Nov. 19, 2024

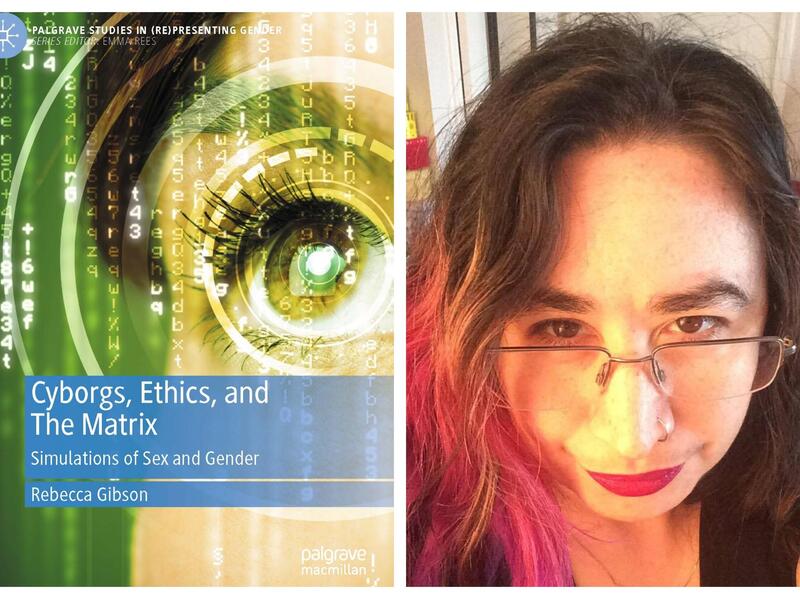

In ‘The Bad Corset,’ VCU author Rebecca Gibson translates – and reframes – a medical text that goes beyond a woman’s waist

Share this story

More than a decade ago, Virginia Commonwealth University author Rebecca Gibson got the wrong book in the mail. It was a mistake that changed the course of her life.

Gibson, Ph.D., a teaching assistant professor of anthropology in VCU’s School of World Studies, had placed an online order for a book about corsetry, the use of undergarments that shape a woman’s body. Instead, she received an unbound, crumbling French medical textbook – “Le Corset” by Ludovic O’Followell, published in 1908 – which had become a defining work on the subject.

“Here was the book that everyone in the discipline of historical fashion culture quoted,” Gibson said. “Here were the radiographs that everyone who talks about corseting has seen – and I had in my hands the actual book, a first edition, of which there are maybe a handful of copies in the world.”

In her new book, “The Bad Corset,” Gibson does more than translate the French doctor’s words. She annotates and critiques O’Followell’s work, exploring contemporary anti-woman bias and challenging widely held conceptions about corsetry’s contribution to disease, disfigurement and disorders of the female body.

Gibson discussed her work, and his, with VCU News.

What inspired you to write “The Bad Corset”?

For a considerable while, “Le Corset” was just a source to me and something to be used in my research to challenge ideas about corseting damage. But then I got to thinking, and more importantly, to actually reading the book.

When you read it, instead of just looking at the images, the entire profile of the book changes. I go into reading everything by thinking about what the author is trying to do: what are their biases, what do they want me to think about this piece, and are there hidden angles to the work that I should take into account when I read it.

And you found biases?

In this case, there certainly are: O’Followell has a relentless anti-woman agenda, and – for over 300 pages – he uses the corset and a surface-level-plausible amount of medical information to repeatedly and viciously slam women, their agentive behaviors and their appearance, particularly if they are atypically feminine or if they are over 30 or no longer of child-bearing age.

This would stand alone as a reason to do this translation, but in addition to that being particularly irritating to my own sensibilities, it is also affecting women and our health care today. The ideas that O’Followell wrote into “Le Corset” can be seen in modern conceptions of women’s pain in general – which is often dismissed as attention-seeking, and specifically in childbirth, where often the needs of the mother are ignored – and the way in which many clinical trials do not take women’s physiology into account.

I have hope that by publishing the first official English language translation of this text, I can help expose the way in which historic ideas influence modern-day medical misogyny.

Let’s go back to the era of “Le Corset.” What should we know?

When I started working on this book, I wanted to highlight the need for seeing historical documents as a product of their own time, but also as highly flawed and in need of reinterpretation. 1908 was a year that came directly in the middle of a massive amount of cultural change. Regardless of where one was in the world, ideas about medicine, women and human rights were in flux.

For my three areas of concentration – France, the U.K. and the U.S. – this was a period of time where, for the first time, women were being seen as medical subjects separate from the men in their lives. It was during this time that we saw a strong push for voting rights, financial and property rights, and the right to bodily autonomy, all of which would take further decades to come to fruition.

Through this lens, I wrote the annotations, as well as the introduction and afterword, to “The Bad Corset” to provide a better and more holistic context to the world in which O’Followell wrote “Le Corset.”

What is the most common perception – or misperception – that you address in “The Bad Corset”?

The biggest assertion is the effect of corsetry on the rib cage. This is the area of biological anthropology that I wrote my dissertation on, and I later turned my dissertation into my second book publication, “The Corseted Skeleton: A Bioarchaeology of Binding.”

