Sept. 19, 2024

English professor’s new book explores opinions – and their various types – in the age of social media

Share this story

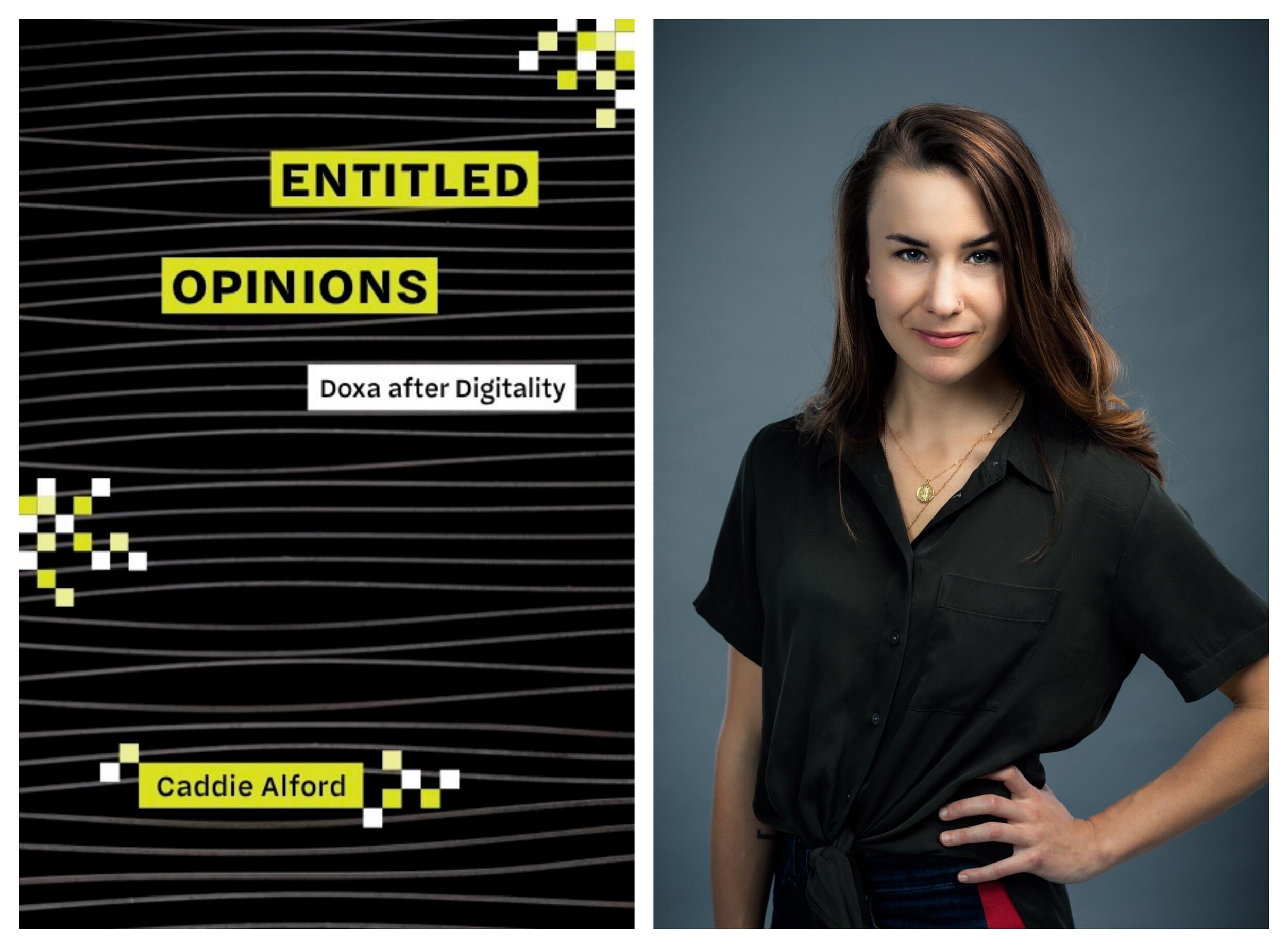

What can ancient Greek philosophy tell us about ourselves in the modern era of social media? Quite a bit, Virginia Commonwealth University’s Caddie Alford says.

