in the College of Humanities and Sciences, will give a public talk on Thursday, July 20, at Richmond’s historic St. John's Church based on her book “A Nation of Speechifiers: Making an American Public after the Revolution.”

Eastman is a historian of early America with a special interest in 18th- and 19th-century histories of political culture, the media and gender. “A Nation of Speechifiers” examines how ordinary women and men came to understand themselves as “Americans” after the Revolution. By scrutinizing the postwar profusion of print and oral media, the book offers a genealogy of early American identity that integrates politics, manners, gender and race relations.

Eastman’s talk at St. John’s Church, the site of Patrick Henry’s “liberty or death” speech in 1775, will be held Thursday, July 20, from 7 to 8 p.m. Details and tickets are available here.

What will you be discussing in your lecture?

Often when we think of the American Revolution, we think of the importance of newspapers, or books like Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” or documents like the Declaration of Independence. And as much as we know the significance of Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty!” speech in 1775, we don’t tend to think about the importance of oratory more generally during the Revolution. This talk starts with “Give Me Liberty!” and expands outward to talk about the particular value of the spoken word in Richmond, in Virginia and in the Revolutionary era.

In addition to “A Nation of Speechifiers,” you authored “The Strange Genius of Mr. O,” which told the story of orator James Ogilvie, described as one of the first American celebrities. What is it about early American speechifying that you find so interesting?

The fact that we’ve so completely forgotten how important public speech was (and we often overlook how important it continues to be today) means that when I talk about it, you can see people starting to put the pieces together. Studying this subject reminds us how much American history has been punctuated with important speech moments – from Abraham Lincoln’s debates with Stephen Douglas in the 1850s and Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, to Franklin Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s many speeches, including “I Have a Dream.”

What do you think attendees will find most interesting about your talk?

It’s not just about the Great Men (and Women) who delivered those speeches. It’s also about the people in the room listening to those people – and the energy among the audience that the speech created. Studying the history of the spoken word is just as much about the history of democracy in America. As a result, I think attendees will think about Revolutionary America a little bit differently, and think about how the early United States saw oratory as a crucial anchor of democracy going forward.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.