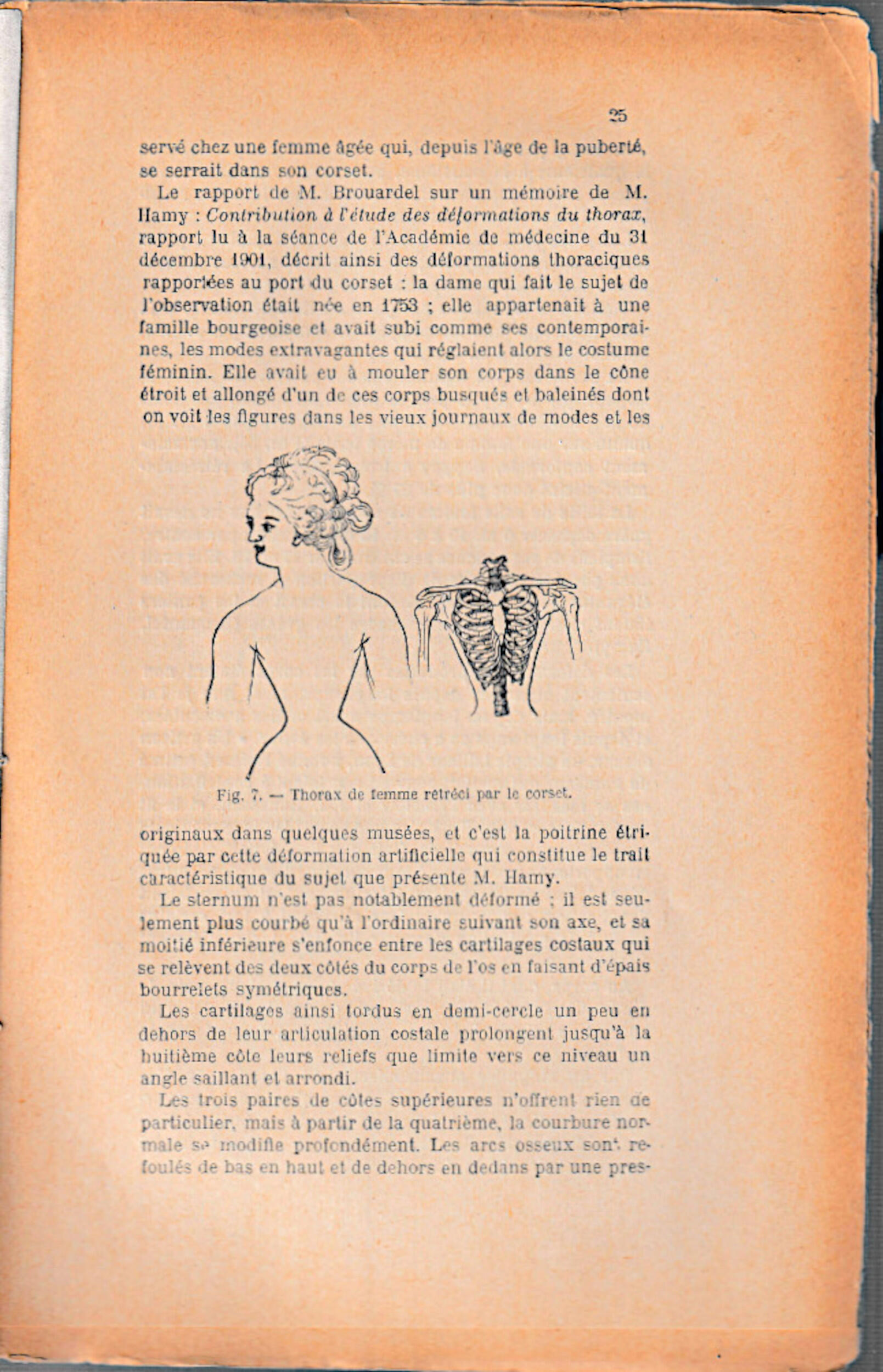

Corseting does affect the ribs, but popular understanding of how, why and how drastically has largely ignored the science of skeletal change and focused on the sensational. Enter the illustrations from “Le Corset.” The book’s influence on popular knowledge can be seen from the most commonly seen and discussed images that come from it: a line drawing of a distorted rib cage, and radiographs that show an altered rib cage.

However, those do not actually prove anything. Anyone can draw something – that doesn’t make it real or accurate, and the radiographic images were falsified to make O’Followell’s point, subjected to the 1908 equivalent of photoshopping – creating composite images and distortions of reality. And most of them were not created by x-raying living people.

What are other misperceptions?

Secondarily is the misattribution of various ills, injuries and maladies to the corset. O’Followell’s first chapter lists 46 individual “symptoms” of corseting damage, and across the next 306 pages, he dedicates chapters to each organ system of the body, showing what abdominal and thoracic compression “does” to the system.

Yet much of what he writes ignores medical knowledge that was available at the time of his writing, and he refuses to consider any other causes than the corset. O’Followell eschews such things as differential diagnoses, self-reports from his patients, commonly understood correlations – for example, the fact that even in 1908 it was known that uterine prolapse is highly correlated with multiparity, or having many children – and any type of relevant understanding of art and art history, as he repeatedly and incorrectly compares women’s bodies to their counterparts in historical fine art.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.