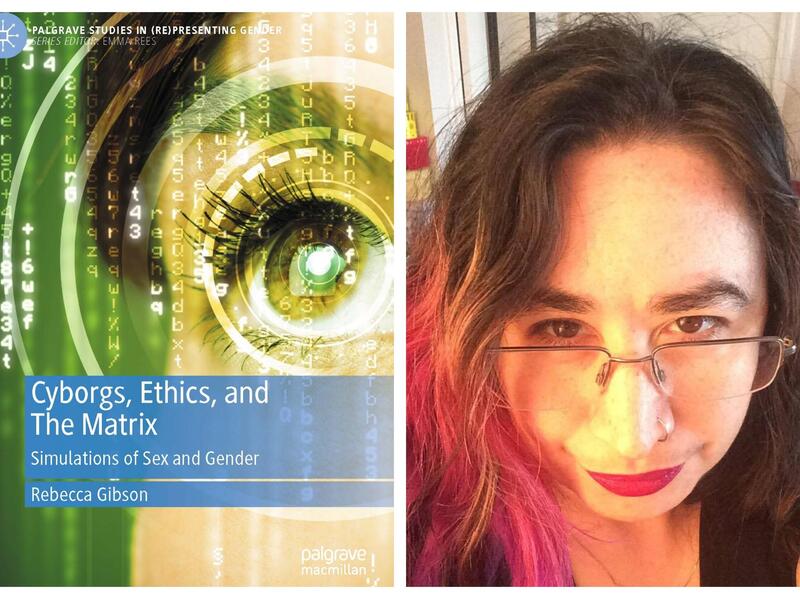

In her new book, “Entitled Opinions: Doxa After Digitality,” Alford, Ph.D., an associate professor of rhetoric and writing in the Department of English in VCU’s College of Humanities and Sciences, explores how opinions inform and are shaped by social media through analyzing algorithms, infrastructure, digital illiteracy, virality and activism.

“Everything that happens on social media has an impact on opinions, and opinions themselves have impacts on the architecture of social media through algorithms and the way they organize people based on their opinions,” Alford said. “How do we relate to each other? What are the mechanisms behind why we click on something, why we bookmark it or why we stop listening to it?”

Alford spoke with VCU News about the ancient Greek concept “doxa” and how social media has changed our understanding of opinions.

First, can you define “doxa” for us?

Doxa is an ancient Greek term that typically gets translated as opinion, but it also meant things like expectation and seemingness. It encompasses a lot of what we take for granted without really even thinking about it.

Everything that motivates you to do what you do in your daily life is probably coming from this well of opinions that make you who you are, based on your experiences, based on where you grew up, based on your race, your gender, your ethnicity – all these components and more. We all have these opinions and taken-for-granted beliefs and values, but it’s not often that we’re forced to interrogate them.

When you take something like doxa and you apply it to opinions, it makes opinions so much more complicated and robust. In fact, my field of rhetorical studies really came into being through conversations distinguishing doxa from facts or knowledge. On the one hand, we had Aristotle and rhetoric’s investment in human messiness. And on the other hand, we had Plato, whose thought was that if we’re going to explore truth and knowledge, we can’t be around anything that fluctuates – and nothing fluctuates more than opinions. Of course, the more you explore “truth” and opinions, the more the two are mutually constitutive.

How does social media affect our understanding of opinions?

Doxa is a perfect thing to consider when we’re thinking about how social media has changed the game in terms of culture and sociality. I really wanted to explore opinions, but social media has warped our relationship to opinions. We don’t even know what opinions are anymore. And we constantly tell each other, “Well, I’m not going to listen to you anymore because everyone’s entitled to their own opinion,” but we don’t even really know what that means.

There’s a lot going into people’s treatment of and understanding of what they read on social media. There’s this psychological phenomenon where anything that feels familiar to us feels more persuasive. So even if you see something once and maybe it’s not true and maybe you even know it’s not true, the fact that you saw it will mean that anything that’s related to that idea in the future won’t necessarily seem immediately true but it’s going to start feeling more and more persuasive.

What is a key notion from “Entitled Opinions” that you want readers to embrace?

One of the huge takeaways from my book is when you take doxa and apply it to opinions, you realize that there’s not just one kind of opinion. There are different types of opinions.

I have different words for this in the book, but it basically boils down to “doxa,” which are opinions that connect you to a wider collective; “endoxa,” which are opinions that are super widely shared and can be community-specific; and “adoxa,” which are opinions that lack substance or status. If I were to say an adoxastic opinion in front of you, you would maybe be shocked because it would be unexpected or not socially reputable.

And these categories are crucial in social media, aren’t they?

What’s interesting about social media is that the way algorithms sort and assign rank to opinions, they therefore find a home and expression for all opinions. Algorithms also organize people based on their opinions. So in some ways, these fringe sorts of opinions are becoming more widely accepted through how the algorithms are assembling us into groups.

Having these categories of opinions gives you a sense of how to evaluate opinions. It gives you a sense of how to work with other people when they don’t necessarily share your ideas or your experiences. We all have to work with opinions, so how do we work with them in smarter ways? And how do we make sure that these platforms are not taking advantage of us more than they already are?

Any final thoughts about opinions in general?

Once you get into opinions, you’ll start to understand that there really is not a strict binary between facts and opinions. It sounds pretty wild to say from a university professor, but it’s true. Opinions are necessary for arguments. They are necessary for research. They’re the reason we do one research project over another. So I would encourage people to think about that tension more critically and how platforms are exploiting that tension as well.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.